Analogical models

A simple type of analogy is one that is based on shared properties;[1][2] and analogizing is the process of representing information about a particular subject (the analogue or source system) by another particular subject (the target system),[3] in order "to illustrate some particular aspect (or clarify selected attributes) of the primary domain".

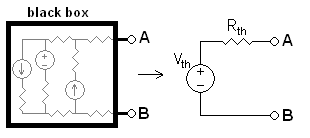

Analog devices are therefore those in which may differ in substance or structure but share properties of dynamic behaviour (Truit and Rogers, p. 1-3).

Once the calibration has taken place, modellers speak of a one-to-one correspondence in behaviour between the primary system and its analog.

Doing so preserves the correct energy flow between domains, a useful feature when modelling a system as an integrated whole.

[8] The earliest such analogy is due to James Clerk Maxwell who, in 1873, associated mechanical force with electrical voltage.

The power conjugate of voltage is electric current which, in the Maxwell analogy, maps to mechanical velocity.

Firestone's analogy has the advantage of preserving the topology of element connections when converting between domains.

[14] Maxwell's analogy was initially used merely to help explain electrical phenomena in more familiar mechanical terms.

It was also necessary to have the mechanical parts, the transducers, and the electrical components of the circuit analyzed as a complete system in order to predict the overall response of the filter.

The product of these is not in units of power and the ratio, known as magnetic reluctance, does not measure the rate of dissipation of energy so is not a true impedance.

For instance, because much of the theory of dynamical analogies arose from electrical theory the power conjugate variables are sometimes called V-type and I-type according to whether they are analogs of voltage or current respectively in the electrical domain.

Electronic circuits were used to model and simulate engineering systems such as aeroplanes and nuclear power plants before digital computers became widely available with fast enough turn over times to be practically useful.

Examples are Vogel and Ewel who published 'An Electrical Analog of a Trophic Pyramid' (1972, Chpt 11, pp.

105–121), Elmore and Sands (1949) who published circuits devised for research in nuclear physics and the study of fast electrical transients done under the Manhattan Project (however no circuits having application to weapon technology were included for security reasons), and Howard T. Odum (1994) who published circuits devised to analogically model ecological-economic systems at many scales of the geobiosphere.

We seem to assume that the process of constructing analogical models gives us access to the fundamental laws governing the target system.

However strictly speaking we only have empirical knowledge of the laws that hold true for the analogical system, and if the time constant for the target system is larger than the life cycle of human being (as in the case of the geobiosphere) it is therefore very difficult for any single human to empirically verify the validity of the extension of the laws of their model to the target system in their lifetime.