Swallowing

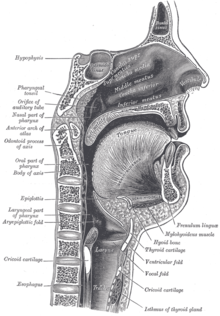

Swallowing, also called deglutition or inglutition[1] in scientific contexts, is the process in the body of a human that allows for a substance to pass from the mouth, to the pharynx, and into the esophagus, while shutting the epiglottis.

However, from the viewpoints of physiology, of speech–language pathology, and of health care for people with difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia), it is an interesting topic with extensive scientific literature.

The bolus is ready for swallowing when it is held together by saliva (largely mucus), sensed by the lingual nerve of the tongue (VII—chorda tympani and IX—lesser petrosal) (V3).

In order for anterior to posterior transit of the bolus to occur, orbicularis oris contracts and adducts the lips to form a tight seal of the oral cavity.

Next, the superior longitudinal muscle elevates the apex of the tongue to make contact with the hard palate and the bolus is propelled to the posterior portion of the oral cavity.

They are scattered over the base of the tongue, the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches, the tonsillar fossa, uvula and posterior pharyngeal wall.

In fact, it has been shown that the swallowing reflex can be initiated entirely by peripheral stimulation of the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve.

The palatopharyngeal folds on each side of the pharynx are brought close together through the superior constrictor muscles, so that only a small bolus can pass.

The adduction of the vocal cords is affected by the contraction of the lateral cricoarytenoids and the oblique and transverse arytenoids (all recurrent laryngeal nerve of vagus).

The clinical significance of this finding is that patients with a baseline of compromised lung function will, over a period of time, develop respiratory distress as a meal progresses.

Retroversion of the epiglottis, while not the primary mechanism of protecting the airway from laryngeal penetration and aspiration, acts to anatomically direct the food bolus laterally towards the piriform fossa.

This phase is passively controlled reflexively and involves cranial nerves V, X (vagus), XI (accessory) and XII (hypoglossal).

Swallowing becomes a great concern for the elderly since strokes and Alzheimer's disease can interfere with the autonomic nervous system.

Consultation with a dietician is essential, in order to ensure that the individual with dysphagia is able to consume sufficient calories and nutrients to maintain health.

In terminally ill patients, a failure of the reflex to swallow leads to a build-up of mucus or saliva in the throat and airways, producing a noise known as a death rattle (not to be confused with agonal respiration, which is an abnormal pattern of breathing due to cerebral ischemia or hypoxia).

In fish, the tongue is largely bony and much less mobile and getting the food to the back of the pharynx is helped by pumping water in its mouth and out of its gills.

In snakes, the work of swallowing is done by raking with the lower jaw until the prey is far enough back to be helped down by body undulations.