Subutai

Stephen Pow and Jingjing Liao note that "...the sense of irony conjured by imagining that the Mongol Empire’s greatest general was a reindeer-herding outsider to steppe nomadic culture has a strong literary appeal to modern authors.

Supposedly the Mongol army had destroyed his left wing, and nearly broken his center and captured him, until reinforcements from his son arrived and the battlefield turned dark.

[19] Because of this battle, Mohammed was unable to take advantage of the upheaval in the Kara-Khitai Empire (simultaneously being conquered by the Mongolian general Jebe), like he had in earlier wars.

As a result, the several hundred thousand man Khwarezm forces in reserve remained divided and were easily destroyed piecemeal by Genghis Khan's main army.

[21] Drained by the fierce pursuit, Mohammed fell ill and died at a fishing village on an island in the Caspian Sea in early 1221, an ignominious end for the man who styled himself the 'Second Alexander'.

Subutai and Jebe spent part of the 1219 winter in Azerbaijan and Iran, raiding and looting while preventing the western Khwarezm forces from assisting the rest of the empire to the east.

Here he conceived the idea of conducting the most audacious reconnaissance-in-force in history, which was described by Edward Gibbon as [an expedition] "which has never been attempted, and has never been repeated": 20,000 Mongol forces would circle the Caspian Sea through the Caucasus Mountains to fall on the rear of the Wild Kipchaks and Cumans.

Though the king George IV of Georgia was reluctant to commit to battle, Subutai and Jebe forced his hand by ravaging the countryside and killing his people.

In late 1211 he was the first to scale the walls of the key fortress of Huan-Chou, and took part in the ambush of a major Jin army at Wu Sha Pao and the climactic battle of Yehuling.

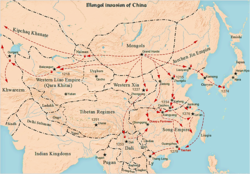

While Genghis invaded the Xi Xia by a more traditional northern route, Subutai unexpectedly attacked from the west over the mountains and inhospitable deserts in modern Turkestan, causing Tangut resistance to collapse.

Subutai had originally been assigned to conquer the Kipchak Turks in central Russia in 1229,[29] but was hurriedly recalled to China in 1229–1230 after the Mongol general Doqolqu suffered a major defeat.

At the Battle of Daohuigu, Subutai initially attempted to outflank the Jin by feinting an attack at the fortified location of Weizhou and maneuvering through an unguarded side corridor.

[31] In 1231–1232 Subutai made another attempt to outmaneuver the Jin fortified lines by using a similar highly audacious approach that they had employed in Khwarezm (1219) and Xi Xia (1226).

[34] Rather than continually attempting to attack the vigilant Jin during their retreat, Subutai instead dispersed his army into several detachments to target supplies in the area.

Additionally, the Jin began to employ a cutting edge gunpowder weapon called "Thunder Crash Bombs", which made it very difficult for the Mongols to get close enough for more concentrated fire.

After cutting off Kaifeng from any outside help, Subutai alternated intense bombardments using a mixture of Muslim trebuchets, mangonels, and captured gunpowder with periods of rest and plundering the countryside.

While Batu Khan, son of Jochi, was the overall leader, Subutai was the actual commander in the field, and as such was present in both the northern and southern campaigns against Kievan Rus'.

Though the Hungarian King Bela IV had effectively blocked the Carpathian passes using felled trees, ditches, traps, and other natural obstacles, in addition to the general disrepair or simple nonexistence of roads in eastern Hungary, Subutai's force still managed an astonishing pace of 100 km (60 mi) a day despite several feet of snow.

[46] In one stroke, the bulk of Hungarian fighting men were totally destroyed, but Mongol casualties in the center had been higher than normal: in addition to anywhere from many hundreds to many thousands of regular soldiers, Batu lost 30 of his 4,000 strong ba'aaturs (heavily armored bodyguards) and one of his lieutenants (Bagatu/Bakatu), which caused tension later in the camp.

From Rogerius' writings it would seem that scattered resistance by the peasantry was attempted, but it never really got off the ground, perhaps in part due to the flat open plains of central Hungary allowing scant opportunity for ambush or withdrawal.

After the defeat of the Hungarians at Mohi, Subutai used a stolen royal seal to issue bogus decrees across the country, leaving many unassuming inhabitants at his mercy.

A light cavalry force under Kadan was sent to chase King Bela along the Adriatic Coast, while the main army with its siege engines under Subutai and Batu attempted to pacify Hungary proper.

By early 1242, Subutai was discussing plans to invade the Holy Roman Empire, when news came of the death of Ögedei Khan and a revolt by the Cumans in Russia.

Subutai returned to Mongolia from the Song campaign in 1248 and spent the remainder of his life at his home in the vicinity of the Tuul River (near modern Ulaanbaatar), dying there at the age of 72.

Aju fought with his father, and then later led the successful five-year Mongol siege of the pivotal dual fortress of Xiangyang-Fancheng in the battle of Xiangyang, which opened up a gateway into the heart of the Song and enabled their total conquest six years later in 1279.

Trusted commander and retainer of Chinggis, later highly respected servant of Ogodei and Guyuk, Subotei served with great distinction in every phase of Mongolian national development during the first four decades of empire.

In his old age, Subotei saw a mighty dominion stretching from the borders of Hungary to the Sea of Japan, from the outskirts of Novgorod to the Persian Gulf and the Yangtze River.

In a unique historical anomaly, the strategic and operational innovations of Genghis Khan and Subutai became lost in history, and others were forced to rediscover them 600 and 700 years later.

Even though Subutai had devastated the armies of Russia, Georgia, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, and Latin Constantinople in a series of one-sided campaigns, Western military leaders, historians, and theorists completely ignored him until the 20th century.

Like Napoleon, Subutai (and Genghis Khan) would disperse their forces along a wide frontage and rapidly coalesce at decisive points to defeat the enemy in detail.