Homotopy groups of spheres

The n-sphere may be defined geometrically as the set of points in a Euclidean space of dimension n + 1 located at a unit distance from the origin.

The problem of determining πi(Sn) falls into three regimes, depending on whether i is less than, equal to, or greater than n: The question of computing the homotopy group πn+k(Sn) for positive k turned out to be a central question in algebraic topology that has contributed to development of many of its fundamental techniques and has served as a stimulating focus of research.

Most modern computations use spectral sequences, a technique first applied to homotopy groups of spheres by Jean-Pierre Serre.

The study of homotopy groups of spheres builds on a great deal of background material, here briefly reviewed.

The distinguishing feature of a topological space is its continuity structure, formalized in terms of open sets or neighborhoods.

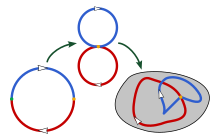

An important practical example is the residue theorem of complex analysis, where "closed curves" are continuous maps from the circle into the complex plane, and where two closed curves produce the same integral result if they are homotopic in the topological space consisting of the plane minus the points of singularity.

[8] More generally, the i-th homotopy group, πi(X) begins with the pointed i-sphere (Si, s), and otherwise follows the same procedure.

In particular, if the map is a continuous bijection (a homeomorphism), so that the two spaces have the same topology, then their i-th homotopy groups are isomorphic for all i.

[citation needed] The low-dimensional examples of homotopy groups of spheres provide a sense of the subject, because these special cases can be visualized in ordinary 3-dimensional space.

Unfortunately, the only example which can easily be visualized is not interesting: there are no nontrivial mappings from the ordinary sphere to the circle.

[16] A more rigorous approach was adopted by Henri Poincaré in his 1895 set of papers Analysis situs where the related concepts of homology and the fundamental group were also introduced.

[19] An important method for calculating the various groups is the concept of stable algebraic topology, which finds properties that are independent of the dimensions.

Jean-Pierre Serre used spectral sequences to show that most of these groups are finite, the exceptions being πn(Sn) and π4n−1(S2n).

Others who worked in this area included José Adem, Hiroshi Toda, Frank Adams, J. Peter May, Mark Mahowald, Daniel Isaksen, Guozhen Wang, and Zhouli Xu.

It follows from the definition of homotopy groups that the identity map and its multiples are elements of πn(Sn).

As noted already, π1(S1) = Z, and π2(S2) contains a copy of Z generated by the identity map, so the fact that there is a surjective homomorphism from π1(S1) to π2(S2) implies that π2(S2) = Z.

[citation needed] The following table gives an idea of the complexity of the higher homotopy groups even for spheres of dimension 8 or less.

[21] Beyond the first row, the higher homotopy groups (i > n) appear to be chaotic, but in fact there are many patterns, some obvious and some very subtle.

, where the bundle projection is a double covering), there are generalized Hopf fibrations constructed using pairs of quaternions or octonions instead of complex numbers.

[citation needed] Homotopy groups of spheres are closely related to cobordism classes of manifolds.

The projection of the Hopf fibration S3 → S2 represents a generator of π3(S2) = Ωframed1(S3) = Z which corresponds to the framed 1-dimensional submanifold of S3 defined by the standard embedding S1 ⊂ S3 with a nonstandard trivialization of the normal 2-plane bundle.

Until the advent of more sophisticated algebraic methods in the early 1950s (Serre) the Pontrjagin isomorphism was the main tool for computing the homotopy groups of spheres.

[26] This is in some sense the best possible result, as these groups are known to have elements of this order for some values of k.[27] Furthermore, the stable range can be extended in this case: if n is odd then the double suspension from πk(Sn) to πk+2(Sn+2) is an isomorphism of p-components if k < p(n + 1) − 3, and an epimorphism if equality holds.

[29] This exact sequence is similar to the ones coming from the Hopf fibration; the difference is that it works for all even-dimensional spheres, albeit at the expense of ignoring 2-torsion.

For example, if k < 2p(p − 1) − 2 for a prime p then the p-primary component of the stable homotopy group πSk vanishes unless k + 1 is divisible by 2(p − 1), in which case it is cyclic of order p.[30] An important subgroup of πn+k(Sn), for k ≥ 2, is the image of the J-homomorphism J : πk(SO(n)) → πn+k(Sn), where SO(n) denotes the special orthogonal group.

This period 8 pattern is known as Bott periodicity, and it is reflected in the stable homotopy groups of spheres via the image of the J-homomorphism which is: This last case accounts for the elements of unusually large finite order in πn+k(Sn) for such values of k. For example, the stable groups πn+11(Sn) have a cyclic subgroup of order 504, the denominator of B6/12 = 1/504.

Roughly speaking, the image of the J-homomorphism is the subgroup of "well understood" or "easy" elements of the stable homotopy groups.

The quotient of πSn by the image of the J-homomorphism is considered to be the "hard" part of the stable homotopy groups of spheres (Adams 1966).

Tables of homotopy groups of spheres sometimes omit the "easy" part im(J) to save space.

[citation needed] The direct sum of the stable homotopy groups of spheres is a supercommutative graded ring, where multiplication is given by composition of representing maps, and any element of non-zero degree is nilpotent;[32] the nilpotence theorem on complex cobordism implies Nishida's theorem.