Symmetric group

factorial) such permutation operations, the order (number of elements) of the symmetric group

[1] For finite sets, "permutations" and "bijective functions" refer to the same operation, namely rearrangement.

which are not solvable by radicals, that is, the solutions cannot be expressed by performing a finite number of operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and root extraction on the polynomial's coefficients.

In the representation theory of Lie groups, the representation theory of the symmetric group plays a fundamental role through the ideas of Schur functors.

In combinatorics, the symmetric groups, their elements (permutations), and their representations provide a rich source of problems involving Young tableaux, plactic monoids, and the Bruhat order.

The kernel of this homomorphism, that is, the set of all even permutations, is called the alternating group An.

The group Sn is the semidirect product of An and any subgroup generated by a single transposition.

We denote such a cycle by (1 4 3), but it could equally well be written (4 3 1) or (3 1 4) by starting at a different point.

Every element of Sn can be written as a product of disjoint cycles; this representation is unique up to the order of the factors, and the freedom present in representing each individual cycle by choosing its starting point.

The order reversing permutation is the one given by: This is the unique maximal element with respect to the Bruhat order and the longest element in the symmetric group with respect to generating set consisting of the adjacent transpositions (i i+1), 1 ≤ i ≤ n − 1.

(non-adjacent) transpositions so it thus has sign: which is 4-periodic in n. In S2n, the perfect shuffle is the permutation that splits the set into 2 piles and interleaves them.

The low-degree symmetric groups have simpler and exceptional structure, and often must be treated separately.

generates Sn subject to the following relations:[7] where 1 represents the identity permutation.

The symmetric group on an infinite set does not have a subgroup of index 2, as Vitali (1915[12]) proved that each permutation can be written as a product of three squares.

However it contains the normal subgroup S of permutations that fix all but finitely many elements, which is generated by transpositions.

That result, often called the Schreier-Ulam theorem, is superseded by a stronger one which says that the nontrivial normal subgroups of the symmetric group on a set

The maximal subgroups of Sn fall into three classes: the intransitive, the imprimitive, and the primitive.

The primitive maximal subgroups are more difficult to identify, but with the assistance of the O'Nan–Scott theorem and the classification of finite simple groups, (Liebeck, Praeger & Saxl 1988) gave a fairly satisfactory description of the maximal subgroups of this type, according to (Dixon & Mortimer 1996, p. 268).

The Sylow subgroups of the symmetric groups are important examples of p-groups.

They are more easily described in special cases first: The Sylow p-subgroups of the symmetric group of degree p are just the cyclic subgroups generated by p-cycles.

Note however that (Kerber 1971, p. 26) attributes the result to an 1844 work of Cauchy, and mentions that it is even covered in textbook form in (Netto 1882, §39–40).

For example, in S5, one cyclic subgroup of order 5 is generated by (13254), whereas the largest cyclic subgroups of S5 are generated by elements like (123)(45) that have one cycle of length 3 and another cycle of length 2.

In fact, for any set X of cardinality other than 6, every automorphism of the symmetric group on X is inner, a result first due to (Schreier & Ulam 1936) according to (Dixon & Mortimer 1996, p. 259).

This homology is easily computed as follows: Sn is generated by involutions (2-cycles, which have order 2), so the only non-trivial maps Sn → Cp are to S2 and all involutions are conjugate, hence map to the same element in the abelianization (since conjugation is trivial in abelian groups).

One must also show that the sign map is well-defined, but assuming that, this gives the first homology of Sn.

The homology "stabilizes" in the sense of stable homotopy theory: there is an inclusion map Sn → Sn+1, and for fixed k, the induced map on homology Hk(Sn) → Hk(Sn+1) is an isomorphism for sufficiently high n. This is analogous to the homology of families Lie groups stabilizing.

This has a large area of potential applications, from symmetric function theory to problems of quantum mechanics for a number of identical particles.

Its conjugacy classes are labeled by partitions of n. Therefore, according to the representation theory of a finite group, the number of inequivalent irreducible representations, over the complex numbers, is equal to the number of partitions of n. Unlike the general situation for finite groups, there is in fact a natural way to parametrize irreducible representation by the same set that parametrizes conjugacy classes, namely by partitions of n or equivalently Young diagrams of size n. Each such irreducible representation can be realized over the integers (every permutation acting by a matrix with integer coefficients); it can be explicitly constructed by computing the Young symmetrizers acting on a space generated by the Young tableaux of shape given by the Young diagram.

If the field K has characteristic equal to zero or greater than n then by Maschke's theorem the group algebra KSn is semisimple.

The determination of the irreducible modules for the symmetric group over an arbitrary field is widely regarded as one of the most important open problems in representation theory.

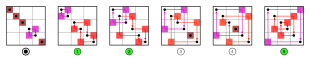

These are the positions of the six matrices

Some matrices are not arranged symmetrically to the main diagonal – thus the symmetric group is not abelian.