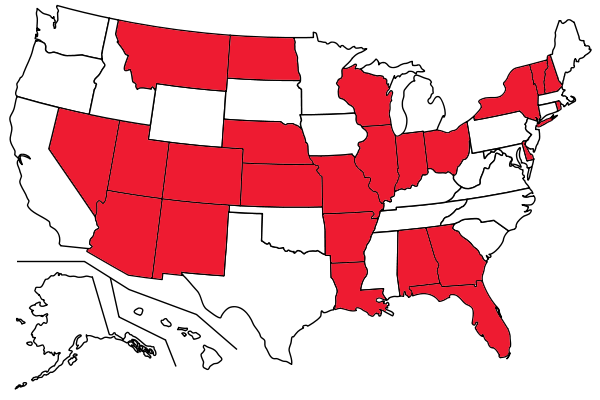

Stop and identify statutes

"Stop and identify" statutes are laws in several US states; Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Utah, and Wisconsin.

[2] The Fourth Amendment prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures and requires warrants to be supported by probable cause.

For instance, in Kolender v. Lawson (1983), the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a California law requiring "credible and reliable" identification as overly vague.

Additional states (including Arizona, Texas, South Dakota and Oregon) have such laws just for motorists,[6][7][8] which penalize the failure to present a driver license during a traffic stop.

[18] As of February 2011[update], the Supreme Court has not addressed the validity of requirements that a detainee provide information other than their name.

Some states, such as Arizona, however, have specifically codified that a detained person is not required to provide any information aside from a full name.

On June 23, 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States voted six to three in the decision Vega v. Tekoh that police may not be sued for failing to administer a Miranda warning.

As a practical matter, an arrested person who refused to give their name would have little chance of obtaining a prompt release.

Some states listed have "stop and ID" laws which may or may not require someone to identify themself during an investigative detention.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court held in Henes v. Morrissey that "A crime is made up of two parts: proscribed conduct and a prescribed penalty.

When stopped by police while driving, the driver is legally required to present proof of their identity by Nevada law.

As of February 2011[update], the validity of a law requiring that a person detained provide anything more than stating their name has not come before the U.S. Supreme Court.

indicate that there is no requirement per se to provide physical identification, except when under arrest or while operating a motor vehicle on public roads.

[36] A similar conclusion regarding the interaction between Utah "stop and identify" and "obstructing" laws was reached in Oliver v. Woods (10th Cir.

[40] Some courts have recognized a distinction authorizing police to demand identifying information and specifically imposing an obligation of a suspect to respond.

04SC362 (2005) that refusing to provide identification was an element in the "totality of the circumstances" that could constitute obstructing an officer, even when actual physical interference was not employed.

For example, as the U.S. Supreme Court noted in Hiibel, California "stop and identify" statute was voided in Kolender v. Lawson.

But in People v. Long,[50] decided four years after Kolender, a California appellate court found no constitutional impropriety in a police officer's demand for written identification from a detainee whom they reasonably suspect of having committed a crime.

The issue before the Long court was a request for suppression of evidence uncovered in a search of the defendant's wallet, so the issue of refusal to present identification was not directly addressed; however, the author of the Long opinion had apparently concluded in a 1980 case that failure to identify oneself did not provide a basis for arrest.

[51] Nonetheless, some cite Long in maintaining that refusal to present written identification constitutes obstructing an officer.

[57] Conversely, West Virginia's courts decided that their resisting arrest statute did not include individuals who refused to identify themselves.

[58] Some legal organizations, such as the National Lawyers Guild and the ACLU of Northern California, recommend to either remain silent or to identify oneself whether or not a jurisdiction has a "stop and identify" law: In a more recent pamphlet, the ACLU of Northern California elaborated on this further, recommending that a person detained by police should: Many countries allow police to demand identification and arrest people who do not carry any (or refuse to produce such).