Swahili people

In certain regions, such as Lamu Island, this differentiation is even more stratified in terms of societal grouping and dialect, hinting at the historical processes by which the Swahili have coalesced over time.

More recently, through a process of Swahilization, this identity extends to any person of African descent who speaks Swahili as their first language, is Muslim, and lives in a town of the main urban centres of most of modern-day Tanzania and coastal Kenya, northern Mozambique, or the Comoros.

Other, older dialects like Kimrima and Kitumbatu have far fewer Arabic loanwords, indicative of the language's fundamental Bantu nature.

Zanzibari traders' intensive push into the African interior from the late eighteenth century induced the adoption of Swahili as a common language throughout much of East Africa.

Archaeological finds at Fukuchani, on the northwest coast of Zanzibar, indicate a settled agricultural and fishing community from the 6th century CE at the latest.

The similarity to contemporary sites such as Mkokotoni and Dar es Salaam indicate a unified group of communities that developed into the first centre of coastal maritime culture.

These African migrants seem to have developed a concept of Shirazi origin as they moved further southwards, near Malindi and Mombasa, along the Mrima coast; the longstanding trade connections with the Persian gulf gave credence to these myths.

They moved south, founding mosques and introducing coinage and elaborately carved inscriptions and mihrabs; they should be interpreted as indigenous African Muslims who played the politics of the Middle East to their advantage.

One thesis, based on oral tradition, states that immigrants from the Shiraz region in southwestern Iran directly settled various mainland ports and islands on the eastern African seaboard beginning in the tenth century.

By 1200 CE, they had established local sultanates and mercantile networks on the islands of Kilwa, Mafia, and Comoros, along the Swahili coast, and in northwestern Madagascar.

[35] In 2022, DNA was extracted, analyzed, and compared in 80 samples taken from people buried between 1250 and 1800 CE in towns that were mostly along the Swahili Coast in modern Kenya and Tanzania.

[13][36] For centuries, the Swahili depended greatly on trade from the Indian Ocean, and they played an important role as middlemen between southeast, central, and southern Africa as well as the outside world.

[37] Trade routes extended from Kenya to Tanzania into modern-day Congo, along which goods were brought to the coasts and sold to Arab, Indian, and Portuguese traders.

Historical and archaeological records attest to Swahilis being prolific maritime merchants and sailors[38][39] who plied the southeast African coastline to lands as far away as Arabia,[40] Persia,[40] Madagascar,[38]: 110 India,[39][41] and China.

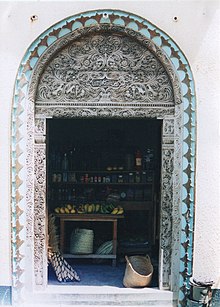

[45] Thought by many early scholars to be essentially of Arab or Persian style and origin, some contemporary academics have suggested that archaeological, written, linguistic, and cultural evidence might suggest an African genesis to Swahili architecture, which would be accompanied only later by enduring Arabic and Islamic influences in the form of trade and an exchange of ideas.

[48] Local architecture included arches, courtyards, isolated women's quarters, mihrab, towers, and decorative elements on the buildings themselves.