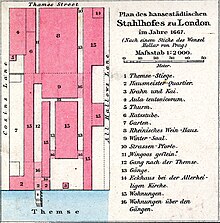

Steelyard

[2]: 96 In Charles Kingsford's commentary on John Stow's A Survey of London (1598 edition) the Middle Low German name Stâlhof is the older usage, appearing as early as 1320.

In 1394 an English merchant writing from Danzig has: In civitate Londonia[...]in Curia Calibis: "In the city of London[...]at the court of steel" (chalybs).

In 1988 remains of the former Hanseatic kontor, once the largest medieval trading complex in Britain, were uncovered by archaeologists during maintenance work on Cannon Street Station.

Merchants from Cologne bought a building at the corner of Thames Street and Cousin Lane in the 1170s, though they seem to have used it as early as 1157, and it became known as the "Germans' Guildhall" (Gildahalda teutonicorum).

[2]: 96 [3] Henry II of England granted very extensive privileges to traders from Cologne in 1175/76 in an attempt to limit the power of Flemish merchants who then controlled the English wool trade.

[7]: 35–36 They are alluded to in the De itinere navali, an account of crusaders from Lübeck for whom the kontor arranged the purchase of a replacement cog in the summer of 1189.

[7]: 61 Low German traders from the area around the Baltic Sea appeared in England too around this time, but they directed their trade more at English towns up north.

They took over the hegemony in the trade with England from the Flemings later in the century and even began to get involved in the export of English wool to Flanders.

[7]: 58–59 The settlement was only later made official as the Steelyard and confirmed in tax and customs concessions granted by Edward I, in a Carta Mercatoria ("merchant charter") of 1303.

A trade conflict began in 1385 when an English privateer fleet seized a number of Hanseatic ships near Bruges in the Zwin.

But when a new grand master cancelled the treaty of Marienburg in 1398 after Prussian towns complained, Henry IV did not retaliate and instead reconfirmed the Hanseatic privileges.

The Teutonic grandmaster did not ratify the treaty, pressed by Danzig, but England still enforced it despite unfulfilled demands for equal privileges for English traders in 1442 and 1446.

Lübeck instructed German traders to leave England in 1450 and blocked English trade through the Øresund in 1452 by an agreement with Christian I of Denmark.

England was weakened after the Hundred Years' War and briefly restored the Hanseatic privileges, though another salt fleet from Lübeck was taken in 1458.

[9]: 96–97 Edward IV held the Hanseatic League responsible, when English ships were attacked in the Øresund by Danes in 1468, and German merchants in London were arrested and convicted by the crown council.

Edward IV was helped by Hanseatic ships in his landing in May to retake power, but he reaffirmed Cologne's exclusive privileges in July.

[2]: 97 [12] In exchange for the privileges the German merchants had to maintain Bishopsgate, one of the originally seven gates of the city, from where the roads led to their interests in Boston and Lynn.

[10]: 106 Other Hanse towns resented the success of the Merchant Adventurers and wanted to secure the old favorable trade privileges that England suspended years ago.

Consulates of the Hanseatic cities provided indirect communication between Northern Germany and Whitehall during the European blockade of the Napoleonic wars.

Patrick Colquhoun was appointed as Resident Minister and Consul general by the Hanseatic cities of Hamburg in 1804 and by Bremen and Lübeck shortly after as the successor of Henry Heymann, who was also Stahlhofmeister, "master of the Steelyard".

[2]: 91 Security was the primary reason for establishing kontors, but they were also important for inspecting the quality of trade goods and diplomacy with local and regional authorities.

They had however many ties with Londoners, for example Englishmen acted as executors for Hansards, and merchants rented rooms from the English, so they were not nearly as segregated as at Novgorod's Peterhof.

[citation needed] In effect, the Steelyard was a separate and independent community, governed by the codes of the Hanseatic League, and enforced by the merchants' native cities.

[19] The Steelyard had its own statutes, like any kontor, written in Middle Low German, the main language of the Hanseatic merchants.

Trade in London was not controlled by the Hansards, and they met traders from various places in Europe, offering the availability of exotic goods but showing also new ideas and customs.