Streetcars in New Orleans

Preservationists were unable to save the streetcars on Canal Street, but were able to convince the city government to protect the St. Charles Avenue Line by granting it historic landmark status.

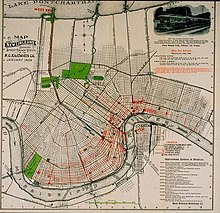

[3]: 6–7 As the area upriver (uptown) from the city began to be built up—much of the new development along the Nayades (St. Charles Avenue) corridor—additional lines were created by the New Orleans and Carrollton.

Like the Jackson line, these were horse- or mule-drawn cars, operating from Nayades Avenue to the river along their namesake streets.

[3]: 88–89 Up until about 1860, omnibus lines provided the only public transit outside the area serviced by the New Orleans and Carrollton RR.

The first line, Rampart and Esplanade (later called simply Esplanade), opened June 1, 1861, followed in quick succession by the Magazine, Camp and Prytania (later called Prytania), Canal, Rampart and Dauphine (later Dauphine), and finally Bayou Bridge and City Park.

[3]: 14–16 Lamm engines were actually adopted and used for a time on the New Orleans and Carrollton line, which had previously used steam locomotives.

The area between the town of Carrollton and the City of New Orleans was sparsely populated with large swaths of agricultural land when the line was laid out in the 1830s; by the latter 19th century it was almost completely urbanized.

[3]: 45–46 Labor problems began to occupy the attention of street railway officials as consolidation progressed.

They also demanded an increase in pay and recognition of their union, Division 194 of the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America.

After about two weeks of strife, a settlement was reached, and in early 1903, the company signed a contract and recognized the union.

At first this was objected to by both white and black riders as an inconvenience, and by the streetcar companies on grounds of both added expense and the difficulties of determining the racial background of some New Orleanians.

Other efficiencies were instituted, such as reducing the number of streetcar lines operating over long stretches of Canal Street.

Beginning after World War II, as in much of the United States, almost all streetcar lines were replaced with buses, either internal combustion (gasoline/diesel) or electric (trolley bus).

These signs could be moved forward or back in the vehicle as passenger loads changed during the operating day.

The area through which the St. Charles Avenue Line traveled fared comparatively well in Hurricane Katrina's devastating impact on New Orleans at the end of August 2005, with moderate flooding only of the two ends of the line at Claiborne Avenue and at Canal Street.

However, wind damage and falling trees took out many sections of trolley wire along St. Charles Avenue, and vehicles parked on the neutral ground (traffic medians) over the inactive tracks degraded parts of the right-of-way.

Leaving the line shut down and the electrical system unpowered allowed the upgrades to be performed more safely and easily.

The vintage green streetcars rode out the storm in the sealed barn in a portion of Old Carrollton that did not flood, and were undamaged.

Brookville Equipment Corporation (BEC) of Pennsylvania was awarded the contract to provide the components to rebuild 31 New Orleans' streetcars to help the city bring its transportation infrastructure closer to full capacity.

The streetcars were submerged in over five feet of water while parked in their car barn, and all electrical components affected by the flooding had to be replaced.

[16] BEC's engineering and drafting departments immediately began work on this three-year project to return these New Orleans icons to service.

[17] Painting, body work, and final assembly of the restored streetcars was carried out by RTA craftsmen at Carrollton Station Shops.

As of March 2009, sufficient red cars had been repaired to take over all service on the Canal Street and Riverfront lines.

[24] The St. Charles Avenue Line has traditionally used streetcars of the type that were common all over the United States in the early parts of the 20th century.

By 2010 enough restored streetcars were back in service to again confine the historic Perley Thomas cars to the St. Charles line.

957: When the Canal line was discontinued in 1964, this car was sold to the Trinity Valley Railroad Club in Weatherford, Texas, west of Fort Worth.

Then it was sold to the Spaghetti Warehouse Company, then to the McKinney Avenue Transit Authority in Dallas, Texas, and finally it was purchased by New Orleans RTA in 1986.

It was stored until 1997, when it was rebuilt with a wheelchair lift and modern controls, becoming the first of the new 457-463 series cars for the re-equipment of the Riverfront line.

913: This car was sold to the Orange Empire Railway Museum in Riverside County, California in 1964 when the Canal line was discontinued.

For a time, it was stored at Thomas Built Buses, the current name of its builder, Perley Thomas Car Co. 966: Owned by Seashore Trolley Museum, Kennebunkport, Maine, and operated at Lowell National Historical Park, Massachusetts.