St Mary's Church, Southampton

[7] The foundation of the first church on the site is believed to coincide with the visit of Saint Birinus to the port town of Hamwic in circa 634, on his mission to reconvert England to Christianity.

This first church was a small, Saxon building that nevertheless controlled a large swathe of the town, from the River Itchen to what is now present-day Northam.

The early history of this church is not well known, but it is believed by historians that during the reign of King Canute (1016–1035), the ancient town of Hamwic was moved to sit on the site of modern-day Southampton, close to the confluence of the Test and Itchen.

[4][8] The story of the rebuilding of the church in the 12th century comes from Leland's chronicle of 1546, where he explains that its reconstruction was ordered by Queen Matilda, wife of Henry I, owing to its poor condition.

The dispute was settled by the Bishop of Winchester, who sent his representative, Adam de Hales, to conduct an enquiry on the status of the various churches in the town.

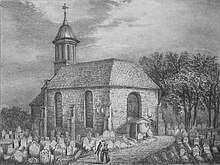

[4] A description of the church appeared in Picture of Southampton in 1850:[10] It has been recently enlarged by the addition of two wings; and is now in tolerable repair, but more remarkable for its bold defiance of all architectural propriety, than for any other characteristic: tall clustered columns being carried from the floor to support a horizontal beam or entablature close to the ceiling, whilst plain round windows contrast the pointed arch of the ancient chancel.

This, combined with the rapidly expanding population, prompted the Bishop of Winchester, Samuel Wilberforce, whose son was also the rector,[11] to strongly campaign for its replacement.

Consequently, William Wilberforce, his son, instructed the eminent architect of the age, George Edmund Street, to survey the church.

The church would not be fully completed for another 30 years, when under the auspices of the rector, Canon Lovett, the tower and spire were constructed, to Street's design, from 1912 to 1914.

The church had an aisled nave, north and south transepts, and chancel, with a high southwest tower, topped with a spire.

St Mary's Church was hit several times by incendiaries, which started a fire that consumed most of the structure, despite the efforts of the rector and his team.

When morning broke, the church was virtually ruinous, save for the tower, spire, and conical baptistery, which survived, albeit gutted internally.

An offer of a new site to rebuild the church in East Park Terrace by the council in 1946 was turned down, and the diocese had reservations about funding such a large building when much of the country was still under rationing.

[13] The internal alterations included the installation of a kitchen and servery, new lighting and sound systems, refurbishment of toilets, and a stage in the centre of the church.

As part of the modernisation, a church plant took place, with Holy Trinity Brompton installing a new vicar; the churchmanship also changed to Charismatic Evangelical.

The dominant feature of the exterior is the massive tower and spire, which reach a height of 200 feet (61 m),[17] making St Mary's the tallest church in Hampshire.

Whilst Nikolaus Pevsner was critical of the body of the church following its rebuilding, he praised the tower and the spire, making a "splendid composition", calling it "one of the finest Victorian steeples in England".

The third, upper, stage contains pairs of massive louvred bell openings, spanning the entire height and width of the walls.

[16] Unlike the exterior, which retains several features of Street's church, the interior mostly reflects Craze's post-war rebuilding.

The largest of these is the west window, containing seven lights in the Decorated Gothic style, depicting Christ in Majesty with many background scenes.

The large, five-light window in the Seafarers' Chapel is Decorated Gothic in style and contains glass by Smith again, this time depicting Christ over the sea, looking down on modern ships.

The window, originally designed as part of the Worshipful Company of Glaziers’ Stevens Competition, was created by Louise Hemmings of Ark Stained Glass.

Made using traditional stained glass techniques, the window depicts an angel rising from the waters holding a scroll that says "the crew".

The organ is amongst the largest and finest of any church on the South Coast of England, comprising 3,383 pipes controlled by 61 speaking stops over three manuals plus pedalboard.

When the fifth incarnation of the building was under construction from 1878 to 1884, only the lowest stage of the tower was completed, as far as the stone vault visible from the church, too low to contain any bells.

Though over £2,500 had been raised so that the tower and spire would be completed,[25] it required a donation of almost £1,000 by a local resident, Mary Ann Wingrove, so that a peal of bells could be provided.

The first full peal on the bells was on 8 January 1916, comprising 5,040 changes of Grandsire Triples, rung in 3 hours and 13 minutes, to commemorate the fallen of the First World War.

During an inspection in March 1941 by Taylor's foundry, it was found that the fifth, eighth, and ninth bells had gaping cracks and the seventh had lost its resonance.

[26] It had been hoped to reuse the original frame for the new bells, but inspections in 1946 showed fire damage had weakened it, so it was removed and replaced, except for the 1934 extension, which was left in-situ.

From 1887 to 1896, the church was the club's landlord, being the owners of their first permanent home at the Antelope Ground, situated at the northern end of St. Mary's Road.