The Straits Times

Fellow Armenian and friend, Catchick Moses, then bought the printing equipment from Apcar and launched The Straits Times with Robert Carr Woods, Sr., an English journalist from Bombay as editor.

[15][16] The Straits Times became a major reporter of political and economic events of note in British Malaya, including shipping news, civil and political unrest in Siam and Burma, official reports, and including high society news items such as tea parties held at Government House and visits from dignitaries such as the Sultan of Johor.

Nothing fills us with greater contempt than the type of journalism, unfortunately somewhat on the increase in Great Britain, which pries into private affairs, gloats over domestic scandals, and tickles the palates of the people with snappy tidbits of personality.

The rival newspapers spurred readership among the growing English-reading community, with The Singapore Free Press published in the morning and The Straits Times released in the afternoon.

The Straits Times focused predominantly on British and British-related events while ignoring the politics and socio-economic issues of concern to other groups, including the Malay, Chinese, and Indian populations in and around Singapore.

Coverage of events related to non-British was typically restricted to court cases or sensationalized crimes, such as the Tok Janggut's rebellion in Kelantan in 1915.

Its single largest shareholder was the procurer of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, the Reverend N.J. Couvreur, who also served as the chairman of the company's board of the directors from 1910 to 1920.

In the 1920s and 1930s, The Straits Times began to face competition from other papers, specifically the Malaya Tribune, which promised "frank discussion of Malayan affairs" and "weekly articles by special and well-informed writers, Chinese, Indians, and Muslims".

In response to the competition, Seabridge improved the company by building a new office, replacing and updating old printing equipment, hiring local journalists, and beginning delivery upcountry.

[citation needed] Part of Seabridge's attempts to expand circulation was to include "women's columns", particularly by incorporating the voices of the wives of wealthy British planters.

[20] By 1933, the renewed Free Press was unable to maintain the competition with The Straits Times and the paper was bought by Seabridge, though it remained more closely affiliated with merchants and lawyers.

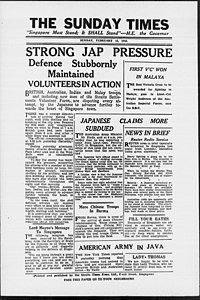

Similar evacuations of only Europeans were ordered throughout the month of December, seriously undermining the morale of the much larger Asian population of Singapore and the surrounding British areas.

The first issue of The Shonan Times published a declaration by Tomoyuki Yamashita, announcing that the aim of the Japanese was to establish the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in order to achieve a "Great Spirit of Cosmocrasy" and "sweep away the arrogant and unrighteous British elements".

[25][26] The children's newspaper, outlined in the third goal, was published as Sakura and included as a free supplement in the 10 June 1942 edition of the Syonan Shimbun, though it was later sold separately for one sen.

[33] From Batavia, Seabridge filed a secret report for the War Cabinet in London in April 1942 on the failure of both military and civilian governments to hold and maintain Singapore's defences.Singapore itself was in a state of almost complete chaos from the end of December.

[24]In June 1942, the Military Propaganda Squad (軍宣伝班) launched a campaign, Nippon-Go Popularising Week, to promote the Japanese language among Singaporeans, using the Syonan Shimbun.

[34] The children's newspaper, outlined in the third goal, was published as Sakura and included as a free supplement in the 10 June 1942 edition of the Syonan Shimbun, though it was later sold separately for one sen. On 11 March 1950, The Straits Times became a public limited company.

[36][37] Editors were warned by British colonial officials that any reportage that may threaten the merger between Singapore and the Malayan Federation may result in subversion charges, and that they may be detained without trial under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance Act.

[40] Earlier during the Emergency, The Straits Times had erroneously reported that 26 suspected communist guerrillas had been shot dead by the British military while attempting to escape after ammunition had been discovered in their homes.

[41] However, it was later discovered that 24 people had been shot dead, and that all of them were innocent civilians who had been executed as part of the Batang Kali massacre by the Scots Guards regiment; an event described by historians as the British Mỹ Lai.

[19] Prior to 1965, during the early days of Singaporean self-governance, the paper had an uneasy relationship with some politicians, including the leaders of the People's Action Party (PAP).

[47][48] This was partially due to Hoffman criticising the PAP during the 1959 general election and supporting the eventually defeated chief minister Lim Yew Hock.

[13] Editors were warned that any reportage that may threaten the merger between Singapore and the Malayan Federation may result in subversion charges, and that they may be detained without trial under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance Act.

[16] Subsequently, the Singaporean government restructured the entire newspaper industry, in which all papers published in English, Chinese, and Malay were brought under Singapore Press Holdings (SPH), established on 30 November 1984.

[55] Chua Chin Hon, then ST's bureau chief for the United States, was quoted as saying that SPH's "editors have all been groomed as pro-government supporters and are careful to ensure that reporting of local events adheres closely to the official line" in a 2009 US diplomatic cable leaked by WikiLeaks.

SPH CEO Alan Chan was a former top civil servant and Principal Private Secretary to then Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew.

The Home section consist of local news and topics on Education for Monday, Mind and Body for Tuesday, Digital for Wednesday, Community for Thursday and Science for Friday.

[8][9] Launched on 1 January 1994, The Straits Times' website was free of charge and granted access to all the sections and articles found in the print edition.

Currently, only people who subscribe to the online edition can read all the articles on the Internet, including the frequently updated "Latest News" section.

In July 2007, the National Library Board signed an agreement with the Singapore Press Holdings to digitise the archives of The Straits Times going back to its founding in 1845.