Syncom

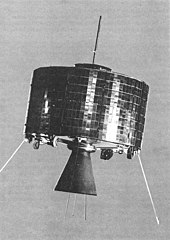

The three early Syncom satellites were experimental spacecraft built by Hughes Aircraft Company's facility in Culver City, California, by a team led by Harold Rosen, Don Williams, and Thomas Hudspeth.

During the first year of Syncom 2 operations, NASA conducted voice, teletype, and facsimile tests,[4] as well as 110 public demonstrations to show the capabilities of this satellite and invite feedback.

[5][circular reference][6] Syncom 2 also relayed a number of test television transmissions from Fort Dix, New Jersey to a ground station in Andover, Maine, beginning on September 29, 1963.

The satellite, in orbit near the International Date Line, had the addition of a wideband channel for television and was used to telecast the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo to the United States.

On January 1, 1965, NASA transferred operation of the satellites to the United States Department of Defense (DOD) along with telemetry, command stations, and range and rangefinding equipment.

At 4.26 metres (14.0 ft), the satellites were the first to be designed for launch from the Space Shuttle payload bay,[13] and were deployed like a Frisbee.

They were made with a solid rocket motor for initial perigee burn and hydrazine propellant for station keeping and spin stabilization.

"[15] Hughes was contracted to provide a worldwide communications system based on four satellites, one over the continental United States (CONUS), and one each over the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans, spaced about 90 degrees apart.

This was followed on April 12, 1985 by Leasat F3 on STS-51-D. F3's launch was declared a failure when the satellite failed to start its maneuver to geostationary orbit once released from Discovery.

[17] Hughes had an insurance policy on the satellite, and so claimed a total loss for the spacecraft of about $200 million, an amount underwritten by numerous parties.

However, with another satellite planned to be launched, it was determined that a space walk by a subsequent Shuttle crew might be able to "wake" the craft.

A "bypass box" was hastily constructed, NASA was excited to offer assistance, the customer was supportive, and the insurance underwriters agreed to fund the first ever attempt at space salvage.

[16] Remembering this second failure of F4, and with F1 beginning to wear out at the spin bearing, it was decided to "flip" F1 every six months to keep the payload in the sun.

Leasat F4 was subsequently powered down and moved to a graveyard orbit with a large amount of station keeping fuel in reserve.

This was fortuitous; when another satellite suffered a loss of its fuel ten years later, Hughes engineers pioneered the use of alternative propellants with Leasat F4.