Cosmic distance ladder

The ladder analogy arises because no single technique can measure distances at all ranges encountered in astronomy.

Early fundamental distances—such as the radii of the earth, moon and sun, and the distances between them—were well estimated with very low technology by the ancient Greeks.

Astronomers usually express distances in units of parsecs (parallax arcseconds); light-years are used in popular media.

The Hubble Space Telescope's Wide Field Camera 3 has the potential to provide a precision of 20 to 40 microarcseconds, enabling reliable distance measurements up to 5,000 parsecs (16,000 ly) for small numbers of stars.

For a group of stars with the same spectral class and a similar magnitude range, a mean parallax can be derived from statistical analysis of the proper motions relative to their radial velocities.

However, secular parallax introduces a higher level of uncertainty because the relative velocity of observed stars is an additional unknown.

For example, all observations seem to indicate that Type Ia supernovae that are of known distance have the same brightness, corrected by the shape of the light curve.

As a result, the population II stars were actually much brighter than believed, and when corrected, this had the effect of doubling the estimates of distances to the globular clusters, the nearby galaxies, and the diameter of the Milky Way.

By observing the waveform, the chirp mass can be computed and thence the power (rate of energy emission) of the gravitational waves.

Less easy to discern and control for is the effect of weak lensing, where the signal's path through space is affected by many small magnification and demagnification events.

It is difficult for detector networks to measure the polarization of a signal accurately if the binary system is observed nearly face-on.

Unfortunately, binaries radiate most strongly perpendicular to the orbital plane, so face-on signals are intrinsically stronger and the most commonly observed.

If the binary consists of a pair of neutron stars, their merger will be accompanied by a kilonova/hypernova explosion that may allow the position to be accurately identified by electromagnetic telescopes.

In the early universe (before recombination) the baryons and photons scatter off each other, and form a tightly coupled fluid that can support sound waves.

The method requires an extensive galaxy survey in order to make this scale visible, but has been measured with percent-level precision (see baryon acoustic oscillations).

A comparison of this value with the apparent magnitude allows the approximate distance to be determined, after correcting for interstellar extinction of the luminosity because of gas and dust.

[36] Several problems complicate the use of Cepheids as standard candles and are actively debated, chief among them are: the nature and linearity of the period-luminosity relation in various passbands and the impact of metallicity on both the zero-point and slope of those relations, and the effects of photometric contamination (blending) and a changing (typically unknown) extinction law on Cepheid distances.

Resolving this discrepancy is one of the foremost problems in astronomy since some cosmological parameters of the Universe may be constrained significantly better by supplying a precise value of the Hubble constant.

[46][47] Cepheid variable stars were the key instrument in Edwin Hubble's 1923 conclusion that M31 (Andromeda) was an external galaxy, as opposed to a smaller nebula within the Milky Way.

[citation needed] As detected thus far, NGC 3370, a spiral galaxy in the constellation Leo, contains the farthest Cepheids yet found at a distance of 29 Mpc.

After novae fade, they are about as bright as the most luminous Cepheid variable stars, therefore both these techniques have about the same max distance: ~ 20 Mpc.

US astronomer William Alvin Baum first attempted to use globular clusters to measure distant elliptical galaxies.

Canadian astronomer René Racine assumed the use of the globular cluster luminosity function (GCLF) would lead to a better approximation.

The planetary nebula luminosity function (PNLF) was first proposed in the late 1970s by Holland Cole and David Jenner.

These methods, though with varying error percentages, have the ability to make distance estimates beyond 100 Mpc, though it is usually applied more locally.

The reason is that objects bright enough to be recognized and measured at such distances are so rare that few or none are present nearby, so there are too few examples close enough with reliable trigonometric parallax to calibrate the indicator.

For example, Cepheid variables, one of the best indicators for nearby spiral galaxies, cannot yet be satisfactorily calibrated by parallax alone, though the Gaia space mission can now weigh in on that specific problem.

Instead, distance indicators whose origins are in an older stellar population (like novae and RR Lyrae variables) must be used.

For some of these different standard candles, the homogeneity is based on theories about the formation and evolution of stars and galaxies, and is thus also subject to uncertainties in those aspects.

Finding the value of the Hubble constant was the result of decades of work by many astronomers, both in amassing the measurements of galaxy redshifts and in calibrating the steps of the distance ladder.

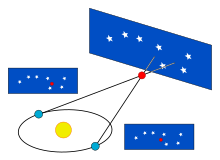

- Light green boxes: Technique applicable to star-forming galaxies .

- Light blue boxes: Technique applicable to population II galaxies.

- Light Purple boxes: Geometric distance technique.

- Light Red box: The planetary nebula luminosity function technique is applicable to all populations of the Virgo Supercluster .

- Solid black lines: Well calibrated ladder step.

- Dashed black lines: Uncertain calibration ladder step.