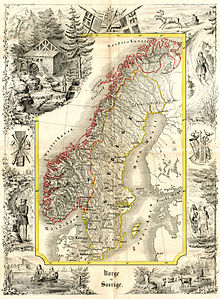

Sweden in Union with Norway

The Napoleonic Wars caused Finland to be separated from Sweden, and provided the chance to compensate for the loss by wresting Norway from the united kingdoms of Denmark-Norway.

Viewing the possibility of a joint Danish and French attack as the greater danger, king Gustav IV concentrated his army in southern Sweden and staged an invasion of Norway.

He refrained from pursuing the Swedish army beyond the border, while Sweden was hard pressed by the Russians in Finland, contrary to urgent requests from king Frederick VI.

On 5 June the duke regent (Gustav's uncle) Charles XIII was proclaimed king after accepting a new liberal constitution, which was ratified by the Riksdag the next day.

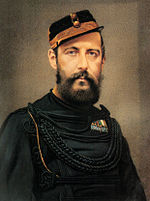

[1] Bernadotte, now crown prince Charles John or "Karl Johan", planned to acquire Norway by joining the enemies of Napoleon, whose only loyal ally was Denmark-Norway.

[1] These two treaties were, in effect, the cornerstones of a fresh coalition against Napoleon, and were confirmed on the outbreak of the Franco-Russian War by a conference between Alexander and Charles John at Turku on 30 August 1812, when the Tsar undertook to place an army corps of 35,000 men at the disposal of the Swedish crown prince for the conquest of Norway.

[1] The Treaty of Åbo, and indeed the whole of Charles John's foreign policy in 1812, provoked violent and justifiable criticism among the better class of politicians in Sweden.

The immorality of indemnifying Sweden at the expense of a weaker friendly power was obvious; and, while Finland was now definitively sacrificed, Norway had still to be won.

[1] Moreover, the United Kingdom and Russia insisted that Charles John's first duty was to the anti-Napoleonic coalition, the former power vigorously objecting to the expenditure of her subsidies on the nefarious Norwegian adventure before the common enemy had been crushed.

Only on his very ungracious compliance did the United Kingdom also promise to countenance the union of Norway and Sweden (Treaty of Stockholm, 3 March 1813), and on 23 April, Russia gave her guarantee to the same effect.

[1] The Swedish crown prince rendered several important services to the allies during the campaign of 1813 but after the Battle of Leipzig (1813) went his own way, determined to cripple Denmark and secure Norway at all costs.

These terms were formalized and signed at the Treaty of Kiel on 14 January, in which Denmark negotiated to maintain sovereignty over the Norwegian possessions of Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland.

Already in Norway, the viceroy, Hereditary Prince Christian Frederik resolved to preserve the integrity of the country, and if possible the union with Denmark, by taking the lead in a Norwegian insurrection.

When crown prince Charles John returned from the final battles against France, he launched an attack on the outnumbered Norwegian army on 29 July.

Christian Frederik succeeded in excluding from the text any indication that Norway had recognized the Treaty of Kiel, and Sweden accepted that it was not to be considered a premise of the future union between the two states.

Understanding the advantage of avoiding a costly war and of letting Norway enter into a union voluntarily instead of being annexed as a conquered territory, Charles John offered favorable peace terms.

He would then transfer his executive powers to the elected representatives of the people, who would negotiate the terms of the union with Sweden, and finally relinquish all claims to the Norwegian throne and leave the country.

The new king devoted himself to the promotion of the material development of the country, with the Göta Canal absorbing the greater portion of the twenty-four million the Riksdaler voted for the purpose.

[1] The popularity of Charles XIV decreased for a time in the 1830s, culminating in the Rabulist riots in 1838 after the Lèse-majesté conviction of the journalist Magnus Jacob Crusenstolpe, and some calls for his abdication.

During the Crimean War Sweden remained neutral, although public opinion was decidedly anti-Russian, and sundry politicians regarded the conjuncture as favorable for regaining Finland.

[1] The relations with Norway during the reign of King Oscar II had great influence on political life in Sweden, and more than once it seemed as if the union between the two countries was on the point of being wrecked.

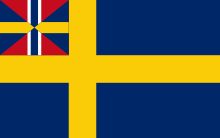

However, when the Norwegian Storting, for the third time, passed a bill for a national or "pure" flag, which King Oscar eventually sanctioned, Count Douglas resigned in his turn and was succeeded by the Swedish minister at Berlin, Lagerheim, who managed to pilot the questions of the union into more quiet waters.

On the other hand, ex-Professor E. Carlson, of the Gothenburg University, succeeded in forming a party of Liberals and Radicals to the number of about 90 members, who besides being in favor of the extension of the franchise, advocated the full equality of Norway with Sweden in the management of foreign affairs.

[1] The result of the negotiations was published in a so-called "communiqué", dated 24 March 1903, in which, among other things, it was proposed that the relations of the separate consuls to the joint ministry of foreign affairs and the embassies should be arranged by identical laws, which could not be altered or repealed without the consent of the governments of both countries.

All efforts to solve the consular question by itself had failed, but it was considered that an attempt might be made to establish separate consuls in combination with a joint administration of diplomatic affairs on a full unionistic basis.

[1] Crown Prince Gustaf, who during the illness of King Oscar II was appointed regent, took the initiative of renewing the negotiations between the two countries, and on 5 April in a combined Swedish and Norwegian Council of State made a proposal for a reform both of the administration of diplomatic affairs and of the consular service on the basis of full equality between the two kingdoms, with the express reservation, however, of a joint foreign minister – Swedish or Norwegian – as a condition for the existence of the union.

In order that no obstacles should be placed in the way for renewed negotiations, Erik Gustaf Boström, the Prime Minister, resigned and was succeeded by Johan Ramstedt.

On 23 September the delegates came to an agreement, the principal points of which were: that such disputes between the two countries which could not be settled by direct diplomatic negotiations, and which did not affect the vital interests of either country, should be referred to the permanent court of arbitration at The Hague, that on either side of the southern frontier a neutral zone of about fifteen kilometers width should be established, and that within eight months the fortifications within the Norwegian part of the zone should be destroyed.

Other clauses dealt with the rights of the Sami people to graze their reindeer alternatively in either country, and with the question of transport of goods across the frontier by rail or other means of communication, so that the traffic should not be hampered by any import or export, prohibitions or otherwise.