Strawman theory

[1] Pseudolaw advocates claim that it is possible, through the use of certain "redemption" procedures and documents, to separate oneself from the "strawman", therefore becoming free of the rule of law.

[4][5] Canadian legal scholar Donald J. Netolitzky has called the strawman theory "the most innovative component of the Pseudolaw Memeplex".

[9][10] The theory appeared circa 1999–2000, when it was conceived by North Dakota farmer turned pseudolegal activist Roger Elvick.

The strawman theory overlapped with those of the redemption movement: it eventually became a core concept of sovereign citizen ideology, as it connected their pseudolegal beliefs through an overarching explanation.

[2] Around the same period, this set of beliefs was introduced into Canada by Eldon Warman, a student of Elvick's theories who adapted them for a Canadian context.

[1] One argument used by proponents of the strawman theory is based on a misinterpretation of the term capitis deminutio, used in ancient Roman law for the extinguishment of a person's former legal capacity.

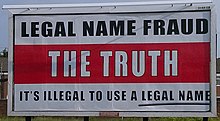

Adherents to the theory spell the term "Capitis Diminutio", and claim that capitis diminutio maxima (meaning, in Roman law, the loss of liberty, citizenship, and family) was represented by an individual's name being written in capital letters, hence the idea of individuals having a separate legal personality.

[19] His concepts relied on a misinterpretation of the definition of a "person" in section 248(1) of the Canadian Income Tax Act, which he combined with the strawman theory.

Proponents cite a misinterpretation of a passage in chapter 39 of King John's Magna Carta stating in part that, "no freeman will be seized, dispossessed of his property, or harmed except by the law of the land”.

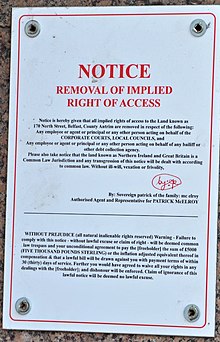

{[23] Adherents to the theory believe that separating from their strawman or refusing to be identified as such enables escape from their legal liabilities and responsibilities.

[2] The belief in the strawman articulates with the redemption movement's fraudulent debt and tax payment schemes, which imply that money from the secret account (known in some variations of the theory as a "Cestui Que Vie Trust"[25]) can be used to pay one's taxes, debts and other liabilities by simply writing phrases like "Accepted for Value" or "Taken for Value" on the bills or collection letters, or that the strawman's funds are accessible through the use of certain forms and securities.

[3][26] One purported "redemption" method for appropriating the money from the alleged secret account is to file a UCC-1 financing statement against one's strawman after having taken the steps to "separate" from it.

Lindsay's argument was that he had opted out of "personhood" in 1996, which made him "a full liability free will flesh and blood living man".

The Supreme Court of British Columbia rejected his claims, commenting that "The ordinary sense of the word 'person' in the (Income Tax Act) is without ambiguity.

[7] Judge Norman K. Moon found such tactics an unconvincing argument in 2013 when an individual named Brandon Gravatt tried to overturn a drug conviction and get out of prison.

"[33] In 2021, the District Court of Queensland dismissed an application that relied on the strawman theory, commenting that this argument "may properly be described as nonsense or gobbledygook".

These categories included, before 1833, slaves, who were regarded as chattel property, could be bought and sold, and who had no rights under the law.