Stegoceras

Stegoceras is a genus of pachycephalosaurid (dome-headed) dinosaur that lived in what is now North America during the Late Cretaceous period, about 77.5 to 74 million years ago (mya).

[1] In 1903, Hungarian palaeontologist Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás suggested that the fragmentary domes of Stegoceras were in fact frontal and nasal bones, and that the animal would therefore have had a single, unpaired horn.

[5][6] Hatcher doubted whether the Stegoceras specimens belonged to the same species and whether they were dinosaurs at all, and suggested the domes consisted of the frontal, occipital, and parietal bones of the skull.

It was discovered in the Belly River Group by the American palaeontologist George F. Sternberg in 1926, and catalogued as specimen UALVP 2 in the University of Alberta Laboratory for Vertebrate Palaeontology.

[14] In 1974, the Polish palaeontologists Teresa Maryańska and Halszka Osmólska concluded that the "gastralia" of Stegoceras were ossified tendons, after identifying such structures in the tail of the pachycephalosaur Homalocephale.

[15] In 1983, Galton and Hans-Dieter Sues moved S. browni to its own genus, Ornatotholus (ornatus is Latin for "adorned" and tholus for "dome"), and considered it the first known American member of a group of "flat-headed" pachycephalosaurs, previously known from Asia.

[21] In 2023, Aaron D. Dyer and colleagues analysed sutures and individual elements in the skulls of the pachycephalosaurs Gravitholus and Hanssuesia, and found no significant distinction between them and Stegoceras validum.

S. novomexicanum (difficult to identify), but found it likely they all belonged to the same taxon (with the assigned specimens being adults), due to the restricted stratigraphic interval and geographic range.

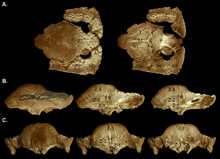

[3] The skull of Stegoceras can be distinguished from those of other pachycephalosaurs by features such as its pronounced parietosquamosal shelf (though this became smaller with age), the "incipient" doming of its frontopariental (though the doming increased with age), its inflated nasal bones, its ornamentation of tubercles on the sides and back of the squamosal bones, rows of up to six tubercles on the upper side of each squamosal, and up to two nodes on the backwards projection of the parietal.

The articulation between the zygagophyses (articular processes) of successive dorsal (back) vertebrae appears to have prevented sideways movement of the vertebral column, which made it very rigid, and it was further strengthened by ossified tendons.

In 1978, the Chinese palaeontologist Dong Zhiming split Pachycephalosauria into two families; the dome-headed Pachycephalosauridae (including Stegoceras) and the flat-headed Homalocephalidae (originally spelled Homalocephaleridae).

In 1986, American palaeontologist Paul Sereno supported the relationship between pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians, and united them in the group Marginocephalia, based on similar cranial features, such as the "shelf"-structure above the occiput.

Pachycephalosaurs and Thescelosaurids occur in the same North American formations, and it appears that their coexistence was made possible by them occupying different ecomorphospaces (though Stegoceras and Thescelosaurus themselves were not contemporaries).

[42] In 1989, Emily B. Griffin found that Stegoceras and other pachycephalosaurs had a good sense of smell (olfaction), based on the study of cranial endocasts that showed large olfactory bulbs in the brain.

Brown and Schlaikjer suggested that there was sexual dimorphism in the degree of doming, and hypothesized that flat-headed specimens such as AMNH 5450 (Ornatotholus) represented the female morph of Stegoceras.

They suggested that juveniles were characterized by a flat, thickened frontoparietal roof, with larger supratemporal fenestrae, and studded with closely spaced tubercles and nodes.

He believed it was unlikely to have been used mainly as defence against predators, because the dome itself lacked spikes, and those of the parietosquamosal shelf were in an "ineffective" position, but found it compatible with intra-specific competition.

Modern bighorn sheep and bison overcome this problem by having strong ligaments from the neck to the tall neural spines over the shoulders (which absorb the force of impact), but such features are not known in pachycephalosaurs.

Carpenter suggested that the pachycephalosaurs would have first engaged in threat display by bobbing and presenting their heads to show the size of their domes (intimidation), and thereafter delivered blows to each other, until one opponent signalled submission.

[51] In 2011, Snively and Jessica M. Theodor conducted a finite element analysis by simulating head-impacts with CT scanned skulls of S. validum (UALVP 2), Prenocephale prenes and several extant head-butting artiodactyls.

Though Stegoceras lacked the pneumatic sinuses that are found below the point of impact in the skulls of head-striking artiodactyls, it instead had vascular struts which could have similarly acted as braces, as well as conduits to feed the development of a keratin covering.

Brown and Russell found that the tail could thereby help in resisting compressive, tensile, and torsional loading when the animal delivered or received blows with the dome.

These areas had large muscles, and combined with the wide pelvis and stout hind limbs (and possibly enlarged ligaments), this resulted in a strong, stable pelvic structure that would have helped during head-butting between individuals.

Since the skull domes of pachycephalosaurs grew with positive allometry, and may have been used in combat, these researchers suggested it may have been the case for the hindlimb muscles as well, if they were used to propel the body forwards during head-butting.

[48] In 2011, American palaeontologists Kevin Padian and John R. Horner proposed that "bizarre structures" in dinosaurs in general (including domes, frills, horns, and crests) were primarily used for species recognition, and dismissed other explanations as unsupported by evidence.

Among other studies, these authors cited Goodwin et al.'s 2004 paper on pachycephalosaur domes as support of this idea, and they pointed out that such structures did not appear to be sexually dimorphic.

[27] It has traditionally been suggested that pachycehalosaurs inhabited mountain environments; wear of their skulls was supposedly a result of them having been rolled by water from upland areas, and comparisons with bighorn sheep reinforced the theory.

In 2014, Jordan C. Mallon and Evans disputed this idea, as the wear and original locations of the skulls is not consistent with having been transported in such a way, and they instead proposed that North American pachycephalosaurs inhabited alluvial (associated with water) and coastal plain environments.

[58] The Dinosaur Park Formation is interpreted as a low-relief setting of rivers and floodplains that became more swampy and influenced by marine conditions over time as the Western Interior Seaway transgressed westward.

As well as Stegoceras, the formation has also yielded fossils of the ceratopsians Centrosaurus, Styracosaurus and Chasmosaurus, the hadrosaurids Prosaurolophus, Lambeosaurus, Gryposaurus, Corythosaurus, and Parasaurolophus, and the ankylosaurs Edmontonia and Euoplocephalus.