Susan Curtiss

[2] Her 1976 UCLA PhD dissertation[3] centered on the study of the grammatical development of Genie, a famous feral child.

After receiving her PhD, she continued to study critical periods, modularity, and grammatical development at UCLA.

[11] In November 1970, the child welfare authorities of Los Angeles discovered a young girl who had been subject to extreme isolation and abuse.

When Genie was admitted to the hospital, at the age of 13 years and 7 months, doctors concluded that she had not acquired a first language.

[13] Curtiss, specifically, set out to teach Genie the difference between singular and plural count nouns.

Curtiss and her research team found that despite Genie’s limited acquisition of syntax, she had relatively advanced cognitive abilities.

Curtiss observed isolated incidents in which she believed Genie showed evidence of using recursion, a complex feature of human language.

[16] Curtiss and her team determined that Genie was most likely right-handed, but on dichotic listening tests they discovered that Genie, unlike most right-handed people, was right-hemisphere dominant for language; she had normal results for environmental sounds, proving that her brain was not simply reversed in dominance for language.

In 1977, Academic Press published her thesis as a book titled Genie: A Psycholinguistic Study of A Modern-Day “Wild Child.

She further accused Rigler and Curtiss of disregarding data from the two months Ruch’s own home as it did not align with the goals of their research.

Jay Shurley and David Elkind, who were involved in the early phases of Genie's case study, left the research team over these concerns.

[11][21] Additionally, people believe that members of the research team took on too many roles in an attempt to study, befriend, and parent Genie.

As the case study of Genie demonstrated, reaching puberty without having had significant exposure to language does not mean that an individual will be unable to communicate for the remainder of their life.

[13] In 1980, Curtiss began research on a woman who was given the pseudonym “Chelsea.” Chelsea, 32, had been born deaf, but in childhood was not diagnosed as such.

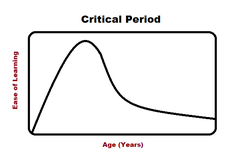

[22] Curtiss compares Genie and Chelsea, offering both cases as supporting evidence for a critical period for syntax.

Neither of these two individuals had significant exposure to language prior to reaching puberty, and despite attempts to teach them English, neither of them was able to grasp syntax.

Curtiss notes that Genie was able to grasp certain facets of the English language, such as phrasal categories, whereas Chelsea was only able to enlarge her lexicon and understand discourse.

[22] Curtiss has also done research on the modularity of grammar, exploring syntax and semantics are separate faculties of human language.

In pursuit of this, Curtiss has conducted research on children who show evidence of dissociating different faculties of language from one another.

Antony, a mentally retarded 6 year old, was able to produce syntactically well-formed sentences, but they were semantically incorrect.

From an early age she showed strength regarding the syntactic and morphological features of language, but her speech was frequently neither semantically correct nor fully intelligible.

[24][23] These cases serve as evidence supporting Curtiss's commitment to the modularity of syntactic and semantic faculties.

These data supported Curtiss's belief that syntax was preserved to a greater degree than semantics in Alzheimer's patients.

[26] Curtiss also determined that the number of errors made by each Alzheimer's patient correlated with the severity of the disease.

[27] Another test, the CYCLE-N (Curtiss Yamada Comprehensive Language Evaluation—Neurological), was designed specifically for adults and for mapping grammar in the brain.