Sylvanus Morley

[6] His first field trip to Mexico and Yucatán was in January of the same year, when he visited and explored several Maya sites, including Acanceh, Labna, Kabah, Uxmal, Zayil, and Kiuic.

[17] Morley produced extensive analyses (he filed over 10,000 pages of reports)[18] on many issues and observations of the region, including detailed coastline charting and identification of political and social attitudes which could be viewed as "threatening" to U.S. interests.

[23] Morley was to devote most of the next two decades to fieldwork in the Maya region, overseeing the seasonal archaeological digs and restoration projects, returning to the United States in the off-season to give a series of lectures on his finds.

Although primarily involved with the work at Chichen Itza, Morley also took on responsibilities which extended Carnegie-sponsored fieldwork to other Maya sites, such as Yaxchilan, Coba, Copán, Quiriguá, Uxmal, Naranjo, Seibal and Uaxactun.

Because of cost and schedule overruns as well as criticisms of the quality of some of the research produced, the Carnegie board began to believe that managing multiple projects was not Morley's forte.

[25] Slightly built and not noted for possessing a strong constitution, Morley saw his health deteriorate over the years spent laboring in the Central American jungles under often adverse conditions.

Chichen Itza had evidently been functionally abandoned long before the Spanish first came, although the local indigenous Yucatec Maya still lived in settlements nearby, and even within its former boundaries (but in recently built wooden huts, not the stone buildings themselves).

[26] When Morley and his team returned in 1924 to commence their excavations, Chichen Itza was a sprawling complex of several large ruined buildings and many smaller ones, most of which lay concealed under mounds of earth and vegetation.

In particular, this complex and some others which were gradually revealed appeared to have much in common with structures built at Tula, believed to be the capital of the Toltecs and which was located about 100 km north of present-day Mexico City.

A separate archaeological dig, this one under the Mexican government, had also commenced working the site; the two projects divided the areas to excavate, continuing side-by-side for several years, in a somewhat guarded but nonetheless cordial fashion.

While I agree with his results on the inscriptions of the Old Empire cities which contain many dates and time periods, I find that his method of dealing solely with calendrical matter fails at Chichen Itza, since there are but few hieroglyphs of that nature.

[30] The chronology of Chichen Itza continues to be a source of debate, and the hoped-for answers to the mystery of the Classic Maya decline elusive (wholesale "Mexicanisation" by invading forces ruled out by the lack of these indicators in the central and southern sites).

The Ancient Maya was to be one of his more successful works (outside of his popular writings in magazines), and has been posthumously revised and reprinted several times, although since the 1980s Morley's name is no longer listed as the main author.

Proskouriakoff also went on to establish a stellar career and a lifelong association with the Carnegie Institution; however, her researches ultimately provided the primary convincing evidence which later disproved much of what had been maintained by Thompson and Morley.

In 1925, a young English Cambridge anthropology student named John Eric Sidney Thompson wrote to Morley seeking employment with the Carnegie programme on digs in Central America.

Towards the end of the Chichen Itza project, Morley came across the drawings of a young artist and draftsperson, Tatiana Proskouriakoff, who as an unpaid excavator had accompanied a 1936–37 University of Pennsylvania Museum expedition to the Maya site of Piedras Negras.

Morley maintained that ancient Maya society was essentially a united theocracy, and one which was almost exclusively devoted to astronomical observations and mystically noting (even "worshipping") the passage of time.

These ideas (which Thompson's later work would develop to its fullest extent) are now extensively modified, and although astronomical and calendric observations were clearly important to the Maya, the people themselves are now seen in more historical, realistic terms—concerned also with dynastic succession, political conquests, and the lives and achievements of actual personages.

[37] It is now generally accepted that at no time was the Maya region united under a single polity, but rather that individual "city-states" maintained a somewhat independent existence, albeit one with its fluctuating conquests and local subservience to more dominant centers.

"[40] That is to say, in Morley's view each glyph substantially represented words, ideas and concepts in toto, and did not separately depict the individual language sounds as spoken by the scribes who had written them (with the possible exception of an occasional rebus-like element, as had already been demonstrated for Aztec writing).

Over the next decades other Mayanists such as Proskouriakoff, Michael D. Coe, and David H. Kelley would further expand upon this phonetic line of enquiry, which ran counter to the accepted view but would prove to be ever more fruitful as their work continued.

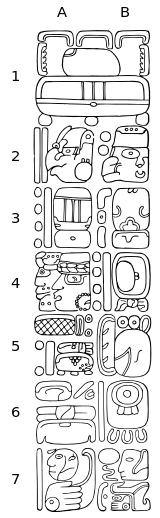

He was particularly proficient at recovering calendar dates from well-worn and weathered inscriptions, owing to his great familiarity with the various glyphic styles of the tzolk'in, haab' and Long Count elements.

Some leading figures from a later generation of Mayanists would come to regard his publications as being inferior in detail and scope to that of his predecessors, such as Teoberto Maler and Alfred Maudslay — poorer quality reproductions, omitted texts, sometimes inaccurate drawings.

The reconstructions of Chichen Itza and other sites were widely admired; but in terms of the research output and the resulting documentation produced, the legacy of these projects did not quite amount to what might have been expected to come from such a lengthy investigation.

Perhaps the contributions that today remain the most relevant arise from his instigation of the Carnegie research programmes, his enthusiasm and support shown to other scholars, and the undeniable successes in the restorative efforts that have made the Maya sites justly famous.

He had particular talents in communicating his fascination for the subject to a wider audience, and in his lifetime became quite widely known as perhaps the quintessential model of an early 20th-century Central American scholar and explorer, complete with his ever-present pith helmet.

Some have even speculated[47] that his life and exploits may have provided some of the inspiration for the character of Indiana Jones in the Spielberg films; the Carnegie Institute itself mentions that it might also have been Morley's field director at Chichen Itza, Earl Morris.

[48] Sylvanus Morley was also to be remembered as a spokesman and representative of the Maya peoples, among whom he spent so much of his time, and who otherwise lacked the means to directly address some of their concerns with the wider public.

Several later archaeologists would recall that their youthful exposure to these articles, "vividly illustrated with a color rendition of a purported virgin in filmy huipil [a type of clothing] being hurled into the Sacred Cenote", had drawn them into the field in the first place.

[53] In his autobiography, the Spanish professor noted the effect of this name change and subsequent confusion: However, the person with the most right to complain was my cousin Sylvanus Griswold Morley, the celebrated archaeologist.