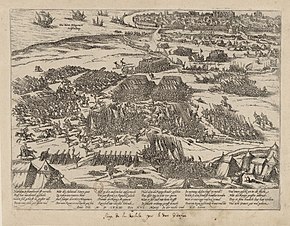

St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in the provinces

These events severely impacted Huguenot communities outside their strongholds in Southern France; the deaths combined with fear and distrust of Catholic intentions resulted in a large wave of conversions, while many others went into exile.

However lack of direct evidence for this means historians now view the massacres as driven by zealous Catholics within provincial administrations or the court, who either knowingly or unknowingly deceived themselves as to the King's wishes regarding the fate of the Huguenots.

[1] Second; 1567–1568Saint-Denis; Chartres Third; 1568–1570Jarnac; La Roche-l'Abeille; Poitiers; Orthez; Moncontour; Saint-Jean d'Angély; Arney-le-Duc Fourth; 1572–1573Mons; Sommières; Sancerre; La Rochelle Fifth; 1574–1576Dormans Sixth; 1577La Charité-sur-Loire; Issoire; Brouage Seventh; 1580La Fère War of the Three Henrys (1585–1589)Coutras; Vimory; Auneau; Day of the Barricades Succession of Henry IV of France (1589–1594)Arques; Ivry; Paris; Château-Laudran; Rouen; Caudebec; Craon; 1st Luxembourg; Blaye; Morlaix; Fort Crozon Franco-Spanish War (1595–1598)2nd Luxembourg; Fontaine-Française; Ham; Le Catelet; Doullens; Cambrai; Calais; La Fère; Ardres; Amiens For the Protestant polemicists of the sixteenth century onwards, there was no question that the massacres had been personally directed by Charles IX and his secret council, and this was largely the position adopted by historians into the nineteenth century.

[3] They discovered Charles despatched two sets of letters to the provinces, on 24 and 28 August respectively, in which he ordered recipients to comply with the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and protect local Protestants from violence.

[4] Although Calvinist historians were aware of these instructions, they suggested they were simply a cunning charade to disguise his true orders to his governors, which would be delivered orally.

[7] His vacillations did not end there however; when Vaucluse approached him at a public banquet and attempted to clarify whether his orders included killing, Charles asked him to return the following morning to his chambers, where he told him in private that Huguenots in Provence should be spared.

[8] This suggests those who wanted to extend the killings into the provinces included the hardline Catholic extremist nobles who were present at the banquet and whom Charles was uncomfortable at speaking against in public.

[8] In the days following the massacre, many of these nobles would write back to their respective provinces, insinuating that it was the kings wish that the Huguenots be eliminated throughout France.

[9][10][11] Many other hardline local representatives of towns, who had been to Paris on official business, likewise reported back that the king desired a massacre, as happened with Belin in Troyes and with Rubys in Lyon.

[18] Toulouse and Troyes had both seen failed attempts at takeovers, the former a very bloody one, and La Charité had been granted to the Huguenots as a security town at the end of the third civil war.

[18] Saumur and Angers are exceptions to this pattern of violent civil war history, yet their massacres are also different in character to many of the others, largely the work of zealous officials with little popular involvement.

In towns such as La Rochelle, Montauban and Nîmes the Protestant ascendency was such that they could be little threatened by their Catholic population, and with their political power, could close the gates to any external threat.

[23] Finally cities such as Reims and Dijon had reached such a dominant level of Catholicism, that their small Protestant populations were too weak and cowed to pose enough of a threat to be worth massacring.

[23] The massacres were generally organised in time, with a few notable exceptions, by their proximity to Paris, as many of them bloomed during the initial chaos when the king's intentions weren't clear.

[26] The next day Casset turned to liquidate the arrested Protestants who were filling the prisons, a list was drawn up of 200 names for execution, largely composed of merchants artisans and judicial officials.

[37] Lyons received news of events in Paris first on 27 August when information about the attempt on Coligny's life arrived from the kings letter.

[39] The next day a letter from the king arrived, delivered by du Peyrat urging governor Mandelot to keep the peace in the town but also containing secret instructions, to arrest and seize the property of the Huguenots.

[40] Later in the evening the mob advanced on the Roanne and the 70 Protestants inside were killed, Calm would not be restored until 2 September, by which time between 500 and 1000 Huguenots were dead.

[47] To do the work they employ prison guards, the executioner having refused to be involved, several other Huguenots being killed in the streets by angry Catholics.

[49] Rouen receives news of what had happened in Paris around the same time, in a letter to the governor Carrouges from the King, which bemoaned the lamentable sedition that had befallen the capital.

[51] This uneasy peace was broken on 17 September when, a mob, under the leadership of Laurent de Maromme who had previously been involved in the massacre of Bondeville and the curate of the St Pierre church Montereul seized the city.

[52][53] They locked the gates and then first stormed the various prisons where the Huguenots were being kept, killing them all, and after having completed that devolved into breaking into houses searching for stragglers and looting for the next 4 days before order was restored.

[55] Yet this was accompanied by governor Montferrands order, forbidding Huguenot worship which had been permitted some distance away from the city by the Peace of Saint Germain in 1570.

[60] There would also be violent disturbances in several other smaller urban centres, including Albi, Garches, Rabastens, Romans, Valence, Drôme and Orange.

[60] As Vaucluse was approaching Paris he crossed paths with de la Molle going the other way, with alleged confirmed orders to massacre the Huguenots of Provence.

[60] Vaucluse hurried back to Provence, overtaking de la Molle on route, and thus aided the averting of the massacre in Aix.

[64] In Troyes we see a similar wave, with so many seeking to reconcile with the Catholic church that the town had to hire a special priest to hear the confessions.

[65] This trend of abjurations and exile occurred even in towns in the north that had experienced no massacre, Protestants ill inclined to trust any royal guarantee of safety going forward.

[63] A general feeling of defeatist despair overcame the northern Protestants, accompanied with soul searching as to how their god could have allowed this to happen, with some concluding it was punishment for their sins.

[67] The king, despite his opposition to the massacres, decided not to let a good opportunity go to waste, and in early 1573 he banned Protestants from serving in royal office.