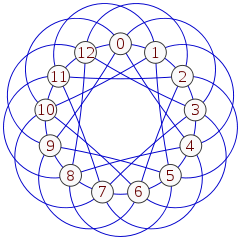

Strongly regular graph

Such a strongly regular graph is denoted by srg(v, k, λ, μ).

Its complement graph is also strongly regular: it is an srg(v, v − k − 1, v − 2 − 2k + μ, v − 2k + λ).

A strongly regular graph is denoted as an srg(v, k, λ, μ) in the literature.

By convention, graphs which satisfy the definition trivially are excluded from detailed studies and lists of strongly regular graphs.

These include the disjoint union of one or more equal-sized complete graphs,[1][2] and their complements, the complete multipartite graphs with equal-sized independent sets.

Andries Brouwer and Hendrik van Maldeghem (see #References) use an alternate but fully equivalent definition of a strongly regular graph based on spectral graph theory: a strongly regular graph is a finite regular graph that has exactly three eigenvalues, only one of which is equal to the degree k, of multiplicity 1.

This automatically rules out fully connected graphs (which have only two distinct eigenvalues, not three) and disconnected graphs (for which the multiplicity of the degree k is equal to the number of different connected components, which would therefore exceed one).

Strongly regular graphs were introduced by R.C.

[3] They built upon earlier work in the 1950s in the then-new field of spectral graph theory.

All the above graphs are primitive, as otherwise μ = 0 or λ = k. Conway's 99-graph problem asks for the construction of an srg(99, 14, 1, 2).

It is unknown whether a graph with these parameters exists, and John Horton Conway offered a $1000 prize for the solution to this problem.

[5] The strongly regular graphs with λ = 0 are triangle free.

Apart from the complete graphs on fewer than 3 vertices and all complete bipartite graphs, the seven listed earlier (pentagon, Petersen, Clebsch, Hoffman-Singleton, Gewirtz, Mesner-M22, and Higman-Sims) are the only known ones.

These are called the Moore graphs and are explored below in more detail.

Despite ongoing research on the properties that a strongly regular graph with

The four parameters in an srg(v, k, λ, μ) are not independent: In order for an srg(v, k, λ, μ) to exist, the parameters must obey the following relation: The above relation is derived through a counting argument as follows: This relation is a necessary condition for the existence of a strongly regular graph, but not a sufficient condition.

For instance, the quadruple (21,10,4,5) obeys this relation, but there does not exist a strongly regular graph with these parameters.

This shows that k is an eigenvalue of the adjacency matrix with the all-ones eigenvector.

The ij-th element of the left hand side gives the number of two-step paths from i to j.

The second term gives the number of two-step paths when i and j are directly connected.

Since the three cases are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive, the simple additive equality follows.

[10] Since the adjacency matrix A is symmetric, it follows that its eigenvectors are orthogonal.

: Eliminate x and rearrange to get a quadratic: This gives the two additional eigenvalues

[11] Following the terminology in much of the strongly regular graph literature, the larger eigenvalue is called r with multiplicity f and the smaller one is called s with multiplicity g. Since the sum of all the eigenvalues is the trace of the adjacency matrix, which is zero in this case, the respective multiplicities f and g can be calculated: As the multiplicities must be integers, their expressions provide further constraints on the values of v, k, μ, and λ.

Further, in this case, v must equal the sum of two squares, related to the Bruck–Ryser–Chowla theorem.

Further properties of the eigenvalues and their multiplicities are:[12] If the above condition(s) are violated for any set of parameters, then there exists no strongly regular graph for those parameters.

In 1960, Alan Hoffman and Robert Singleton examined those expressions when applied on Moore graphs that have λ = 0 and μ = 1.

Such graphs are free of triangles (otherwise λ would exceed zero) and quadrilaterals (otherwise μ would exceed 1), hence they have a girth (smallest cycle length) of 5.

Substituting the values of λ and μ in the equation

In turn: The Hoffman-Singleton theorem states that there are no strongly regular girth-5 Moore graphs except the ones listed above.