Structural functionalism

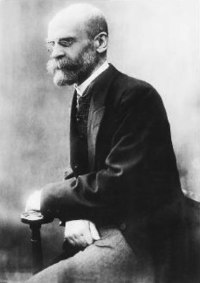

1800s: Martineau · Tocqueville · Marx · Spencer · Le Bon · Ward · Pareto · Tönnies · Veblen · Simmel · Durkheim · Addams · Mead · Weber · Du Bois · Mannheim · Elias Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability".

[3] In the most basic terms, it simply emphasizes "the effort to impute, as rigorously as possible, to each feature, custom, or practice, its effect on the functioning of a supposedly stable, cohesive system".

Durkheim used the term mechanical solidarity to refer to these types of "social bonds, based on common sentiments and shared moral values, that are strong among members of pre-industrial societies".

[1] The central concern of structural functionalism may be regarded as a continuation of the Durkheimian task of explaining the apparent stability and internal cohesion needed by societies to endure over time.

[8] Structural functionalism also took on Malinowski's argument that the basic building block of society is the nuclear family,[8] and that the clan is an outgrowth, not vice versa.

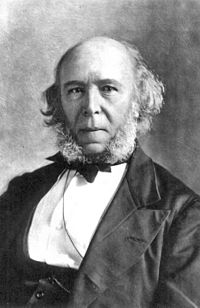

Comte suggests that sociology is the product of a three-stage development:[1] Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) was a British philosopher famous for applying the theory of natural selection to society.

[12] In fact, while Durkheim is widely considered the most important functionalist among positivist theorists, it is known that much of his analysis was culled from reading Spencer's work, especially his Principles of Sociology (1874–96).

[1] While reading Spencer's massive volumes can be tedious (long passages explicating the organic analogy, with reference to cells, simple organisms, animals, humans and society), there are some important insights that have quietly influenced many contemporary theorists, including Talcott Parsons, in his early work The Structure of Social Action (1937).

Spencer was not a determinist in the sense that he never said that In fact, he was in many ways a political sociologist,[12] and recognized that the degree of centralized and consolidated authority in a given polity could make or break its ability to adapt.

More specifically, Spencer recognized three functional needs or prerequisites that produce selection pressures: they are regulatory, operative (production) and distributive.

He argued that all societies need to solve problems of control and coordination, production of goods, services and ideas, and, finally, to find ways of distributing these resources.

The solution, as Spencer sees it, is to differentiate structures to fulfill more specialized functions; thus, a chief or "big man" emerges, soon followed by a group of lieutenants, and later kings and administrators.

Numerous critics have pointed out Parsons' underemphasis of political and monetary struggle, the basics of social change, and the by and large "manipulative" conduct unregulated by qualities and standards.

Kingsley Davis and Wilbert E. Moore (1945) gave an argument for social stratification based on the idea of "functional necessity" (also known as the Davis-Moore hypothesis).

They argue that the most difficult jobs in any society have the highest incomes in order to motivate individuals to fill the roles needed by the division of labour.

The argument also does not clearly establish why some positions are worth more than others, even when they benefit more people in society, e.g., teachers compared to athletes and movie stars.

In their attempt to explain the social stability of African "primitive" stateless societies where they undertook their fieldwork, Evans-Pritchard (1940) and Meyer Fortes (1945) argued that the Tallensi and the Nuer were primarily organized around unilineal descent groups.

Such groups are characterized by common purposes, such as administering property or defending against attacks; they form a permanent social structure that persists well beyond the lifespan of their members.

Status distinctions did not depend on descent, and genealogies were too short to account for social solidarity through identification with a common ancestor.

In particular, the phenomenon of cognatic (or bilateral) kinship posed a serious problem to the proposition that descent groups are the primary element behind the social structures of "primitive" societies.

"[26] Biological functionalism is an anthropological paradigm, asserting that all social institutions, beliefs, values and practices serve to address pragmatic concerns.

[29] By that fact, biological functionalism maintains that our individual survival and health is the driving provocation of actions, and that the importance of social rigidity is negligible.

Although the actions of humans without doubt do not always engender positive results for the individual, a biological functionalist would argue that the intention was still self-preservation, albeit unsuccessful.

There are, however, signs of an incipient revival, as functionalist claims have recently been bolstered by developments in multilevel selection theory and in empirical research on how groups solve social dilemmas.

Recent developments in evolutionary theory—especially by biologist David Sloan Wilson and anthropologists Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson—have provided strong support for structural functionalism in the form of multilevel selection theory.

"[37] Stronger criticisms include the epistemological argument that functionalism is tautologous, that is, it attempts to account for the development of social institutions solely through recourse to the effects that are attributed to them, and thereby explains the two circularly.

Anthony Giddens argues that functionalist explanations may all be rewritten as historical accounts of individual human actions and consequences (see Structuration).

[23] Gouldner thought that Parsons' theory specifically was an expression of the dominant interests of welfare capitalism, that it justified institutions with reference to the function they fulfill for society.

This critique focuses on exposing the danger that grand theory can pose when not seen as a limited perspective, as one way of understanding society.

[citation needed] Jeffrey Alexander (1985) sees functionalism as a broad school rather than a specific method or system, such as Parsons, who is capable of taking equilibrium (stability) as a reference-point rather than assumption and treats structural differentiation as a major form of social change.