Stedinger Crusade

When an attempt by the secular authorities to put down the revolt ended in defeat, the archbishop mobilized his church and the Papacy to have a crusade sanctioned against the rebels.

[1] Legally most of the Stedinger were subjects of the prince-archbishop of Bremen, the land being administered by his ministerials (serfs of knightly rank).

[2] Already in 1106 they had received privileges from Archbishop Frederick I conferring on them the right to freehold land and to found churches, as well as exempting them from some taxes.

Specifically, the Stedinger complained that the archbishop was demanding more in tax than he was owed and that both he and the count intended to convert their freeholds into leases.

Just before Christmas 1229,[a] he excommunicated the Stedingers for their continued refusal to pay taxes and tithes[2] (in the words of the Chronica regia Coloniensis, "for their excesses", pro suis excessibus).

[5] They were accused, among other things, of superstitious practices, murdering priests, burning churches and monasteries and desecrating the eucharist.

[4] Si ea que already permitted the investigators to request military assistance from the neighbouring nobility if the charges proved true.

[4] On 29 October 1232, he sent the letter Lucis eterne lumine authorising the preaching of a crusade against the Stedinger to the bishops of Minden, Lübeck and Ratzeburg.

[2] In his letter, Gregory accused the Stedinger of holding orgies and worshiping demons in Satanic rites—on top of their theological errors.

[2] On 19 January 1233, Gregory IX addressed the letter Clamante ad nos to bishops Wilbrand of Paderborn and Utrecht, Conrad II of Hildesheim, Luder of Verden, Ludolf of Münster and Conrad I of Osnabrück asking them to assist the bishops of Minden, Lübeck and Ratzeburg in preaching the crusade.

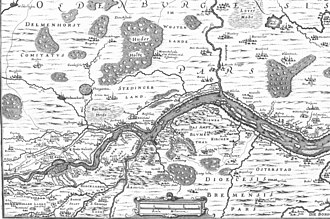

[1] The bishops of Minden, Lübeck and Ratzeburg reported to the pope the Stedinger's victories and the reluctance of many to join the crusade because they considered Stedingen naturally fortified by its numerous rivers and streams.

[6] In Littere vestre nobis, the plenary indulgence (full remission) was granted not only to those who died (as before) but to all who had taken the cross (i.e., a formal crusade vow) and fought.

[4] A larger and more impressive army was raised in early 1234,[2] after the Dominicans preached the crusade throughout Brabant, Flanders, Holland, the Rhineland and Westphalia.

[4] According to the Annales Stadenses, the response this time was enthusiastic, but Emo of Wittewierum records that there was widespread uncertainty over whether all those preaching the crusade had the correct authorization to do so.

Nearby, in a place called Stets, a local monk interrupted a Dominican's sermon and was imprisoned in Saint Juliana's Abbey in Rottum.

[j][1][8] A last-ditch effort to prevent bloodshed was made by the Teutonic Order, which intervened with the pope on behalf of the Stedinger.

On 18 March 1234, in the letter Grandis et gravis, Gregory ordered his legate in Germany, William of Modena, to mediate the dispute between the Stedinger and the archbishop.

Since the conflict was not resolved before the spring campaign, either word of the pope's decision did not reach the crusaders in time or the archbishop ignored it.

The sources vary in the number of dead they give: 2,000 (Chronica regia Coloniensis); 4,000 (Historia monasterii Rastedensis); 6,000 (Annales Stadenses); or 11,000 (Baldwin of Ninove).

According to the Historia monasterii Rastedensis, those who fled to Frisia and established a community there—the terra Rustringiae—were attacked by the counts of Oldenburg later in the century.

[1] After his victory at Altenesch, Archbishop Gerhard declared an annual day of remembrance to be kept in all the churches of the archdiocese of Bremen on the Saturday before the Feast of the Ascension.

He detailed the chants and hymns to be sung when and prescribed a solemn procession followed by an indulgence for twenty days afterwards to all who gave alms to the poor.

[1] The death of Hermann of Lippe in battle against the Stedinger was periodically remembered at the monastery of Lilienthal throughout the thirteenth century.

In endowing the church, Count Henry IV of Wildeshausen specifically mentioned his father, Burchard, and uncle, Henry III, "counts of Oldenburg killed under the banner of the holy cross against the Stedinger" (comitum de Aldenborch sub sancte crucis vexillo a Stedingis occisorum).

More recently, Rolf Köhn has argued that they were taken very seriously by contemporaries and reflected a real concern about the spread of heresy in Europe.