Suwa-taisha

The god of the Upper Shrine, named Takeminakata in the imperially-commissioned official histories, is also often popularly referred to as 'Suwa Myōjin' (諏訪明神), 'Suwa Daimyōjin' (諏訪大明神), or 'Suwa-no-Ōkami' (諏訪大神, 'Great Kami of Suwa').

[13][14][15][16] In a feudal Buddhist legend, this god is identified as a king from India whose feats included quelling a rebellion in his kingdom and defeating a dragon in Persia before manifesting in Japan as a native kami.

[17][18] In another feudal folk story, the god is said to have originally been a warrior named Kōga Saburō who returned from a journey into the underworld only to find himself transformed into a serpent or dragon.

The Nihon Shoki (720 CE) refers to envoys sent to worship "the wind-gods of Tatsuta and the gods of Suwa and Minochi in Shinano [Province]"[a] during the fifth year of the reign of Empress Jitō (691 CE),[1] which suggests that a notable kami in Suwa was already being worshiped by the imperial (Yamato) court as a water and/or wind deity during the late 7th century, on par with the wind gods of Tatsuta Shrine in Yamato Province (modern Nara Prefecture).

[35][36] Fune Kofun, a burial mound dating from the early 5th century discovered near the Kamisha Honmiya in 1959, yielded a number of important artifacts, among them weapons and implements of a ritual nature such as two dakōken (蛇行剣, a wave-bladed ceremonial sword).

The tomb's location and the nature of the grave goods suggest that the individuals buried therein were important personages perhaps connected in some way to what would become the Upper Shrine.

[37][38] Local historians have seen the legend that speaks of the Upper Shrine's deity as an intruding conqueror who wrested control of the Lake Suwa region from the native god Moriya (Moreya) to reflect the subjugation of local clans who controlled the area by invaders allied with the Yamato state - identified as the founders of the Upper Shrine's high priestly (大祝 Ōhōri) house - around the late 6th/early 7th centuries, with the appearance of burial mounds markedly different from the type exemplified by Fune Kofun heretofore common in the region around this time period being taken as the signs of Yamato expansion into Suwa,[37][39][40][41] though this idea has been called into question in recent years due to the myth's late (medieval) attestation and its similarity to stories concerning the conflict between Prince Shōtoku and Mononobe no Moriya that were in wide circulation during the Middle Ages.

[42][43][44] 'Takeminakata', the name by which the deity of the Upper Shrine is more commonly known to the imperial court, appears in the historical record for the first time in the Kojiki's (711-712 CE) kuni-yuzuri myth cycle.

[45][51] The national histories record Takeminakata's exceptionally rapid rise in importance: from rankless (无位), the imperial court steadily promoted the deity to increasingly higher ranks within the space of twenty-five years, beginning with junior fifth, upper grade (従五位上) in 842 CE.

The Kanasashi are thought to have been originally district magistrates (郡領 gunryō) in charge of producing and collecting taxed goods and laborers to be sent to the central government in Yamato Province.

The same title appears in a seal in the Lower Shrine's possession (designed as an Important Cultural Property in 1934) traditionally said to have been bequeathed by the Emperor Heizei (reigned 806-809).

[70] As Buddhism began to penetrate Suwa and syncretize with local beliefs, the deities of the Upper and Lower Shrines came to be identified with the bodhisattvas Samantabhadra (Fugen) and Avalokiteśvara (Kannon), respectively.

[71][72][32] Buddhist temples and other edifices (most of which belonged to the esoteric Shingon school) were erected on the precincts of both shrines, such as a sanctuary to Samantabhadra known as the Fugen-dō (普賢堂) and a stone pagoda symbolizing the legendary iron tower in India where, according to Shingon tradition, Nagarjuna was said to have received esoteric teachings from Vajrasattva (considered to be an aspect of Samantabhadra) called the Tettō (鉄塔 "iron tower").

[32] As Buddhist ethics, which opposed the taking of life and Mahayana's strict views on vegetarianism somewhat conflicted with Suwa Myōjin's status as a god of hunting, the Suwa cult devised elaborate theories that legitimized the hunting, eating, and sacrifice of animals such as deer (a beast sacred to the god) within a Buddhist framework.

[76] The shrines of Suwa and the priestly clans thereof flourished under the patronage of the Hōjō, which promoted devotion to the god as a sign of loyalty to the shogunate.

Second, the shogunate appointed major non-Shinano vassals to manors in the province, who then acted as sponsors and participants in the shrine rituals, eventually installing the cult in their native areas.

[80] A third factor was the exemption granted to the shrines of Suwa from the ban on falconry (takagari) - a favorite sport of the upper classes - imposed by the shogunate in 1212, due to the importance of hunting in its rites.

[84][85][86] Tokitsugu's son who inherited the priesthood, Yoritsugu (頼継), was stripped from his position and replaced by Fujisawa Masayori (藤沢政頼), who hailed from a cadet branch of the clan.

[90] To this end, he commissioned a set of ten illustrated scrolls (later expanded to twelve) showcasing the shrine's history and its various religious ceremonies, which was completed in 1356.

[96] After Yorishige's downfall, Suwa was divided between the Takeda and their ally, Takatō Yoritsugu (高遠頼継), who coveted the position of high priest.

[103][104] In 1582, the eldest son of Oda Nobunaga, Nobutada, led an army into Takeda-controlled Shinano and burned the Upper Shrine to the ground.

[100][101] The period saw escalating tensions between the priests and the shrine monks (shasō) of the Suwa complex, with increasing attempts from the priesthood to distance themselves from the Buddhist temples.

By the end of the Edo period, the priests, deeply influenced by Hirata Atsutane's nativist, anti-Buddhist teachings, became extremely antagonistic towards the shrine temples and their monks.

The shrines of Suwa, due to their prominent status as ichinomiya of Shinano, were chosen as one of the primary targets for the edict of separation, which took effect swiftly and thoroughly.

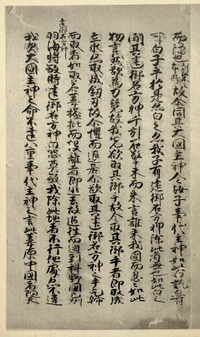

While a document purportedly dating from 1553 (but which may be a pseudepigraphical work of later provenance) states that the Upper Shrine "worships a mountain as its shintai" (以山為神体而拝之矣), it does not specifically identify this mountain to be Mount Moriya; indeed no source identifies Mount Moriya as the Upper Shrine's focus of worship before the Meiji period, when this identification first appeared and began to circulate.

This theory interprets the hei-haiden as being oriented towards the Upper Shrine's hunting grounds located at the Yatsugatake's foothills in what is now the town of Fujimi.

[122] As for the iwakura, there seems to be evidence based on old maps and illustrations of the Honmiya compound that the Suzuri-ishi was originally situated elsewhere before it was moved to its current location,[123] making its identification with the sacred rock found in ancient records doubtful.

An alternative theory proposes that the iwakura spoken of in these texts actually refers to a rock deep within the inner sanctum, over which the Tettō was erected.

[134] During the Middle Ages, the area around the Maemiya was known as the Gōbara (神原), the 'Field of the Deity', as it was both the residence of the Upper Shrine's Ōhōri and the site of many important rituals.

[135] The Ōhōri's original residence in the Gōbara, the Gōdono (神殿), also functioned as the political center of the region, with a small town (monzen-machi) developing around it.