Stefan Zweig

In 1934, as a result of the Nazi Party's rise in Germany and the establishment of the Ständestaat regime in Austria, Zweig emigrated to England and then, in 1940, moved briefly to New York and then to Brazil, where he settled.

Nonetheless, as the years passed Zweig became increasingly disillusioned and despairing at the future of Europe, and he and his wife Lotte were found dead of a barbiturate overdose in their house in Petrópolis on 23 February 1942; they had died the previous day.

[9] Zweig served in the Archives of the Ministry of War and supported Austria's effort for war through his writings in the Neue Freie Presse and frequently celebrated in his Diaries the capture and massacre of opposing soldiers (for instance, writing about the innumerable citizens killed at gunpoint under the suspicion of espionage that "what filth has made ooze must be cauterized with scalding iron".)

In 1934, following Hitler's rise to power in Germany and the establishment of the Ständestaat, an authoritarian political regime now known as "Austrofascism", Zweig left Austria for England, living first in London, then from 1939 in Bath.

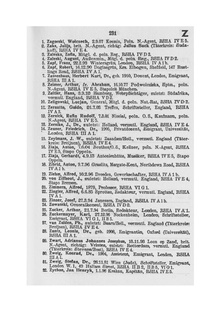

Because of the swift advance of Hitler's troops westwards, and the threat of arrest or worse – as part of the preparations for Operation Seelöwe a list of persons to be detained immediately after conquest of the British Isles, the so-called Black Book, had been assembled and Zweig was on page 231, with his London address fully mentioned – Zweig and his second wife crossed the Atlantic to the United States, settling in 1940 in New York City; they lived for two months as guests of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, before renting a house in Ossining, New York.

[18] Zweig, feeling increasingly depressed about the situation in Europe and the future for humanity, wrote in a letter to author Jules Romains, "My inner crisis consists in that I am not able to identify myself with the me of passport, the self of exile".

[29] Zweig is best known for his novellas (notably The Royal Game, Amok, and Letter from an Unknown Woman – which was filmed in 1948 by Max Ophüls), novels (Beware of Pity, Confusion of Feelings, and the posthumously published The Post Office Girl) and biographies (notably of Erasmus of Rotterdam, Ferdinand Magellan, and Mary, Queen of Scots, and also the posthumously published one on Balzac).

At one time his works were published without his consent in English under the pseudonym "Stephen Branch" (a translation of his real name) when anti-German sentiment was running high.

It has been widely discussed as a record of "what it meant to be alive between 1881 and 1942" in central Europe; the book has attracted both critical praise[25] and hostile dismissal.

He went on explaining that Freud had considerable influence on writers such as Marcel Proust, D.H. Lawrence and James Joyce, giving them a lesson in "courage" and helping them to overcome their inhibitions.

[33] Zweig enjoyed a close association with Richard Strauss and provided the libretto for Die schweigsame Frau (The Silent Woman).

Strauss famously defied the Nazi regime by refusing to sanction the removal of Zweig's name from the programme[34] for the work's première on 24 June 1935 in Dresden.

He corresponded at length with Hungarian musicologist Gisela Selden-Goth, often discussing their shared interest in collecting original music scores.

The 1933 Austrian-German drama film The Burning Secret directed by Robert Siodmak was based on Zweig's short story Brennendes Geheimnis.

The 1988 remake of the same film Burning Secret was directed by Andrew Birkin and starred Klaus Maria Brandauer and Faye Dunaway.

[46] The 2013 French film A Promise (Une promesse) is based on Zweig's novella Journey into the Past (Reise in die Vergangenheit).

In the film's opening sequence, a teenage girl visits a shrine for The Author, which includes a bust of him wearing Zweig-like spectacles and celebrated as his country's "National Treasure".

[49] TV film La Ruelle au clair de lune (1988) by Édouard Molinaro is an adaptation of Zweig's short-story Moonbeam Alley.