Sylow theorems

In mathematics, specifically in the field of finite group theory, the Sylow theorems are a collection of theorems named after the Norwegian mathematician Peter Ludwig Sylow[1] that give detailed information about the number of subgroups of fixed order that a given finite group contains.

This is because they give a method for using the prime decomposition of the cardinality of a finite group

to give statements about the structure of its subgroups: essentially, it gives a technique to transport basic number-theoretic information about a group to its group structure.

For example, a typical application of these theorems is in the classification of finite groups of some fixed cardinality, e.g.

[2] Collections of subgroups that are each maximal in one sense or another are common in group theory.

These properties can be exploited to further analyze the structure of G. The following theorems were first proposed and proven by Ludwig Sylow in 1872, and published in Mathematische Annalen.

Corollary — Given a finite group G and a prime number p dividing the order of G, then there exists an element (and thus a cyclic subgroup generated by this element) of order p in G.[3] Theorem (2) — Given a finite group G and a prime number p, all Sylow p-subgroups of G are conjugate to each other.

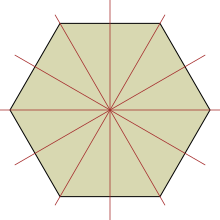

These are the groups generated by a reflection, of which there are n, and they are all conjugate under rotations; geometrically the axes of symmetry pass through a vertex and a side.

By contrast, if n is even, then 4 divides the order of the group, and the subgroups of order 2 are no longer Sylow subgroups, and in fact they fall into two conjugacy classes, geometrically according to whether they pass through two vertices or two faces.

Another example are the Sylow p-subgroups of GL2(Fq), where p and q are primes ≥ 3 and p ≡ 1 (mod q) , which are all abelian.

Most of the examples use Sylow's theorem to prove that a group of a particular order is not simple.

For groups of small order, the congruence condition of Sylow's theorem is often sufficient to force the existence of a normal subgroup.

The only value satisfying these constraints is 1; therefore, there is only one subgroup of order 3, and it must be normal (since it has no distinct conjugates).

Similarly, n5 must divide 3, and n5 must equal 1 (mod 5); thus it must also have a single normal subgroup of order 5.

A more complex example involves the order of the smallest simple group that is not cyclic.

Burnside's pa qb theorem states that if the order of a group is the product of one or two prime powers, then it is solvable, and so the group is not simple, or is of prime order and is cyclic.

A slight generalization known as Burnside's fusion theorem states that if G is a finite group with Sylow p-subgroup P and two subsets A and B normalized by P, then A and B are G-conjugate if and only if they are NG(P)-conjugate.

Burnside's fusion theorem can be used to give a more powerful factorization called a semidirect product: if G is a finite group whose Sylow p-subgroup P is contained in the center of its normalizer, then G has a normal subgroup K of order coprime to P, G = PK and P∩K = {1}, that is, G is p-nilpotent.

Less trivial applications of the Sylow theorems include the focal subgroup theorem, which studies the control a Sylow p-subgroup of the derived subgroup has on the structure of the entire group.

These rely on J. L. Alperin's strengthening of the conjugacy portion of Sylow's theorem to control what sorts of elements are used in the conjugation.

The Sylow theorems have been proved in a number of ways, and the history of the proofs themselves is the subject of many papers, including Waterhouse,[4] Scharlau,[5] Casadio and Zappa,[6] Gow,[7] and to some extent Meo.

[8] One proof of the Sylow theorems exploits the notion of group action in various creative ways.

The group G acts on itself or on the set of its p-subgroups in various ways, and each such action can be exploited to prove one of the Sylow theorems.

This is an instance of Kummer's theorem (since in base p notation the number |G| ends with precisely k + r digits zero, subtracting pk from it involves a carry in r places), and can also be shown by a simple computation: and no power of p remains in any of the factors inside the product on the right.

It may be noted that conversely every subgroup H of order pk gives rise to sets ω ∈ Ω for which Gω = H, namely any one of the m distinct cosets Hg.

Lemma — Let H be a finite p-group, let Ω be a finite set acted on by H, and let Ω0 denote the set of points of Ω that are fixed under the action of H. Then |Ω| ≡ |Ω0| (mod p).

Any element x ∈ Ω not fixed by H will lie in an orbit of order |H|/|Hx| (where Hx denotes the stabilizer), which is a multiple of p by assumption.

Now let P act on Ω by conjugation, and again let Ω0 denote the set of fixed points of this action.

In permutation groups, it has been proven, in Kantor[12][13][14] and Kantor and Taylor,[15] that a Sylow p-subgroup and its normalizer can be found in polynomial time of the input (the degree of the group times the number of generators).

These algorithms are described in textbook form in Seress,[16] and are now becoming practical as the constructive recognition of finite simple groups becomes a reality.