St John Passion structure

The structure of the St John Passion (German: Johannes-Passion), BWV 245, a sacred oratorio by Johann Sebastian Bach first performed in Leipzig on Good Friday 1724, is "carefully designed with a great deal of musico-theological intent".

The "immediate, dramatic quality" of the "kind of musical equivalent of the Passion Play" relies on the setting of the interaction between the historical persons (Jesus, Pilate, Peter, Maid, Servant) and the crowd ("soldiers, priests, and populace").

It was compiled by an unknown author, who partly used existing text: from the Brockes Passion (Der für die Sünde der Welt Gemarterte und Sterbende Jesus, aus den IV Evangelisten, Hamburg, 1712 and 1715) by Barthold Heinrich Brockes, he copied the text for movements 7, 19, 20, 24, 32, 34, 35 (partly) and 39; he found movement 13 in Christian Weise's Der Grünen Jugend Nothwendige Gedanken (Leipzig, 1675) and took from Postel's Johannes-Passion (c. 1700) movements 19 (partly), 22 and 30.

Again, in a repetition of similar musical material, a preceding turba choir explains the law, while a corresponding movement reminds Pilate of the Emperor whose authority is challenged by someone calling himself a king.

[9] Bach led the first performance on 7 April 1724[10] at the Nikolaikirche (St. Nicholas)[11] as part of a Vesper service for Good Friday.

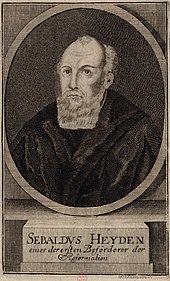

In version 2, Bach opened with a chorale fantasia on "O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß" (O man, bewail thy sins so great), the first stanza of a 1525 hymn by Sebald Heyden,[8] a movement which he ultimately used to conclude Part I of his St Matthew Passion, returning to the previous chorus Herr, unser Herrscher in later versions of the St John Passion.

[8] Bach took this movement from his cantata Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn, BWV 23, which had been an audition piece for his post in Leipzig.

As Christoph Wolff observes: "The fragmentary revised score constitutes an extensive stylistic overhaul with painstaking improvements to the part-writing and a partial restructuring of the instrumentation; particular attention was paid to the word-setting in the recitatives and the continuo accompaniment.

[14] Wolff writes: "Bach experimented with the St John Passion as he did with no other large-scale composition",[11] possible by the work's structure with the Gospel text as its backbone and interspersed features that could be exchanged.

"O große Lieb, o Lieb ohn alle Maße" (O mighty love, O love beyond all measure)[8] is stanza 7 of Johann Heermann's 1630 hymn "Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen",[16] part of a movement to make German a literary language by imposing strict rules of metre and hymn; the form is that of a Sapphic stanza with the characteristically short last forth line which here literally is a punch line, hitting home: "Und du mußt leiden" (And you must suffer).

[8] The hymn is based on a passion meditation which was attributed to the church father St Augustine (Meditationes Divi Augustini, chapter VII) – another nod to classical learning but with all the emotionally charged medieval rhetoric of Anselm of Canterbury or Bernard of Clairvaux.

The text addresses the crucified Christ pondering on the bodily signs of the passion but even more on the significance of this display of suffering.

This verse breaks into the exclamation of wonder: a highly emotionally charged start the triple ‘o’ in the first line and the neologism of the ‘Marterstraße’ in the second which Bach makes audible in the chromatically discordant setting.

It imagines Christ being physically pushed by Love personified on the road of suffering while the singer lives with Mrs World in sinful pleasure – a combination of the medieval concept of the “Crucifixion by the virtues” with the pilgrim’s progress idea of encountering virtues and vices on the way.

[8][20] The sixth chorale, movement 17, comments in two more stanzas from "Herzliebster Jesu" (3), after Jesus addresses the different people of his kingdom.

Stanza 8, "Ach großer König, groß zu allen Zeiten" (Ah King so mighty, mighty in all ages)[8] reflects the need for thanksgiving and stanza 9 the inability to grasp it, "Ich kanns mit meinen Sinnen nicht erreichen" (I cannot with my reason ever fathom).

[8][23][24] The eighth chorale, movement 26, ends the scene of the court hearing, after Pilate refuses to change the inscription.

"In meines Herzens Grunde" (Within my heart's foundation)[8] is stanza 3 of Valerius Herberger's 1613 hymn "Valet will ich dir geben".

"Jesu, der du warest tot, lebest nun ohn' Ende" (Jesus, you who suffered death, now live forever)[8] is the final stanza of Stockmann's hymn (14).

However, he decided to compose a true St John Passion, and thus eliminated the material inserted from the Gospel of Matthew.

On 17 March 1739, while still working on this revision, Bach was informed that the performance of the Passion setting could not go ahead without official permission, thus (most likely) effectively halting any plans for that year.