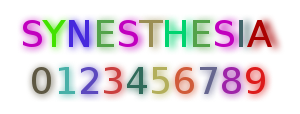

Synesthesia

The earliest recorded case of synesthesia is attributed to the Oxford University academic and philosopher John Locke, who, in 1690, made a report about a blind man who said he experienced the color scarlet when he heard the sound of a trumpet.

People with synesthesia related to music may also have perfect pitch because their ability to see and hear colors aids them in identifying notes or keys.

[20] Some authors have argued that the term synaesthesia may not be correct when applied to the so-called grapheme-colour synesthesia and similar phenomena in which the inducer is conceptual (e.g. a letter or number) rather than sensory (e.g. sound or color).

[23] In August 2017 a research article in the journal Social Neuroscience reviewed studies with fMRI to determine if persons who experience autonomous sensory meridian response are experiencing a form of synesthesia.

While a determination has not yet been made, there is anecdotal evidence that this may be the case, based on significant and consistent differences from the control group, in terms of functional connectivity within neural pathways.

Synesthetes have used their abilities in memorization of names and telephone numbers, mental arithmetic, and more complex creative activities like producing visual art, music, and theater.

[46] It has been suggested that individual development of perceptual and cognitive skills, in addition to one's cultural environment, produces the variety in awareness and practical use of synesthetic phenomena.

In one study, conducted by Julia Simner of the University of Edinburgh, it was found that spatial sequence synesthetes have a built-in and automatic mnemonic reference.

Whereas a non-synesthete will need to create a mnemonic device to remember a sequence (like dates in a diary), a synesthete can simply reference their spatial visualizations.

Cytowic and Eagleman find support for the disinhibition idea in the so-called acquired forms[3] of synesthesia that occur in non-synesthetes under certain conditions: temporal lobe epilepsy,[51] head trauma, stroke, and brain tumors.

They also note that it can likewise occur during stages of meditation, deep concentration, sensory deprivation, or with the use of psychedelics such as LSD or mescaline, and even, in some cases, marijuana.

[52] Due to the prevalence of synesthesia among the first-degree relatives of people affected,[53] there may be a genetic basis, as indicated by the monozygotic twins studies showing an epigenetic component.

[medical citation needed] Synesthesia might also be an oligogenic condition, with locus heterogeneity, multiple forms of inheritance, and continuous variation in gene expression.

[54] Women have a higher chance of developing synesthesia, as demonstrated in population studies conducted in the city of Cambridge, England where females were 6 times more likely to have it.

However, the criteria are different in the second book:[1][2][3] Cytowic's early cases mainly included individuals whose synesthesia was frankly projected outside the body (e.g., on a "screen" in front of one's face).

Additionally, one kind of musical scale (genos) introduced by Plato's friend Archytas of Tarentum in the fourth century BC was named chromatic.

In Plato's time, the description of melody as 'colored' had become part of professional jargon, while the musical terms 'tone' and 'harmony' soon became integrated into the vocabulary of color in visual art.

[70] In the early 1920s, the Bauhaus teacher and musician Gertrud Grunow researched the relationships between sound, color, and movement and developed a 'twelve-tone circle of colour' which was analogous with the twelve-tone music of the Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951).

[citation needed] As the 1980s cognitive revolution made inquiry into internal subjective states respectable again, scientists returned to studying synesthesia.

Led in the United States by Larry Marks and Richard Cytowic, and later in England by Simon Baron-Cohen and Jeffrey Gray, researchers explored the reality, consistency, and frequency of synesthetic experiences.

Psychologists and neuroscientists study synesthesia not only for its inherent appeal but also for the insights it may give into cognitive and perceptual processes that occur in synesthetes and non-synesthetes alike.

[citation needed] Solomon Shereshevsky, a newspaper reporter turned mnemonist, was discovered by Russian neuropsychologist Alexander Luria to have a rare fivefold form of synesthesia,[17] of which he is the only known case.

[17] Shereshevsky could recount endless details of many things without form, from lists of names to decades-old conversations, but he had great difficulty grasping abstract concepts.

Linda Anderson, according to NPR considered "one of the foremost living memory painters", creates with oil crayons on fine-grain sandpaper representations of the auditory-visual synaesthesia she experiences during severe migraine attacks.

[85][86] Brandy Gale, a Canadian visual artist, experiences an involuntary joining or crossing of any of her senses – hearing, vision, taste, touch, smell and movement.

Gale paints from life rather than from photographs and by exploring the sensory panorama of each locale attempts to capture, select, and transmit these personal experiences.

[87][88][89] David Hockney perceives music as color, shape, and configuration and uses these perceptions when painting opera stage sets (though not while creating his other artworks).

Alexander Scriabin composed colored music that was deliberately contrived and based on the circle of fifths, whereas Olivier Messiaen invented a new method of composition (the modes of limited transposition) specifically to render his bi-directional sound–color synesthesia.

"[94] British composer Daniel Liam Glyn created the classical-contemporary music project Changing Stations using Grapheme Colour Synaesthesia.

[citation needed] Research on synesthesia raises questions about how the brain combines information from different sensory modalities, referred to as crossmodal perception or multisensory integration.