Subfossil lemur

The subfossil sites found around most of the island demonstrate that most giant lemurs had wide distributions and that ranges of living species have contracted significantly since the arrival of humans.

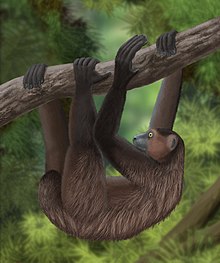

They also had many distinct traits among lemurs, including a tendency to rely on terrestrial locomotion, slow climbing, and suspension instead of leaping, as well as a greater dependence on leaf-eating and seed predation.

[8] They had shorter, more robust limbs, heavily built axial skeletons (trunks), and large heads[10] and are thought to have shared the common lemur trait of low basal metabolic rates, making them slow-moving.

[4] Their characteristic curved finger and toe bones (phalanges) suggest slow suspensory movement, similar to that of an orangutan or a loris, making them some of the most specialized mammals for suspension.

[8][9][12] Dental wear analysis has shed some light on this dietary mystery, suggesting that monkey lemurs had a more eclectic diet, while using tough seeds as a fall-back food item.

[8] These shared features suggest a similar lifestyle and diet, focused on percussive foraging (tapping with the skinny digit and listening for reverberation from hollow spots) of defended resources, such as hard nuts and invertebrate larvae concealed inside decaying wood.

[8] Daubentonia madagascariensis †Daubentonia robusta †Megaladapis edwardsi †Megaladapis grandidieri †Megaladapis madagascariensis †Pachylemur insignis †Pachylemur jullyi Varecia Lemur, Hapalemur, & Prolemur Eulemur Cheirogaleidae (Allocebus, Phaner, Cheirogaleus, Mirza, & Microcebus) Lepilemur †Archaeolemur majori †Archaeolemur edwardsi †Hadropithecus stenognathus †Mesopropithecus pithecoides †Mesopropithecus globiceps †Mesopropithecus dolichobrachion †Babakotia radofilai †Palaeopropithecus maximus †Palaeopropithecus ingens †Palaeopropithecus kelyus †Archaeoindris fontoynontii Indriidae (Propithecus, Avahi, & Indri) Subfossil sites in Madagascar have yielded the remains of more than just extinct lemurs.

[6] Even the greater bamboo lemur, a critically endangered species restricted to a small portion of the south-central eastern rainforest, has undergone significant range contraction since the mid-Holocene,[6][21] with subfossil remains from Ankarana Massif in the far north of Madagascar dating to 2565 BCE ± 70 years.

[23] As a group, the lemurs of Madagascar are extremely diverse, having evolved in isolation and radiated over the past 40 to 60 million years to fill many ecological niches normally occupied by other primates.

[8][25] The diets of most subfossil lemurs, most notably Palaeopropithecus and Megaladapis, consisted primarily of C3 plants, which use a form of photosynthesis that results in higher water loss through transpiration.

Seed dispersal biology is known for very few species in the spiny forest, including genera of plants suspected of depending on giant lemurs, such as Adansonia, Cedrelopsis, Commiphora, Delonix, Diospyros, Grewia, Pachypodium, Salvadora, Strychnos, and Tamarindus.

For example, Delonix has edible pods that are rich in protein, and Adansonia fruits have a nutritious pulp and large seeds that may have been dispersed by Archaeolemur majori or Pachylemur insignis.

[15] His discoveries in various marshes of central and southwestern Madagascar sparked paleontological interest,[12] resulting in an overabundance of taxonomic names and confused assemblages of bones from numerous species, including non-primates.

[15] One reconstruction of the confounded subfossil remains by paleontologist Herbert F. Standing depicted Palaeopropithecus as an aquatic animal that swam near the surface, keeping its eyes, ears, and nostrils slightly above water.

More recently, electron microscopy has allowed researchers to study behavioral patterns, and DNA amplification has helped with genetic tests that determine the phylogenetic relationships between the extinct and living lemurs.

[15] A new genus of sloth lemur, Babakotia, was discovered in 1986 by a team led by Elwyn L. Simons of Duke University in karst caves on the Ankarana Massif in northern Madagascar.

Consequently, it is impossible to know what percentage of lemur taxa were recently lost there; studies of Malagasy customs (ethnohistory) along with archaeological evidence suggests the eastern rainforests were more ecologically disturbed in the past than they are today.

[15] Comparisons of species counts from subfossil deposits and remnant populations in neighboring Special Reserves has further demonstrated decreased diversity in lemur communities and contracted geographic ranges.

Based on this evidence from Taolambiby in the southwest interior, as well as other dates for human-modified dwarf hippo bones and introduced plant pollen from other parts of the island, the arrival of humans is conservatively estimated at 350 BCE.

[22] The humid forests of the lower interior of the island were the last to be settled (as shown by the presence of charcoal particles), possibly due to the prevalence of human diseases, such as plague, malaria, and dysentery.

[15][34][39] The first was proposed in 1927 when Henri Humbert and other botanists working in Madagascar suspected that human-introduced fire and uncontrolled burning intended to create pasture and fields for crops transformed the habitats quickly across the island.

[15][34][41] Paul S. Martin applied his overkill hypothesis or "blitzkrieg" model to explain the loss of the Malagasy megafauna in 1984, predicting a rapid die-off as humans spread in a wave across the island, hunting the large species to extinction.

[15][34][35] Finally, in 1999, David Burney proposed that the complete set of human impacts worked together, in some cases along with natural climate change, and very slowly (i.e., on a time scale of centuries to millennia) brought about the demise of the giant subfossil lemurs and other recently extinct endemic wildlife.

Archeological evidence for butchery of giant subfossil lemurs, including Palaeopropithecus ingens and Pachylemur insignis, was found on specimens from two sites in southwestern Madagascar, Taolambiby and Tsirave.

[17][44] The most widespread and adaptable species, such as Archaeolemur, were able to survive despite hunting pressure and human-caused habitat change until human population growth and other factors reached a tipping point, cumulatively resulting in their extinction.

[33] The loss of grazers and browsers might have resulted in the accumulation of excessive plant material and litter, promoting more frequent and destructive wildfires, which would explain the rise in charcoal particles following the decline in coprophilous fungus spores.

Today, small fragments stand isolated among vast expanses of human-created savanna, despite an average annual rainfall that is sufficient to sustain the evergreen forests once found there.

[26] In 1995, a research team led by David Burney and Ramilisonina performed interviews in and around Belo sur Mer, including Ambararata and Antsira, to find subfossil megafaunal sites used early in the century by other paleontologists.

[48] Another interviewee, François, a middle-aged woodcutter who spent time in the forests inland (east) from the main road between Morondava and Belo sur Mer, and five of his friends, reported seeing kidoky recently.

The authors did not feel comfortable with such a dismissal because of their careful quizzing and use of unlabeled color plates during the interviews and because of the competence demonstrated by the interviewees in regards to local wildlife and lemur habits.