St Peter's Collegiate Church

Characterised by absenteeism and corruption through most of its history, the college was involved in constant political and legal strife, and it was dissolved and restored a total of three times, before a fourth and final dissolution in 1846-8 cleared the way for St Peter's to become an active urban parish church and the focus of civic pride.

Some of the places named are fairly easy to recognise from their modern or medieval forms: Arley, Bilston, Willenhall, Wednesfield, Pelsall, Ogley Hay, Hilton, Hatherton, Kinvaston, Featherstone.

[13] Wulfgeat was an important adviser to Ethelred, a king who proverbially, as the Unready or Redeless, did not accept good advice: he fell into disgrace[14] and Wulfrun's grants were partly to make amends for his perceived injustices.

[22] Richard A. Fletcher noted that in this period of renewed Viking activity there were numerous "communities of clergy at which reformers looked askance but which very probably made a significant if unobtrusive contribution to the Christianization of Anglo-Scandinavian England.

The forged letter of Edward the Confessor is meant to point to just such a close relationship, but we know it dates from a century later, after the church had Wolverhampton had passed through a series of difficulties which it probably wanted to resolve permanently.

Sciatis me dedisse Sampsoni capellano meo ecclesiam Sancte Marie de Wolvrenehamptonia, cum terra et omnibus aliis rebus et consuetudinibus, sicut melius predicta ecclesia habuit tempore regis Edwardi.

He had been tutor to William II of Sicily, one of the most cultivated rulers of his time, and Henry had brought him into his circle of close supporters when he was under extreme pressure because of the murder of Thomas Becket and ruptures in the royal family.

[53] The earliest extant evidence of any interest Wolverhampton is a letter he wrote to the Chancellor, William Longchamp, to denounce the “tyranny of the Sheriff of Stafford”[54] who was, he complained, trampling on the church's ancient privileges and oppressing the townspeople.

[57] With the assent of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the king, a Cistercian monastery could be established, as the area abounded in the woods, meadows and waters[58] needed by this ascetic French order dedicated to a radical and literal interpretation of the Benedictine Rule.

[69] John had changed his mind completely and on 5 August 1205, only three weeks after the archbishop's death, he appointed a replacement dean of Wolverhampton: Henry, the son of his Chief Justiciar, Geoffrey Fitz Peter, 1st Earl of Essex.

"[76] The prohibition cited a Papal rescript, issued at Lyon in 1245, that guaranteed the independence of royal chapels, which it characterised as ecclesiae Romanae immediate subjecta, directly subordinate to the Roman Church.

In 1258 Erdington secured for the deanery the lucrative right to hold a "weekly market on Wednesaday at Wolverhampton, co. Stafford, and of a yearly fair there on the vigil and Feast of Saints Peter and Paul and the six days following,"[82] both of which took place thereafter at the foot of the church steps.

Erdington conceded various useful pieces of land, including 20 acres at Wolverhampton and roadside verges on the route through Ettingshall and Sedgley, in return for an annual rent of eight pounds of wax[84] – useful to the church with its constant need for candles.

[88] The next dean was Theodosius de Camilla, an Italian cleric related to the powerful Fieschi family[89] of Genoa, and a cousin of Pope Adrian V.[90] He was appointed on 10 January 1269,[91] following Erdington's death.

Around 1274, finding that tenants at Bilbrook had failed to pay their tallage or hand over their best pigs in return for pannage in the woods, the deanery simply seized their cattle on the road[100] and sat out their attempt to gain restitution.

"[129] An inspeximus of 1376 revealed another of John's land sales in the area, and one dating from the time of Theodosius, but confirms both, "notwithstanding that the said plots were of the foundation of the said church, which is now called the king's free chapel of Wolvernehampton.

[131] A further commission in March 1340 added an investigation of the books, vestments and ornaments,[132] while in the following year the king opined that Ellis had "wasted the goods and possessions of the deanery, whereby the divine worship and works of piety of old established there have been withdrawn.

A vast quantity of expensive cutlery, silverware, tableware, linen, precious stones, horses, livestock, even a relic of the True Cross, had been dispersed among friends and retainers or stolen from Hugh's custody.

[179] Moreover, the canons had farmed out most of their holdings on perpetual leases, at fixed and very low rents, to the Leveson and Brooke families—allegedly in the hope of recovering them later and protecting the college's investments, but probably to make a quick gain before dissolution.

The deans and most of the canons stayed away, failing to attend even the quarterly chapter meetings and paying scant wages to deacons, and in some cases unordained readers, to perform their functions at St Peter's.

[188] Several of his contemporaries at Wolverhampton were also ambitious, rising clerics, like the consecutive Hatherton prebendaries Godfrey Goodman, a Catholic sympathiser and future bishop, and Cesar Callendrine,[189] a German Calvinist minister who long headed the Dutch Reformed Church in London.

Hall found St Peter's under the thumb of Walter Leveson: "the freedom of a goodly Church, consisting of a Dean and eight prebendaries competently endowed, and many thousand souls lamentably swallowed up by wilful recusants, in a pretended fee-farm for ever."

The Clergy of the Church of England database, if the identification is correct, records his appointment in 1640 as vicar of Melbourne, where the advowson was held by John Coke,[202] and in 1643 as rector of Rugby, where the patron was Humphrey Burnaby.

And that you take speciall notice of one Mr Lee, a Prebend there who hath been the Author of much disorder thereabouts, And if you can fasten upon any thing, whereby he may justly be censured, pray see it be done, and home, or bring him to the High Commission Court to answer it there, &c. But HOWEVER let him not obtain any License to Preach any Lecture there, or in another Exempt place hard by at Tetenshall, whither those of Wolverhampton do now run after him, out of their Parish; Note.

As also that in another place thereabouts they caused a Bell-man in open Market to make Proclamation for a Sermon...[205]At his trial in July 1644 Laud argued that he ordered proceedings against Lee only "If there were found against him that which might justly be Censured,"[206] a wording that differs significantly from Prynne's version.

However, Shaw points out this Ordinance for sequestring notorious Delinquents Estates,[208] which did name 14 bishops and refer to deans and prebends, was not a law against Church lands but an expedient for raising funds for the Parliamentary army.

In September 1653 Robert Leveson alleged that his father Thomas, who held the tithes of Upper Penn as well as St Peter's and 13 other churches, had already settled the estates on himself as early as 1640, before the civil war began.

However, the curates initially performed their duties very much better than earlier sacrists and things were improved further by the building of a new chapel of ease in the town: St George's, another Neo-Classical structure, completed in 1830 to a design by James Morgan.

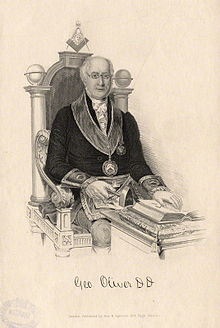

[233] These involved clashes in the pulpit and the public prints with the clergy of St George's over burial and other fees, with Oliver countering every argument of his opponents with a new pamphlet, invariably headed a Candid Reply.

The chancel was reconstructed in 1682 following considerable damage caused to the original medieval one during the Civil War, and it was again completely rebuilt in 1867 as part of the extensive restoration of the Church under architect Ewan Christian.