Bird collections

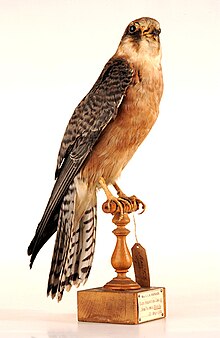

Collections may include a variety of preparation types emphasizing preservation of feathers, skeletons, soft tissues, or (increasingly) some combination thereof.

The roots of modern bird collections are found in the 18th- and 19th-century explorations of Europeans intent on documenting global plant and animal diversity.

[3] Early scientific bird collections included those belonging to Pallas and Naumann in Germany, Latham and Tunstall in England and Adanson in France.

Early specimens from Captain Cook's voyages as well as those described by Latham in his General Synopsis of Birds (1781–1785) were also lost possibly due to poor preservation technique.

The oldest surviving bird specimens include an African grey parrot once owned by Frances Teresa Stuart (1647–1702) that was buried with its owner in London’s Westminster Abbey.

However, the world's bird collections have been argued to be inadequate in documenting avian diversity, from taxonomic, geographic, and temporal perspectives, with some parts of tropical regions considered under-represented in particular museums.

These were further improved in the 17th century and a range of preservatives included ash (potassium carbonate), salt, sulphur, alum, alcohol and various plant extracts were used.

During this time, Comte de Reaumur at the Paris Museum had managed to find techniques to preserve specimens dry and without loss of colour.

[16][17] This technique was however a secret and similar results were later achieved by pickling using salt, ground pepper and alum and drying for a month with threads holding the bird in a natural position.

[3] The use of arsenic to preserve specimens was first introduced by Jean-Baptiste Bécoeur (1718-1777) but this method was publicly revealed only in 1800 by Louis Dufresne in Daudin's Traité Élémentaire et Complet d’Ornithologie (1800).

This and other important information, such as mass, sex, fat deposition, and degree of skull ossification, is written on a label along with a unique field and museum number.

All biological species including those of birds are represented by a holotype, the vast majority of which are full specimens (mostly skins) and in modern times explicitly designated in the original description of the taxon.

[29][30] In addition to taxonomic research, collections can provide information relevant to the study of variety of other ornithological questions, including comparative anatomy, ecology, behavior, disease, and conservation.

Bird collections offer the potential for current and future researchers to make in-depth morphological and molecular study of past avian diversity.

[35][36][37] The ornithologists who collected the eggs could never have known that their work would one day help establish causes for declines and help in making conservation strategies to save bird such as peregrine falcons from possible extinction.

As threats to bird populations grow and extinctions continue, historical specimens are valuable in documenting the impacts of human activities and causes of decline for threatened species.

A study of soot deposits on specimens collected within the United States Manufacturing Belt was used to track concentrations of atmospheric black carbon over a 135-year span.

Finally, at a time of rampant deforestation and species extinctions, scientists and conservationists should take the lead in providing an example to local people not to kill or hunt birds.

[28] Although taking small blood samples from wild birds is often viewed as a harmless alternative to collecting, it reduces survival by as much as 33%[50] and does not provide the benefits of a voucher specimen.