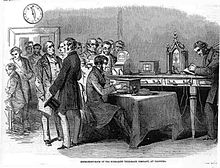

Submarine Telegraph Company

[citation needed] In 1847, the Bretts obtained a concession from the French government to lay and operate a submarine telegraph cable across the Channel.

[1] A proof of principle was conducted in 1849 by Charles Vincent Walker of the South Eastern Railway using gutta-percha insulated cable.

Gutta-percha, recently introduced by William Montgomerie for making medical equipment, was a natural rubber that was found to be ideal for insulating ocean cables.

Walker laid two miles (3.2 km) of the cable from the ship Princess Clementine off the coast of Folkestone.

Goliath transported the cable from the manufacturing plant in Greenwich to Dover in short lengths which were then spliced together onto a single drum.

Unattended cable suffered from the attentions of souvenir hunters who cut off pieces, or stripped the insulation to confirm to themselves that there was copper inside.

Dispersion was a problem not fully solved on submarine cables until loading started to be used at the beginning of the 20th century.

Initial reports stated that cable was damaged where it passed over rocks near Cap Gris Nez, but later French fishermen were blamed.

A story circulated much later (from 1865) that the fisherman who initially cut the cable thought it was a new species of seaweed with gold in its centre.

The largest investor was railway engineer Thomas Russell Crampton, who was put in charge of ordering the new cable.

The core of the new cable, again made by the Gutta Percha Company, was to have four conductors, substantially increasing the potential traffic, and insulated with gutta-percha as before.

This task was given to a wire-rope making company, Wilkins and Wetherly, who armoured the cable with an outer layer of helically laid iron wires.

The issue was resolved by allowing Newall to take over production of the cable at Wilkins and Wetherly's Wapping premises.

There was no easy access and the adjacent business refused permission to cross their property, thinking that electrical apparatus would invalidate their fire insurance.

However, a neighbouring business granted access, but the cable still had to be manually hauled to a wharf on the River Thames.

This was a difficult task which had to frequently be halted to tie back protruding broken iron wires.

At the River Thames, the cable was loaded on to the Blazer, a hulk loaned to the Submarine Telegraph Company by the government.

[15] They arrived a day late and missed their rendezvous with HMS Widgeon which was tasked with making the splice at sea.

[18] The opening had again missed the French government deadline, but the concession was nevertheless renewed on 23 October for ten years from that date.