Syriac language

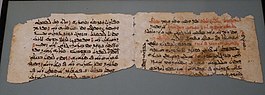

[11] It emerged during the first century AD from a local Eastern Aramaic dialect that was spoken in the ancient region of Osroene, centered in the city of Edessa.

Primarily a Christian medium of expression, Syriac had a fundamental cultural and literary influence on the development of Arabic,[21] which largely replaced it during the later medieval period.

[28] In English scholarly literature, the term "Syriac" is preferred over the alternative form "Syrian", since the latter is much more polysemic and commonly relates to Syria in general.

[32][34][35][13][33][36] Practice of interchangeable naming (Aramaya, Urhaya, Nahraya, and Suryaya) persisted for centuries, in common use and also in works of various prominent writers.

Preference of early scholars towards the use of the Syrian/Syriac label was also relied upon its notable use as an alternative designation for Aramaic language in the "Cave of Treasures",[42] long held to be the 4th century work of an authoritative writer and revered Christian saint Ephrem of Edessa (d. 373), who was thus believed to be proponent of various linguistic notions and tendencies expressed in the mentioned work.

[49][50] Native (endonymic) use of the term Aramaic language (Aramaya/Oromoyo) among its speakers has continued throughout the medieval period, as attested by the works of prominent writers, including the Oriental Orthodox Patriarch Michael of Antioch (d.

[51] Since the proper dating of the Cave of Treasures,[52] modern scholars were left with no indications of native Aramaic adoption of Syrian/Syriac labels before the 5th century.

In the same time, a growing body of later sources showed that both in Greek, and in native literature, those labels were most commonly used as designations for Aramaic language in general, including its various dialects (both eastern and western),[53] thus challenging the conventional scholarly reduction of the term "Syriac language" to a specific designation for Edessan Aramaic.

Those problems were addressed by prominent scholars, including Theodor Nöldeke (d. 1930) who noted on several occasions that term "Syriac language" has come to have two distinctive meanings, wider and narrower, with first (historical and wider) serving as a common synonym for Aramaic language in general, while other (conventional and narrower) designating only the Edessan Aramaic, also referred to more specifically as the "Classical Syriac".

[58][59][41][60][61] Inconsistent use of "Syrian/Syriac" labels in scholarly literature has led some researchers to raise additional questions, related not only to terminological issues but also to some more fundamental (methodological) problems, that were undermining the integrity of the field.

[62] Attempts to resolve those issues were unsuccessful, and in many scholarly works, related to the old literary and liturgical language, reduction of the term "Classical Syriac" to "Syriac" (only) remained a manner of convenience, even in titles of works, including encyclopedic entries, thus creating a large body of unspecific references, that became a base for the emergence of several new classes of terminological problems at the advent of the informational era.

[74] Since the occurrence of major political changes in the Near East (2003), those issues have acquired additional complexity, related to legal recognition of the language and its name.

Legal and other practical (educational and informational) aspects of the linguistic self-identification also arose throughout Syriac-speaking diaspora, particularly in European countries (Germany, Sweden, Netherlands).

It has been found as far afield as Hadrian's Wall in Great Britain, with inscriptions written by Aramaic-speaking soldiers of the Roman Empire.

[80][81] During the first three centuries of the Common Era, a local Aramaic dialect spoken in the Kingdom of Osroene, centered in Edessa, eastern of Euphrates, started to gain prominence and regional significance.

Since Old-Edessan Aramaic later developed into Classical Syriac, it was retroactively labeled by western scholars as "Old Syrian/Syriac" or "Proto-Syrian/Syriac", although the linguistic homeland of the language in the region of Osroene, was never part of contemporary (Roman) Syria.

Early literary efforts were focused on creation of an authoritative Aramaic translation of the Bible, the Peshitta (ܦܫܝܛܬܐ Pšīṭtā).

[93] At the same time, Ephrem the Syrian was producing the most treasured collection of poetry and theology in the Edessan Aramaic language, that later became known as Syriac.

[citation needed] The Christological differences with the Church of the East led to the bitter Nestorian Schism in the Syriac-speaking world.

Although remaining a single language with a high level of comprehension between the varieties, the two employ distinctive variations in pronunciation and writing system, and, to a lesser degree, in vocabulary.

[21] Having an Aramaic (Syriac) substratum, the regional Arabic dialect (Mesopotamian Arabic) developed under the strong influence of local Aramaic (Syriac) dialects, sharing significant similarities in language structure, as well as having evident and stark influences from previous (ancient) languages of the region.

From the 7th century onwards, Syriac gradually gave way to Arabic as the spoken language of much of the region, excepting northern Iraq and Mount Lebanon.

The Mongol invasions and conquests of the 13th century, and the religiously motivated massacres of Syriac Christians by Timur further contributed to the rapid decline of the language.

[clarification needed] Modern forms of literary Syriac have also been used not only in religious literature but also in secular genres, often with Assyrian nationalistic themes.

[98] It is also taught in some public schools in Iraq, Syria, Palestine,[99] Israel, Sweden,[100][101] Augsburg (Germany) and Kerala (India).

In 2014, an Assyrian nursery school could finally be opened in Yeşilköy, Istanbul[102] after waging a lawsuit against the Ministry of National Education which had denied it permission, but was required to respect non-Muslim minority rights as specified in the Treaty of Lausanne.

[103] In August 2016, the Ourhi Centre was founded by the Assyrian community in the city of Qamishli, to educate teachers in order to make Syriac an additional language to be taught in public schools in the Jazira Region of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria,[104] which then started with the 2016/17 academic year.

The first stem is the ground state, or Pəʿal (this name models the shape of the root) form of the verb, which carries the usual meaning of the word.

The basic G-stem or "Peal" conjugation of "to write" in the perfect and imperfect is as follows:[107] Phonologically, like the other Northwest Semitic languages, Syriac has 22 consonants.

The various Modern Eastern Aramaic vernaculars have quite different pronunciations, and these sometimes influence how the classical language is pronounced, for example, in public prayer.

ܛܘܼܒܲܝܗܘܿܢ ܠܐܲܝܠܹܝܢ ܕܲܕ݂ܟܹܝܢ ܒܠܸܒ̇ܗܘܿܢ܄ ܕܗܸܢ݂ܘܿܢ ܢܸܚܙܘܿܢ ܠܐܲܠܵܗܵܐ܂

Ṭūḇayhōn l-ʾaylên da-ḏḵên b-lebbhōn, d-hennōn neḥzōn l-ʾălāhā .

'Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.'