Stereotype threat

[11] Repeated experiences of stereotype threat can lead to a vicious circle of diminished confidence, poor performance, and loss of interest in the relevant area of achievement.

[17] Some researchers have suggested that stereotype threat should not be interpreted as a factor in real-life performance gaps, and have raised the possibility of publication bias.

[21] However, meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown significant evidence for the effects of stereotype threat, though the phenomenon defies over-simplistic characterization.

[22][24] Stereotype threat is considered by some researchers to be a contributing factor to long-standing racial and gender achievement gaps, such as under-performance of black students relative to white ones in various academic subjects, and under-representation of women at higher echelons in the field of mathematics.

[35] The goal of a study conducted by Desert, Preaux, and Jund in 2009 was to see if children from lower socioeconomic groups are affected by stereotype threat.

Scheepers and Ellemers tested the following hypothesis: when assessing a performance situation on the basis of current beliefs the low status group members would show a physiological threat response, and high-status members would also show a physiological threat response when examining a possible alteration of the status quo (Scheepers & Ellemers, 2005).

The single largest experimental test of stereotype threat (N = 2064), conducted on Dutch high school students, found no effect.

[45] The authors state, however, that these results are limited to a narrow age-range, experimental procedure and cultural context, and call for further registered reports and replication studies on the topic.

A number of studies looking at physiological and neurological responses support Schmader and colleagues' integrated model of the processes that produce stereotype threat.

Supporting an explanation in terms of stress arousal, one study found that African Americans under stereotype threat exhibit larger increases in arterial blood pressure.

With regard to performance monitoring and vigilance, studies of brain activity have supported the idea that stereotype threat increases both of these processes.

Forbes and colleagues recorded electroencephalogram (EEG) signals that measure electrical activity along the scalp, and found that individuals experiencing stereotype threat were more vigilant for performance-related stimuli.

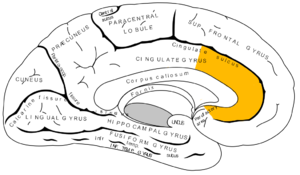

The researchers found that women experiencing stereotype threat while taking a math test showed heightened activation in the ventral stream of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a neural region thought to be associated with social and emotional processing.

[58] The heightened activation in these brain areas also was associated with better memory accuracy, inconsistent with the notion that stereotype threat always leads to impaired performance.

Steele and Aronson concluded that changing the instructions on the test could reduce African-American students' concern about confirming a negative stereotype about their group.

Supporting this conclusion, they found that African-American students who regarded the test as a measure of intelligence had more thoughts related to negative stereotypes of their group.

[79] Cross-sectional studies involving diverse minority groups, including those relating to internalized racism, have found that individuals who experience more perceived discrimination are more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms.

[82][83] Other negative mental health outcomes associated with perceived discrimination include a reduced general well-being, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and rebellious behavior.

[79] A meta-analysis conducted by Pascoe and Smart Richman has shown that the strong link between perceived discrimination and negative mental health persists even after controlling for factors such as education, socioeconomic status, and employment.

[84] Additional research seeks ways to boost the test scores and academic achievement of students in negatively stereotyped groups.

One such study found that a self-affirmation exercise (in the form of a brief in-class writing assignment about a value that is important to them) significantly improved the grades of African-American middle-school students, and reduced the racial achievement gap by 40%.

[92] Similarly, it has been shown that encouraging women to think about their multiple roles and identities by creating self-concept map can eliminate the gender gap on a relatively difficult standardized test.

[98] One early study suggested that simply informing college women about stereotype threat and its effects on performance was sufficient to eliminate the predicted gender gap on a difficult math test.

It was found that "women who properly understood the meaning of the information provided, and thus became knowledgeable about stereotype threat, performed significantly worse at a calculus task".

[100] In such cases, further research suggests that the manner in which the information is presented –– that is, whether subjects are made to perceive themselves as targets of negative stereotyping –– may be decisive.

[21] Sackett et al. argued that, in Steele and Aronson's (1995) experiments where stereotype threat was mitigated, an achievement gap of approximately one standard deviation remained between the groups, which is very close in size to that routinely reported between African American and European Americans' average scores on large-scale standardized tests such as the SAT.

"[24] Despite these limitations, they found that efforts to mitigate stereotype threat significantly reduced group differences on high-stakes tests.

[105] However, a subsequent study by Johannes Keller specifically controlled for Jensen's hypothesis and still found significant stereotype threat effects.

[106] Gijsbert Stoet and David C. Geary reviewed the evidence for the stereotype threat explanation of the achievement gap in mathematics between men and women.

[18] Positing that large, well-controlled studies have tended to find smaller or non-significant effects, the authors argued that evidence for stereotype threat in children may reflect publication bias.