Symphony No. 6 (Tchaikovsky)

The Russian title of the symphony, Патетическая (Pateticheskaya), means "passionate" or "emotional", not "arousing pity," but it is a word reflective of a touch of concurrent suffering.

Its French translation Pathétique is generally used in French, Spanish, English, German and other languages,[5] Many English-speaking classical musicians had, by the early 20th century, adopted an English spelling and pronunciation for Tchaikovsky's symphony, dubbing it "The Pathetic", as shorthand to differentiate it from a popular 1798 Beethoven piano sonata also known as The Pathétique.

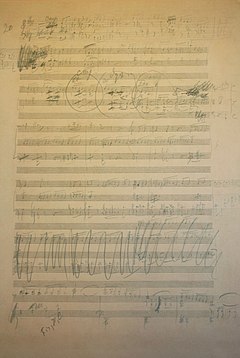

[8] However, some or all of the symphony was not pleasing to Tchaikovsky, who tore up the manuscript "in one of his frequent moods of depression and doubt over his alleged inability to create".

[8] In 1892, Tchaikovsky wrote the following to his nephew Vladimir "Bob" Davydov: The symphony is only a work written by dint of sheer will on the part of the composer; it contains nothing that is interesting or sympathetic.

[11] However, the composer began to feel apprehension over his symphony, when, at rehearsals, the orchestra players did not exhibit any great admiration for the new work.

The introduction is formed from repeated modules of its initial theme, presented by the bassoon, whose purpose seems to be to open a dominant chord, failing to do so.

This section introduces the motif of the full, octave-long downward scale, which recurs throughout the symphony; it eventually leads to a long medial caesura that gives way to the secondary theme in D major.

The energetic development section begins abruptly with an outburst from the full orchestra, with half-diminished harmony that leads uneasily to D minor.

Tchaikovsky soon goes into something more nightmarish, which culminates in an explosion of despair and misery in B minor, accompanied by a strong and repetitive four-note figure in the brass, which recalls the motif from the introduction.

This leads to the jubilant E major secondary theme in full, first given quietly by unison clarinets with a continued string accompaniment.

It is probably no coincidence that the movement, with its stormy character through restless strings, wind-like whistling woodwinds and thundering brass instruments, is reminiscent of the finale from Joachim Raff's Symphony No.

[20] Back in B minor, although opened with striking half-diminished harmony, the fourth movement takes a slow six-part sonata rondo form (A-B-A-C-A-B).

The music fades into a single, unique strike of a tam-tam; this quietly introduces a funereal chorale in the low brass which rounds off the dominant harmony.

Had Tchaikovsky followed the standard four-movement structure, the movements would have been ordered like this: Tchaikovsky critic Richard Taruskin writes: Suicide theories were much stimulated by the Sixth Symphony, which was first performed under the composer's baton only nine days before his demise, with its lugubrious finale (ending morendo, 'dying away'), its brief but conspicuous allusion to the Orthodox requiem liturgy in the first movement and above all its easily misread subtitle.

[22]In the words of the critic Alexander Poznansky, "Since the arrival of the 'court of honour' theory in the West, performances of Tchaikovsky's last symphony are almost invariably accompanied by annotations treating it as a testimony of homosexual martyrdom.

"[23] Yet critic David Brown describes the idea of the Sixth Symphony as some sort of suicide note as "patent nonsense".

[24] Other scholars, including Michael Paul Smith, believe that with or without the supposed 'court of honour' sentence, there is no way that Tchaikovsky could have known the time of his own death while composing his last masterpiece.

There is also evidence that Tchaikovsky was unlikely to have been depressed while composing the symphony, with his brother noting of him after he had sent the manuscript for publishing, "I had not seen him so bright for a long time past.

As always, they found what they were looking for: a brief but conspicuous quotation from the Russian Orthodox requiem at the stormy climax of the first movement, and of course the unconventional Adagio finale with its tense harmonies at the onset and its touching depiction of the dying of the light in conclusion".

"[32] Simon Karlinsky, a composer[33] and professor of Slavic languages and literature at UC Berkeley and "an expert on homosexuality in pre-Soviet culture",[34] wrote in the gay literary magazine Christopher Street in 1988 that in 1941 a musician friend of his youth called Alex, who had spent several months associating with the painter Pavel Tchelitchew, told him an oral tradition that Tchelitchew had heard from the composer's brother Modest, told to him by Tchaikovsky himself.

That theme also served as the melody of "Where" by Tony Williams and The Platters (a 1959 hit for them), "In Time" by Steve Lawrence (1961) and "John O'Dreams" by Bill Caddick (1976); however, all four songs have different lyrics.

[citation needed] Excerpts from the symphony can be heard in a number of films, including Victor Young's theme for Howard Hughes' 1943 American western The Outlaw, 1942's Now, Voyager, the 1997 version of Anna Karenina, as well as The Ruling Class, Minority Report, Sweet Bird of Youth, Soylent Green, Maurice, The Aviator, and The Death of Stalin.

[citation needed] The symphony plays a major role in E. M. Forster's novel Maurice (written in 1913 and later, but unpublished until 1971), where it serves as a veiled reference to homosexuality.