Swedish emigration to the United States

The emphasis shifted from religion to politics in the 19th century, when liberal citizens of the hierarchic Swedish class society looked with admiration to the American Republicanism and civil rights.

[9] Akenson argues that hard times in Sweden before 1867 produced a strong push effect, but that for cultural reasons most Swedes refused to emigrate and clung on at home.

From the Swedish port towns of Stockholm, Malmö and Gothenburg, transport companies operated various routes, some of them with complex early stages and consequently a long and trying journey on the road and at sea.

The majority of Swedish emigrants, however, travelled from Gothenburg to Hull, UK, on dedicated boats run by the Wilson Line, then by train across Britain to Liverpool and the big ships.

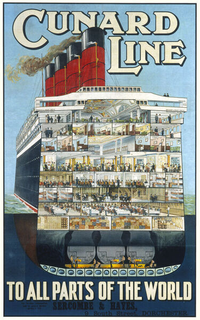

Propaganda and advertising by shipping line agents was often blamed for emigration by the conservative Swedish ruling class, which grew increasingly alarmed at seeing the agricultural labor force leave the country.

It was a Swedish 19th-century cliché to blame the falling ticket prices and the pro-emigration propaganda of the transport system for the craze of emigration, but modern historians have varying views about the real importance of such factors.

[19] The research of Brattne and Åkerman has shown that the leaflets sent out by the shipping line agents to prospective emigrants would not so much celebrate conditions in the New World, as simply emphasize the comforts and advantages of the particular company.

This small group founded a settlement they named New Upsala in Waukesha County, Wisconsin, and began to clear the wilderness, full of enthusiasm for frontier life in "one of the most beautiful valleys the world can offer".

The American Midwest was an agricultural antipode to Småland, for it, Unonius reported in 1842, "more closely than any other country in the world approaches the ideal which nature seems to have intended for the happiness and comfort of humanity.

[29] Lutherans such as Lars Paul Esbjörn – influenced by Pietism and Methodism and felt he was denied advancement in the church because of it – also found new opportunities in the United States.

[39] "Yes, emigration is indeed a 'mania'", wrote the liberal Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning sarcastically, "The mania of wanting to eat one's fill after one has worked oneself hungry!

The great majority of them had been peasants in the old country, pushed away from Sweden by disastrous crop failures[44] and pulled towards the United States by the cheap land resulting from the 1862 Homestead Act.

At the height of migration, familial America-letters could lead to chain reactions which would all but depopulate some Swedish parishes, dissolving tightly knit communities which then re-assembled in the Midwest.

Large numbers even of those who had been farmers in the old country made straight for American cities and towns, living and working there at least until they had saved enough capital to marry and buy farms of their own.

[47] Single young women, most commonly moved straight from field work in rural Sweden to jobs as live-in housemaids in the urban United States.

"Literature and tradition have preserved the often tragic image of the pioneer immigrant wife and mother", writes Barton, "bearing her burden of hardship, deprivation and longing on the untamed frontier ... More characteristic among the newer arrivals, however, was the young, unmarried woman ... As domestic servants in America, they ... were treated as members of the families they worked for and like 'ladies' by American men, who showed them a courtesy and consideration to which they were quite unaccustomed at home.

Many admiring remarks are recorded from the late 19th century about the sophistication and elegance that simple Swedish farm girls would gain in a few years, and about their unmistakably American demeanor.

"[51] A number of well-established and longtime Swedish Americans visited Sweden in the 1870s, making comments that give historians a window on the cultural contrasts involved.

A group from Chicago made the journey in an effort to remigrate and spend their later years in the country of their birth, but changed their minds when faced with the realities of 19th-century Swedish society.

Viewing Swedish class snobbery with indignation, Mattson wrote in his Reminiscences that this contrast was the key to the greatness of the United States, where "labor is respected, while in most other countries it is looked down upon with slight".

He was sardonically amused by the ancient pageantry of monarchy at the ceremonial opening of the Riksdag: "With all respects for old Swedish customs and manners, I cannot but compare this pageant to a great American circus—minus the menagerie, of course.

"[53] Mattson's first recruiting visit came immediately after consecutive seasons of crop failure in 1867 and 1868, and he found himself "besieged by people who wished to accompany me back to America."

The laboring classes, in their turn, appeared to him coarse and degraded, drinking heavily in public, speaking in a stream of curses, making obscene jokes in front of women and children.

This traveller too was incessantly hearing American civilization and culture denigrated from the depths of upper-class Swedish prejudice: "If I, in all modesty, told something about America, it could happen that in reply I was informed that this could not possibly be so or that the matter was better understood in Sweden.

This escalated to a point where its priests even were persecuted by the church for preaching sobriety, and the reactions of many congregation members to that contributed to an inspiration to leave the country (which however was against the law until 1840).

Figures remained high until World War I, alarming both conservative Swedes, who saw emigration as a challenge to national solidarity, and liberals, who feared the disappearance of the labor force necessary for economic development.

One-fourth of all Swedes had made the United States their home,[58] and a broad national consensus mandated that a Parliamentary Emigration Commission study the problem in 1907.

Approaching the task with what Barton calls "characteristic Swedish thoroughness",[59] the Commission published its "Emigration Inquest", including findings and proposals, in 21 large volumes.

The Commission rejected conservative proposals for legal restrictions on emigration and in the end supported the liberal line of "bringing the best sides of America to Sweden" through social and economic reform.

[68] The tetralogy has been filmed by Jan Troell as The Emigrants (1971) and The New Land (1972), and forms the basis of Kristina from Duvemåla, a 1995 musical by former ABBA members Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus.