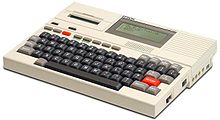

TRS-80 Model 100

[1] It features a keyboard and liquid-crystal display, in a battery-powered package roughly the size and shape of a notepad or large book.

The computer was sold through Radio Shack stores in the United States and Canada and affiliated dealers in other countries.

[5] The Model 100 was promoted as being able to run up to 20 hours and maintain memory up to 30 days on a set of four alkaline AA batteries.

[citation needed] The computer's available form of mass storage is the port for a cassette audiotape recorder, which is reportedly finicky and unreliable.

A Disk/Video Interface expansion box was released in 1984, with one single-sided double-density 180 KB 5-1/4 inch disk drive and a CRT video adapter.

[13] The ROM firmware-based system boots instantly, and the program that was running when the unit was powered off is ready to use immediately on power-up.

Cursor keys are used to navigate the menu and select one of the internal or added application programs, or any data file to be worked upon.

When introduced, the portability and simplicity of the Model 100 made it attractive to journalists,[16][17][18] who could type about 11 pages of text (if upgraded to the maximum of 32 KB RAM) and then transmit it for electronic editing and production using the built-in modem and TELCOM program.

[17] The computer is otherwise silent when it operates, except for the speaker, and runs for 20 hours on 4 readily available and easily replaceable AA batteries.

The Model 100 was also used for industrial applications and in science laboratories as a programming terminal for configuration of control systems and instruments.

Its compactness (ease of handling and small space requirements), low maintenance needs, lack of air vents (a plus for dusty or dirty environments), full complement of ports, and easy portability made it very well suited for these applications.

As with virtually all other contemporary home computers, users are able to create their own applications using the included BASIC programming language.

There are no built-in facilities for 8085 assembler programming, but the thoroughly-documented BASIC interpreter by Microsoft offered the clever coder tricks for accessing machine code subroutines.

These tricks usually involved packing the raw object code into strings or integer arrays, and would be familiar to veteran programmers for the older TRS-80 Models I and III.

This model resembled the IBM PC Convertible with a "clamshell" design and had a screen supporting a textual display of 80 x 25 characters and a graphical resolution of 640 x 200 pixels, with eight intensity levels achieved using a form of pulse-width modulation.

Both Convergent Technologies and MicroOffice released the WorkSlate and the RoadRunner respectively in late 1983, which similarly targeted mobile computing.

The Cambridge Z88 of 1987, developed by British inventor Sir Clive Sinclair, had greater expansion capacity due to its built-in cartridge slots.

The firmware contained a powerful application called Pipedream that was a spreadsheet that could also serve capably as a word processor and database.

The electronic word processing keyboards AlphaSmart Dana and the Quickpad Pro bear some resemblance to the physical format of the TRS-80 Model 100.

[34] The system's popularity with journalists, however, probably helped Radio Shack improve the company's poor reputation with the press and in the industry.

He concluded, "I'm not used to giving Radio Shack kudos, but the Model 100 is a brave, imaginative, useful addition to the realm of microcomputerdom" and "a leading contender for InfoWorld's Hardware Product of the Year for 1983",[35] an award which it indeed won.

[24] PC Magazine criticized the Model 100 display's viewing angle, but noted that the text editor automatically reflowed paragraphs unlike WordStar.

[38] Creative Computing said that the Model 100 was "the clear winner" in the category of notebook portables under $1000 for 1984, although cautioning that "the 8K version is practically useless".