Steady-state economy

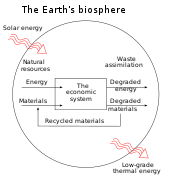

This vision is opposed to mainstream neoclassical economics, where the economy is represented by an isolated and circular model with goods and services exchanging endlessly between companies and households, without exhibiting any physical contact to the natural environment.

The incomes from gross production were distributed as rents, profits and wages among landowners, capitalists and labourers respectively, and these three classes were incessantly engaged in the struggle for increasing their own share.

[5]: 78f Smith was unable to provide any contemporary examples of a nation in the world that had in fact reached the full complement of riches and thus had settled in stationarity, because, as he conjectured, "... perhaps no country has ever yet arrived at this degree of opulence.

The Continental System brought into effect a large-scale embargo against British trade, whereby the nation's food supply came to rely heavily on domestic agriculture to the benefit of the landowning classes.

When the wars ended with Napoleon's final defeat in 1815, the landowning classes dominating the British parliament had managed to tighten the existing Corn Laws in order to retain their monopoly status on the home market during peacetime.

In the wake of the wartime period, the British economy seemed to be approaching the stationary state as population was growing, plots of land with lower fertility were put into agricultural use, and the rising rents of the rural landowning class were crowding out the profits of the urban capitalists.

"[23]: 593 According to Mill, the stationary state was at one and the same time inevitable, necessary and desirable: It was inevitable, because the accumulation of capital would bring about a falling rate of profit that would diminish investment opportunities and hamper further accumulation; it was also necessary, because mankind had to learn how to reduce its size and its level of consumption within the boundaries set by nature and by employment opportunities; finally, the stationary state was desirable, as it would ease the introduction of public income redistibution schemes, create more equality and put an end to man's ruthless struggle to get by — instead, the human spirit would be liberated to the benefit of more elevated social and cultural activities, 'the graces of life'.

Writing at the beginning of the Great Depression, Keynes rejected the prevailing "bad attack of economic pessimism" of his own time and foresaw that by 2030, the grandchildren of his generation would live in a state of abundance, where saturation would have been reached.

People would find themselves liberated from such economic activities as saving and capital accumulation, and be able to get rid of 'pseudo-moral principles' — avarice, exaction of interest, love of money — that had characterized capitalistic societies so far.

[30]: 3–6 In his magnum opus on The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Keynes looked only one generation ahead into the future and predicted that state intervention balancing aggregate demand would by then have caused capital accumulation to reach the point of saturation.

The marginal efficiency of capital as well as the rate of interest would both be brought down to zero, and — if population was not increasing rapidly — society would finally "... attain the conditions of a quasi-stationary community where change and progress would result only from changes in technique, taste, population and institutions ..."[31]: 138f Keynes believed this development would bring about the disappearance of the rentier class, something he welcomed: Keynes argued that rentiers incurred no sacrifice for their earnings, and their savings did not lead to productive investments unless aggregate demand in the economy was sufficiently high.

[17]: xiii Daly argues that nature has provided basically two sources of wealth at man's disposal, namely a stock of terrestrial mineral resources and a flow of solar energy.

[17]: 21f Daly points out that today's global ecological problems are rooted in man's historical record: Until the Industrial Revolution that took place in Britain in the second half of the 18th century, man lived within the limits imposed by what Daly terms a 'solar-income budget': The Palaeolithic tribes of hunter-gatherers and the later agricultural societies of the Neolithic and onwards subsisted primarily — though not exclusively — on earth's biosphere, powered by an ample supply of renewable energy, received from the Sun.

Daly cautions that more than two hundred years of worldwide industrialisation is now confronting mankind with a range of problems pertaining to the future existence and survival of our species: The entire evolution of the biosphere has occurred around a fixed point — the constant solar-energy budget.

[17]: 23 Following the work of Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, Daly argues that the laws of thermodynamics restrict all human technologies and apply to all economic systems: Entropy is the basic physical coordinate of scarcity.

[17]: 41 Once it is recognised that scarcity is imposed by nature in an absolute form by the laws of thermodynamics and the finitude of earth; and that some human wants are only relative and not worthy of satisfying; then we are all well on the way to the paradigm of a steady-state economy, Daly concludes.

Whereas the classical economists believed that the final stationary state would settle by itself as the rate of profit fell and capital accumulation came to an end (see above), Daly wants to create the steady-state politically by establishing three institutions of the state as a superstructure on top of the present market economy: The purpose of these three institutions is to stop and prevent further growth by combining what Daly calls "a nice reconciliation of efficiency and equity" and providing "the ecologically necessary macrocontrol of growth with the least sacrifice in terms of microlevel freedom and variability.

[66] The following issues have raised much concern worldwide: Air pollution emanating from motor vehicles and industrial plants is damaging public health and increasing mortality rates.

Even worse, the loss of Arctic permafrost may be triggering a massive release of methane and other greenhouse gases from thawing soils in the region, thereby overwhelming political action to counter climate change.

The era of relatively peaceful economic expansion that has prevailed globally since World War II may be interrupted by unexpected supply shocks or simply be succeeded by the peaking depletion paths of oil and other valuable minerals.

Tropical rainforests have been subject to deforestation at a rapid pace for decades — especially in west and central Africa and in Brazil — mostly due to subsistence farming, population pressure, and urbanization.

The experts write: "Until now, undernutrition and obesity have been seen as polar opposites of either too few or too many calories [...] In reality, they are both driven by the same unhealthy, inequitable food systems, underpinned by the same political economy that is single-focused on economic growth, and ignores the negative health and equity outcomes.

This ultra-egalitarian path will then make ecological room for poorer countries to catch up and combine into a final world steady-state, maintained at some internationally agreed upon intermediate and 'optimum' level of activity for some period of time — although not forever.

[130] British ecological economist Tim Jackson published Prosperity Without Growth, drawing extensively from an earlier report authored by him for the UK Sustainable Development Commission.

Some proponents may even reject modern civilization as such, either partly or completely, whereby the concept of a declining-state economy begins bordering on the ideology of anarcho-primitivism, on radical ecological doomsaying or on some variants of survivalism.

Romanian American economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen was the teacher and mentor of Herman Daly and is presently considered the main intellectual figure influencing the degrowth movement that formed in France and Italy in the early 2000s.

Fully aware of the massive growth dynamics of capitalism, Herman Daly on his part poses the rhetorical question whether his concept of a steady-state economy is essentially capitalistic or socialistic.

Herman Daly countered O'Neill's vision by arguing that a space colony would become subject to much harsher limits to growth — and hence, would have to be secured and managed with much more care and discipline — than a steady-state economy on large and resilient earth.

The building up of industrial infrastructure in space would be required for the purpose, as well as the establishment of a complete supply chain up to the level of self-sufficiency and then beyond, eventually developing into a permanent extraterrestrial source of wealth to provide an adequate return on investment for stakeholders.

[138][139][140] However, it is yet uncertain whether an off-planet economy of the type specified will develop in due time to match both the volume and the output mix needed to fully replace earth's dwindling mineral reserves.