Stanley Park

The park borders the neighbourhoods of West End and Coal Harbour to its southeast, and is connected to the North Shore via the Lions Gate Bridge.

Much of the park remains as densely forested as it was in the late 1800s, with about a half million trees, some of which stand as tall as 76 metres (249 ft) and are hundreds of years old.

[10][12] The site of Chaythoos is noted on a brass plaque placed on the lowlands east of Prospect Point commemorating the park's centennial.

Vancouver also wrote about meeting the people living there:Here we were met by about fifty [natives] in canoes, who conducted themselves with great decorum and civility, presenting us with several fish cooked and undressed of a sort resembling smelt.

[16] The peninsula was a popular place for gathering traditional food and materials in the 1800s, but it started to see even more activity after the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush in 1858, going through a succession of uses when non-Indigenous settlers moved into the area.

August Jack Khatsahlano, a celebrated dual chief of the Squamish and Musqueam who once lived at Chaythoos, remembered how he used to fish-rake in Coal Harbour and catch many herrings.

Second Beach was a source of "clay ... which, when rolled into loaves, as (my people) did it, and heated or roasted before a fire, turned into a white like chalk" that was used to make wool blankets.

[11]: 21 Indigenous inhabitants also cut down large cedar trees in the area for a variety of traditional purposes, such as making dugout canoes.

Despite the houses and cabins on the land, it was again considered a strategic point in case Americans attempted an invasion and launched an attack on New Westminster (then the colonial capital) via Burrard Inlet.

He cleared close to 40 hectares (100 acres) with the permission of colonial officials, but the site proved too impractical and he moved his operation east, eventually becoming Hastings Mill.

[13] In 1886, as its first order of business, Vancouver City Council voted to petition the British government to lease the military reserve for use as a park.

An observer at the event wrote: Lord Stanley threw his arms to the heavens, as though embracing within them the whole of 1000 acres of primeval forest, and dedicated it "to the use and enjoyment of peoples of all colours, creeds, and customs, for all time.

[20] Although most residents of the area were evicted by the early 20th century, the municipal government still owns a number of field homes used by the park's "live-in caretakers".

[30] The causeway was widened and extended through the centre of the park in the 1930s with the construction of the Lions Gate Bridge, which connects downtown Vancouver to the North Shore.

From there, a trail continues 600 metres (2,000 ft) to the west, connecting to an additional 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) of beaches and pathways that terminate at the mouth of the Fraser River.

[25]: 165 In 1936, when the Empire of Japan began large-scale military repression in northeast China, the perceived Japanese threat resulted in fortifications being erected in Stanley Park, among other areas.

[38] In Stanley Park, a watch tower was built on the cliff directly above Siwash Rock and remains intact as an observation deck that is accessed from the trails above.

The military also expanded its use of the park by closing the area around Ferguson Point and Third Beach, where it had established barracks for the battery detachment and was providing training.

The army built several other coastal defence forts for the Second World War, as shown in the illustration at right, most notably at Tower Beach in Point Grey.

The Stanley Park Zoo closed completely in December 1997 after the last remaining animal, a polar bear named Tuk, died at age 36.

The first was a combination of an October windstorm in 1934 and a subsequent snowstorm the following January that felled thousands of trees, primarily between Beaver Lake and Prospect Point.

[46][47] Another storm in October 1962, the remnants of Typhoon Freda, cleared a 2.4-hectare (6-acre) virgin tract behind the children's zoo, which opened an area for a new miniature railway that replaced a smaller version built in the 1940s.

The “Seven Sisters” are memorialized by a plaque and young replacement trees in the same location along Lovers Walk, a forest trail that connects Beaver Lake with Second Beach.

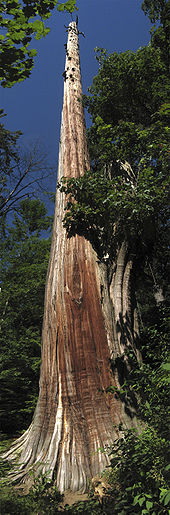

It diminished over time, ravaged by storms, a lightning strike, and topped by park staff to a height of 39.6 metres (130 ft) before being uprooted in October 2007.

[54][55] Damaged by the December 2006 windstorm and leaning forward at a dangerous angle, on March 31, 2008, the tree was selected by the Vancouver Park Board for removal due to potential safety hazards.

It was deemed significant because the relationship between its "natural environmental and its cultural elements developed over time" and because "it epitomizes the large urban park in Canada".

[70] The 2006 windstorm revealed traces of a long-forgotten rock garden, which had once been one of the park's star attractions and one of its largest man-made objects by area.

[71][72] Soon after its discovery, a section that encircles part of the Stanley Park Pavilion was restored (the garden had originally extended from Pipeline Road to Coal Harbour).

[74][75] Lost Lagoon, the captive 17-hectare (41-acre) freshwater lake near the Georgia Street entrance to the park, is a nesting ground to many bird species, such as Canada geese and ducks.

As an exception to the ban, the park board agreed in 2006 to build a new playground at Ceperley Meadows near Second Beach honouring the victims of the Air India Flight 182 bombing.