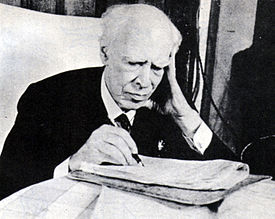

Konstantin Stanislavski

[4] Stanislavski (his stage name) performed and directed as an amateur until the age of 33, when he co-founded the world-famous Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) company with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, following a legendary 18-hour discussion.

[7] He collaborated with the director and designer Edward Gordon Craig and was formative in the development of several other major practitioners, including Vsevolod Meyerhold (whom Stanislavski considered his "sole heir in the theatre"), Yevgeny Vakhtangov, and Michael Chekhov.

[8] At the MAT's 30-year anniversary celebrations in 1928, a massive heart attack on-stage put an end to his acting career (though he waited until the curtain fell before seeking medical assistance).

[16] He produced his early work using an external, director-centred technique that strove for an organic unity of all its elements—in each production he planned the interpretation of every role, blocking, and the mise en scène in detail in advance.

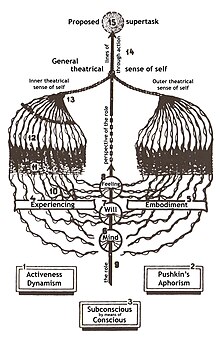

[22] Stanislavski organised his techniques into a coherent, systematic methodology, which built on three major strands of influence: (1) the director-centred, unified aesthetic and disciplined, ensemble approach of the Meiningen company; (2) the actor-centred realism of the Maly; and (3) the Naturalistic staging of Antoine and the independent theatre movement.

[42] After his debut performance at one in 1877, he started what would become a lifelong series of notebooks filled with critical observations on his acting, aphorisms, and problems—it was from this habit of self-analysis and critique that Stanislavski's system later emerged.

[47] Instead, he devoted particular attention to the performances of the Maly Theatre, the home of Russian psychological realism (as developed in the 19th century by Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol and Mikhail Shchepkin).

[68] Whereas the Ensemble's effects tended toward the grandiose, Stanislavski introduced lyrical elaborations through the mise-en-scène that dramatised more mundane and ordinary elements of life, in keeping with Belinsky's ideas about the "poetry of the real".

[71]Benedetti argues that Stanislavski's task at this stage was to unite the realistic tradition of the creative actor inherited from Shchepkin and Gogol with the director-centred, organically unified Naturalistic aesthetic of the Meiningen approach.

[76] Stanislavski later compared their discussions to the Treaty of Versailles, their scope was so wide-ranging; they agreed on the conventional practices they wished to abandon and, on the basis of the working method they found they had in common, defined the policy of their new theatre.

[81] In an atmosphere more like a university than a theatre, as Stanislavski described it, the company was introduced to his working method of extensive reading and research and detailed rehearsals in which the action was defined at the table before being explored physically.

[86] The production's success was due to the fidelity of its delicate representation of everyday life, its intimate, ensemble playing, and the resonance of its mood of despondent uncertainty with the psychological disposition of the Russian intelligentsia of the time.

[99] He also staged other important Naturalistic works, including Gerhart Hauptmann's Drayman Henschel, Lonely People, and Michael Kramer and Leo Tolstoy's The Power of Darkness.

[129]Stanislavski's preparations for Maeterlinck's The Blue Bird (which was to become his most famous production to-date) included improvisations and other exercises to stimulate the actors' imaginations; Nemirovich described one in which the cast imitated various animals.

[148] Inspired by a popular theatre performance in Naples that employed the techniques of the commedia dell'arte, Gorky suggested that they form a company, modeled on the medieval strolling players, in which a playwright and group of young actors would devise new plays together by means of improvisation.

[153] Despite these contrasting approaches, the two practitioners did share some artistic assumptions; the system had developed out of Stanislavski's experiments with Symbolist drama, which had shifted his attention from a Naturalistic external surface to the characters' subtextual, inner world.

[155] Their production attracted enthusiastic and unprecedented worldwide attention for the theatre, placing it "on the cultural map for Western Europe", and it has come to be regarded as a seminal event that revolutionised the staging of Shakespeare's plays.

[163] Other European classics directed by Stanislavski include: Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, Twelfth Night, and Othello, an unfinished production of Molière's Tartuffe, and Beaumarchais's The Marriage of Figaro.

[citation needed] Following the success of his production of A Month in the Country, Stanislavski made repeated requests to the board of the MAT for proper facilities to pursue his pedagogical work with young actors.

[166] Its founding members included Yevgeny Vakhtangov, Michael Chekhov, Richard Boleslawski, and Maria Ouspenskaya, all of whom would exert a considerable influence on the subsequent history of theatre.

[173] He hoped that the successful application of his system to opera, with its inescapable conventionality and artifice, would demonstrate the universality of his approach to performance and unite the work of Mikhail Shchepkin and Feodor Chaliapin.

[193] As a result of his conversations with Edward Gordon Craig, Copeau had come to believe that his work at the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier shared a common approach with Stanislavski's investigations at the MAT.

[201] During the years of the Civil War, Stanislavski concentrated on teaching his system, directing (both at the MAT and its studios), and bringing performances of the classics to new audiences (such as factory workers and the Red Army).

[223] On his return to Moscow in August 1924, Stanislavski began with the help of Gurevich to make substantial revisions to his autobiography, in preparation for a definitive Russian-language edition, which was published in September 1926.

[226] With a company fully versed in his system, Stanislavski's work on Mikhail Bulgakov's The Days of the Turbins focused on the tempo-rhythm of the production's dramatic structure and the through-lines of action for the individual characters and the play as a whole.

[228] Aware of the disapproval of Bulgakov felt by the Repertory Committee (Glavrepertkom) of the People's Commissariat for Education, Stanislavski threatened to close the theatre if the play was banned.

[240] Gurevich became increasingly concerned that splitting An Actor's Work into two books would not only encourage misunderstandings of the unity and mutual implication of the psychological and physical aspects of the system, but would also give its Soviet critics grounds on which to attack it: "to accuse you of dualism, spiritualism, idealism, etc.

[259] Consequently, the actor must also adopt a different point of view in order to plan the role in relation to its dramatic structure; this might involve adjusting the performance by holding back at certain moments and playing full out at others.

[268] The system stood accused of philosophical idealism, of a-historicism, of disguising social and political problems under ethical and moral terms, and of "biological psychologism" (or "the suggestion of fixed qualities in nature").

[268] In the wake of the first congress of the USSR Union of Writers (chaired by Maxim Gorky in August 1934), however, Socialist realism was established as the official party line in aesthetic matters.