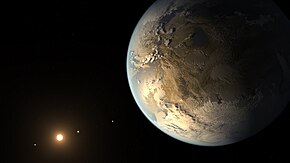

Superhabitable world

The concept was introduced in a 2014 paper by René Heller and John Armstrong, in which they criticized the language used in the search for habitable exoplanets and proposed clarifications.

[4] In 2020, astronomers, building on Heller and Armstrong's hypothesis, identified 24 potentially superhabitable exoplanets based on measured characteristics that fit these criteria.

[10] However, F-type stars emit large amounts of ultraviolet radiation, and without the presence of a protective ozone layer, could disrupt nucleic acid-based life on a planet's surface.

Due to the low luminosity of red dwarfs, the circumstellar habitable zone (HZ)[a] is in very close proximity to the star, which causes any planet to become tidally locked.

[3][16] Also nicknamed "Goldilocks stars," orange dwarfs emit low enough levels of ultraviolet radiation to eliminate the need for a protective ozone layer, but just enough to contribute to necessary biological processes.

[19] This necessity is based on the belief that as a planet or moon ages, it experiences increasing levels of biodiversity, since native species have had more time to evolve, adapt, and stabilize the environmental conditions suitable for life.

[32] Heller and Armstrong argue that the optimal mass and radius of a superhabitable world can be determined by geological activity; the more massive a planetary body, the longer time it will continuously generate internal heat—a major contributing factor to plate tectonics.

[33][29] An important geological process is plate tectonics, which appears to be common in terrestrial planets with a significant rotation speed and an internal heat source.

[34] If large bodies of water are present on a planet, plate tectonics can maintain high levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in its atmosphere and increase the global surface temperature through the greenhouse effect.

[35] However, if tectonic activity is not significant enough to increase temperatures above the freezing point of water, the planet could experience a permanent ice age, unless the process is offset by another energy source like tidal heating or stellar irradiation.

[22] A sufficiently strong magnetic field effectively shields a world's surface and atmosphere against ionizing radiation emanating from the interstellar medium and its host star.

[22] Less massive bodies and those that are tidally locked are likely to have a weak to non-existent magnetic field, which over time can result in the loss of a significant portion of its atmosphere by hydrodynamic escape and become a desert planet.

[44][45][46] For example, marine ecosystems found in the shallow areas of Earth's oceans and seas, given the amount of light and heat they receive, are observed to have greater biodiversity and are generally seen as being more comfortable for aquatic species.

[43][47] In general, the climate of a superhabitable planet would be warm, moist, and homogeneous, allowing life to extend across the surface without presenting large population differences.

[58] However, earlier research on Kepler-69c suggests that because its orbit lies near the inner edge of the HZ, its atmosphere could likely be in a runaway greenhouse state, which could heavily impact its prospects for habitability.