Sati (practice)

[6] Although it is debated whether it received scriptural mention in early Hinduism,[7] it has been linked to related Hindu practices in the Indo-Aryan-speaking regions of India, which have diminished the rights of women, especially those to the inheritance of property.

[33] In later centuries, the text was cited as the origin of Sati, with a variant reading allowing the authorities to insist that the widow sacrifice herself in reality by joining her deceased husband on the funeral pyre.

[44] The practice of sati was emulated by those seeking to achieve high status of the royalty and the warriors as part of the process of Sanskritisation,[25] but its spread was also related to the centuries of Islamic invasion and its expansion in South Asia,[25][45][26][46] and to the hardship and marginalisation that widows endured.

[52] Daniel Grey states that the understanding of origins and spread of sati were distorted in the colonial era because of a concerted effort to push "problem Hindu" theories in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

[53] Lata Mani wrote that all of the parties during the British colonial era that debated the issue subscribed to the belief in a "golden age" of Indian women followed by a decline in concurrence to the Muslim conquests.

The Manimekalai similarly provides evidence that such practices existed in Tamil lands, and the Purananuru claims widows prefer to die with their husband due to the dangerous negative power associated with them.

Overall, both admiration and criticism of sati cut across cultural lines, with examples of support from Greeks, Muslims, and British individuals, and opposition from Hindus, dating back as far as the seventh century.

[91] Ralph Fitch noted in 1591:[92] When the husband died his wife is burned with him, if she be alive, if she will not, her head is shaven, and then is never any account made of her after.François Bernier (1620–1688) gave the following description: At Lahor I saw a most beautiful young widow sacrificed, who could not, I think, have been more than twelve years of age.

[114] He visited Kolkata's cremation grounds to persuade widows against immolation, formed watch groups to do the same, sought the support of other elite Bengali classes, and wrote and disseminated articles to show that it was not required by Hindu scripture.

[154] Inamdar, Oberfield and Darrell state that the women who commit sati are often "childless or old and face miserable impoverished lives" which combined with great stress from the loss of the only personal support may be the cause of a widow's suicide.

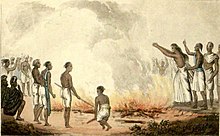

[163] Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a 17th-century world traveller and trader of gems, wrote that women were buried with their dead husbands along the Coast of Coromandel while people danced during the cremation rites.

Finally, from Bengal, where the tradition of the pyre held sway, the widow's feet could be tied to posts fixed to the ground, she was asked three times if she wished to ascend to heaven, before the flames were lit.

[168] Ram Mohan Roy observed that when women allow themselves to be consigned to the funeral pyre of a deceased husband it results not just "from religious prejudices only", but, "also from witnessing the distress in which widows of the same rank in life are involved, and the insults and slights to which they are daily subject.

For example, the ancient and sacred Atharvaveda, one of the four Vedas, believed to have been composed around 1000 BCE, describes a funerary ritual where the widow lies down by her deceased husband, but is then asked to ascend, to enjoy the blessings from the children and wealth left to her.

[173] There is only one mention in the Vedas, of a widow lying down beside her dead husband who is asked to leave the grieving and return to the living, then prayer is offered for a happy life for her with children and wealth.

Dehejia writes that this passage does not imply a pre-existing sati custom, nor of widow remarriage, nor that it is authentic verse; its solitary mention may also be explained as an insertion into the text at a latter date.

In Harlan's model, having made the holy vow to burn herself, the woman becomes a sativrata, existing in a transitional stage between the living and the dead called the Antarabhava before ascending the funeral pyre.

However, although the satimata's intentions are always for the good of the family, she is not averse to letting children become sick, or the cows' udders to wither, if she thinks this is an appropriate lesson to the living wife who has neglected her duties as pativrata.

In the Hindu scriptures, states David Brick, Sati is a wholly voluntary endeavor; it is not portrayed as an obligatory practice, nor does the application of physical coercion serve as a motivating factor in its lawful execution.

[202] There is only one mention in the Vedas, of a widow lying down beside her dead husband who is asked to leave the grieving and return to the living, then prayer is offered for a happy life for her with children and wealth.

Dehejia writes that this passage does not imply a pre-existing sati custom, nor of widow remarriage, nor that it is authentic verse; its solitary mention may also be explained as an insertion into the text at a latter date.

[202] Professor David Brick of the University of Michigan, in the paper ‘The Dharmasastric Debate on Widow Burning’, writes: There is no mention of sahagamana (sati) whatsoever in either Vedic literature or any of the early Dharmasutras or Dharmasastras.

However, this account is contradicted by the very next stanza found in all versions of the Mahabharata, which states that her dead body and that of her husband were handed over by sages to the Kaurava elders in Hastinapura for the funeral rites.

Burning herself on the pyre would give her and her husband, automatic, but not eternal, reception into heaven (svarga), whereas only the wholly chaste widow living out her natural lifespan could hope for final liberation (moksha) and the breaking the cycle of saṃsāric rebirth.

Indeed, after Vijnanesvara in the early twelfth century, the strongest position taken against sahagamana appears to be that it is an inferior option to brahmacarya (ascetic celibacy), since its result is only heaven rather than moksa (liberation).

Finally, in the third period, several commentators refute even this attenuated objection to sahagamana, for they cite a previously unquoted smrti passage that specifically lists liberation as a result of the rite's performance.

Death may grant a woman's wish to enter heaven with her dead husband, but living offers her the possibility of reaching moksha through knowledge of the self through learning, reflecting and meditating.

The 2005 novel The Ashram by Indian writer Sattar Memon, deals with the plight of an oppressed young woman in India, under pressure to commit sati and the endeavours of a western spiritual aspirant to save her.

[citation needed] In the U.S. version of fictional series The Office (season 3, episode 6) titled "Diwali", Michael Scott talks about Hindu culture with Kelly's parents, and asks specifically if her mother has to die with her husband.

[citation needed] Rudyard Kipling's poem The Last Suttee (1889) recounts how the widowed queen of a Rajput king disguised herself as a nautch girl in order to pass through a line of guards and die upon his pyre.