Strasbourg massacre

Its development found fertile territory in the religious and social resentments against Jews that had grown deeper over the centuries (with allegations such as host desecration, blood libel, and deicide).

The chroniclers report that Jews were criticised for their business practices: they were said to be so arrogant that they were unwilling to grant anyone else precedence, and those who dealt with them could hardly come to an agreement with them.

This supposed ruthlessness of the Jews did not, however, derive from any particular hard-heartedness, but was rather due to the huge levies and taxes that they were made to pay, mostly in exchange for protection.

Unlike the majority of the population, the council and the master tradesmen remained committed to the policy of protecting the Jews and attempted to calm the people and prevent a pogrom.

The Catholic clergy had been advised by two papal bulls of Pope Clement VI the previous year (July and September 1348) to preach against anyone accusing the Jews of poisoning wells as "seduced by that liar, the Devil."

Furthermore, the Jewish quarter was sealed off and guarded by armed persons, in order to protect the Jews from the population and possible over-reactions.

The master tradesmen wanted to maintain the legal process with respect to the Jews; in their situation in which they themselves increasingly came under attack, this was a matter of self-preservation and holding on to power.

How seriously this threat of revolt was taken is shown by a letter from the city council of Cologne on 12 January 1349 to the leaders of Strasbourg, which warned that such riots by the common people had led to much evil and devastation in other towns.

As the de facto master over the Jews, the city had a duty to protect them, especially since they paid significant amounts of money in exchange for this.

He, therefore could not and would not agree to an extermination of the Jews, a stance in which he was undoubtedly strengthened by the fear of the adverse effects on the economic development of the city.

The artisans, after an exhaustive debate which involved not only the guilds' representatives but also the most eminent of the knights and citizens, decided to make a new attempt.

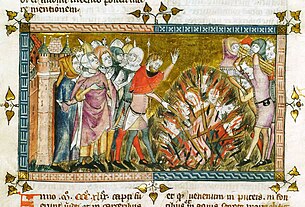

The guilds had thereby attained their goal: the last obstacle to their demand of destroying the Jews was pushed aside, and they now had increased possibilities of participating in town politics.

In the chronicles, this cooperation comes across again and again: the noble families brought their weapons at the same time as the craftsmen when the latter assembled before the cathedral, they were involved with the debates during the rebellion, and it was noblemen who put the demands to the masters, in the name of the artisans.