Syriac alphabet

In addition to the sounds of the language, the letters of the Syriac alphabet can be used to represent numbers in a system similar to Hebrew and Greek numerals.

The Serṭā variant specifically has been adapted to write Western Neo-Aramaic, previously written in the square Maalouli script, developed by George Rizkalla (Rezkallah), based on the Hebrew alphabet.

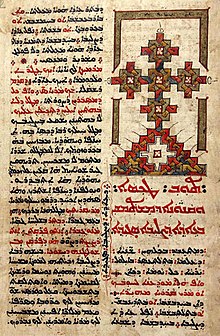

Vowel marks are usually not used with ʾEsṭrangēlā, being the oldest form of the script and arising before the development of specialized diacritics.

Other names for the script include Swāḏāyā (ܣܘܵܕ݂ܵܝܵܐ, 'conversational' or 'vernacular', often translated as 'contemporary', reflecting its use in writing modern Neo-Aramaic), ʾĀṯōrāyā (ܐܵܬ݂ܘܿܪܵܝܵܐ, 'Assyrian', not to be confused with the traditional name for the Hebrew alphabet), Kaldāyā (ܟܲܠܕܵܝܵܐ, 'Chaldean'), and, inaccurately, "Nestorian" (a term that was originally used to refer to the Church of the East in the Sasanian Empire).

The Eastern script uses a system of dots above and/or below letters, based on an older system, to indicate vowel sounds not found in the script: It is thought that the Eastern method for representing vowels influenced the development of the niqqud markings used for writing Hebrew.

Whether because its distribution is mostly predictable (usually inside a syllable-initial two-consonant cluster) or because its pronunciation was lost, both the East and the West variants of the alphabet traditionally have no sign to represent the schwa.

The West Syriac dialect is usually written in the Serṭā or Serṭo (ܣܶܪܛܳܐ, 'line') form of the alphabet, also known as the Pšīṭā (ܦܫܺܝܛܳܐ, 'simple'), 'Maronite' or the 'Jacobite' script (although the term Jacobite is considered derogatory).

A cursive chancery hand is evidenced in the earliest Syriac manuscripts, but important works were written in ʾEsṭrangēlā.

[8] These dots, having no sound value in themselves, arose before both eastern and western vowel systems as it became necessary to mark plural forms of words, which are indistinguishable from their singular counterparts in regularly-inflected nouns.

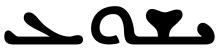

Besides plural nouns, syāmē are also placed on: Syriac uses a line, called mṭalqānā (ܡܛܠܩܢܐ, literally 'concealer', also known by the Latin term linea occultans in some grammars), to indicate a silent letter that can occur at the beginning or middle of a word.

[9] In Eastern Syriac, this line is diagonal and only occurs above the silent letter (e.g. ܡܕ݂ܝܼܢ݇ܬܵܐ, 'city', pronounced mḏīttā, not *mḏīntā, with the mṭalqānā over the nūn, assimilating with the taw).

The line can only occur above a letter ʾālep̄, hē, waw, yōḏ, lāmaḏ, mīm, nūn, ʿē or rēš (which comprise the mnemonic ܥܡ̈ܠܝ ܢܘܗܪܐ ʿamlay nūhrā, 'the works of light').

Classically, mṭalqānā was not used for silent letters that occurred at the end of a word (e.g. ܡܪܝ mār[ī], '[my] lord').

In Syriac romanization, some letters are altered and would feature diacritics and macrons to indicate long vowels, schwas and diphthongs.