London Philharmonic Orchestra

In addition to its work at the Festival Hall and Glyndebourne, the LPO performs regularly at the Congress Theatre, Eastbourne and the Brighton Dome, and tours nationally and internationally.

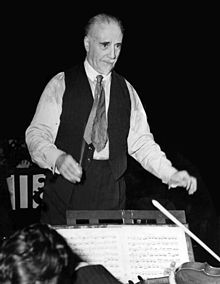

Beecham demanded more personal control of the orchestra and repertoire than the BBC was willing to concede, and his priorities were the opera house and the concert hall rather than the broadcasting studio.

[8] Originally Sargent and Beecham envisaged a reshuffled version of the LSO, but the orchestra, a self-governing body, balked at weeding out and replacing underperforming players.

"[12] In a study of the foundation of the LPO, David Patmore writes, "The combination of steady work, occasionally higher than usual rates, variety of performance and Beecham's own magnetic personality would make such an offering irresistible to many orchestral musicians.

"[5] Beecham and Sargent had financial backing from leading figures in commerce, including Samuel Courtauld, Robert Mayer and Baron Frédéric d'Erlanger,[13] and secured profitable contracts to record for Columbia and play for the Royal Philharmonic Society, the Royal Choral Society, the Courtauld-Sargent Concerts, Mayer's concerts for children, and the international opera season at Covent Garden.

[16] During the early years, the orchestra was led by Paul Beard and David McCallum, and included leading players such as James Bradshaw, Gwydion Brooke, Geoffrey Gilbert, Léon Goossens, Gerald Jackson, Reginald Kell, Anthony Pini and Bernard Walton.

[25] During the next eight years, the LPO appeared nearly a hundred times at the Queen's Hall for the Royal Philharmonic Society, played for Beecham's opera seasons at Covent Garden, and made more than 300 gramophone records.

[29] In the Courtauld-Sargent series the LPO played not only under Sargent but under many guests including Bruno Walter, George Szell, Fritz Busch and Igor Stravinsky.

[34] As his sixtieth birthday approached in 1939, Beecham was advised by his doctors to take a year's break from conducting, and he planned to go abroad to rest in a warm climate, leaving the orchestra in other hands.

[36] The original LPO company was liquidated and Beecham raised large sums of money for the orchestra, helping its members to form themselves into a self-governing body.

[37] During the war, the LPO played in the capital and on continual tours of Britain, under Sargent and other conductors, including 50 under Richard Tauber, bringing orchestral concerts to places where they had rarely if ever been given.

[46] With Boult the LPO began a series of commercial recordings, beginning with Elgar's Falstaff, Mahler's Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen with the mezzo-soprano Blanche Thebom, and Beethoven's First Symphony.

The other works were Elgar's Introduction and Allegro, Holst's The Perfect Fool ballet music, Richard Strauss's Don Juan, and Stravinsky's Firebird.

Kennedy speculates that Boult's change of mind was due to a growing conviction that the orchestra would be "seriously jeopardized financially" if Russell remained in post.

[53] A later writer, Richard Witts, suggests that Boult sacrificed Russell because he believed doing so would enhance the LPO's chance of being appointed resident orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall.

[55] In 1956 the LPO toured the Soviet Union, the first British orchestra to do so; the conductors were Boult, Anatole Fistoulari and George Hurst, and the soloists were Alfredo Campoli and Moura Lympany.

This was a bad period financially for the orchestra, and it was forced to abandon fixed contracts for its players with holiday and sick pay and pensions, and revert to payment by engagement.

[64] During the 1960s the orchestra gave fund-raising concerts in which guests from outside the world of classical music appeared, including Danny Kaye, Duke Ellington and Tony Bennett.

His concerts made a strong impression with the public, and within months the LPO was playing to ninety per cent capacity audiences at the Festival Hall, far outstripping the other London orchestras.

[70] In 1973, the LPO was caught up in a recurring phenomenon of London orchestral life: the conviction in official circles that having four independent orchestras is too much for one city, and that two or more of the existing ensembles should merge.

In 1973, acting jointly with the LSO, the LPO acquired and began restoring a disused church in Southwark, converting it into the Henry Wood Hall, a convenient and acoustically excellent rehearsal space and recording studio, opened in 1975.

Unlike his two predecessors Tennstedt preferred to record with the LPO rather than major continental or American orchestras; among the many sets they made together was a complete cycle of Mahler's symphonies for EMI.

In 1985 this tradition was broken with the recruitment of John Willan, a qualified accountant as well as an alumnus of the Royal Academy of Music and a successful recording producer for EMI.

[83] He brought with him a recording contract with EMI, but management turnover, financial stresses, and political disputes at the Southbank Centre at the time contributed to the difficulty of the working atmosphere in the orchestra.

This proved a mixed blessing: the Southbank Centre management now had a say over concert programming, and insisted on the inclusion of works by obscure composers[n 7] which did severe damage to box-office receipts.

[86] In 1993 another official attempt to create a "super-orchestra" at the expense of one or more of the existing London ensembles briefly damaged relations between the LPO and the Philharmonia, but the idea was quickly abandoned, and in 1995, with the consent of the Arts Council, the two orchestras agreed to share the residency at the Festival Hall.

The orchestra's first gramophone set was made before its debut concert; with Sargent and the Royal Choral Society the LPO recorded choruses from Messiah and The Creation at Kingsway Hall in September 1932.

[106] Other conductors who worked in the EMI studios with the orchestra in its early years included Elgar, Felix Weingartner, John Barbirolli, and Serge Koussevitzky.

[108] Among those who recorded with the orchestra for Decca were van Beinum, Sargent, de Sabata, Furtwängler, Charles Munch, Clemens Krauss, Hans Knappertsbusch, Erich Kleiber and the young Solti.

Later scores have included those for Antony and Cleopatra (1972), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), Disney's Tron (1982), The Fly (1986), Dead Ringers (1988), In the Name of the Father (1993), the Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001–03) and most of the music for the three films derived from The Hobbit (2012–14).

(modern reconstruction of unavailable original)