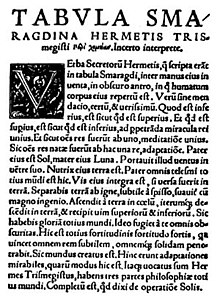

Emerald Tablet

[6] These Greek pseudepigraphal texts found receptions, translations and imitations in Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, and Middle Persian prior to the emergence of Islam and the Arab conquests in the 630s.

The oldest version is found as an appendix in a treatise believed to have been composed in the 9th century,[9] known as the Book of the Secret of Creation, Kitâb sirr al-Halîka in Arabic.

Balînûs, "master of talismans and wonders," enters a crypt beneath the statue of Hermes Trismegistus and finds the emerald tablet in the hands of a seated old man, along with a book.

The core of the work is primarily an alchemical treatise that introduces for the first time the idea that all metals are formed from sulfur and mercury, a fundamental theory of alchemy in the Middle Ages.

[13] It has long been debated whether it is an extraneous piece, solely cosmogonic in nature, or if it is an integral part of the rest of the work, in which case it has an alchemical significance from the outset.

[16] In antiquity, Greeks and Egyptians referred to various green-coloured minerals (green jasper and even green granite) as emerald, and in the Middle Ages, this also applied to objects made of coloured glass, such as the "Emerald Tablet" of the Visigothic kings [17] or the Sacro Catino of Genoa (a dish seized by the Crusaders during the sack of Caesarea in 1101, which was believed to have been offered by the Queen of Sheba to Solomon and used during the Last Supper).

[18] This version of the Emerald Tablet is also found in the Kitab Ustuqus al-Uss al-Thani (Elementary Book of the Foundation) attributed to the 8th-century alchemist Jâbir ibn Hayyân, known in Europe by the latinized name Geber.

This motif is frequently used in Renaissance prints and is the visual expression of the myth of the rediscovery of ancient knowledge—the transmission of this knowledge, in the form of hieroglyphic pictograms, allows it to escape the distortions of human and verbal interpretation.

[31] During the Renaissance, the idea that Hermes Trismegistus was the founder of alchemy gained prominence, and at the same time, the legend of the discovery evolved and intertwined with biblical accounts.

[33] It further evolves with Jérôme Torella in his book on astrology, Opus Praeclarum de imaginibus astrologicis (Valence, 1496), in which it is Alexander the Great who discovers a Tabula Zaradi in Hermes' tomb while travelling to the Oracle of Amun in Egypt.

This story is repeated by Michael Maier, physician and counselor to the "alchemical emperor" Rudolf II, in his symbola aureae mensae (Frankfurt, 1617), referring to a Liber de Secretis chymicis attributed to Albertus Magnus.

However, from the beginning of the 17th century onward, a number of authors challenge the attribution of the Emerald Tablet to Hermes Trismegistus and, through it, attack antiquity and the validity of alchemy.

By comparing the vocabulary used with that of the Corpus Hermeticum (which had been proven by Isaac Casaubon in 1614 to date only from the 2nd or 3rd century AD), he affirms that the Emerald Tablet is a forgery by a medieval alchemist.

As for the alchemical teaching of the Emerald Tablet, it is not limited to the philosopher's stone and the transmutation of metals but concerns "the deepest substance of each thing," the alchemists' quintessence.

From another perspective, Wilhelm Christoph Kriegsmann [de] publishes in 1657 a commentary in which he tries to demonstrate, using the linguistic methods of the time, that the Emerald Tablet was not originally written in Egyptian but in Phoenician.

He continues his studies of ancient texts and in 1684 argues that Hermes Trismegistus is not the Egyptian Thoth but the Taaut of the Phoenicians, who is also the founder of the Germanic people under the name of the god Tuisto, mentioned by Tacitus.

[36] In the meantime, Kircher's conclusions are debated by the Danish alchemist Ole Borch in his De ortu et progressu Chemiae (1668), in which he attempts to separate the hermetic texts between the late writings and those truly attributable to the ancient Egyptian Hermes, among which he inclines to classify the Emerald Tablet.

The discussions continue, and the treatises of Ole Borch and Kriegsmann are reprinted in the compilation Bibliotheca Chemica Curiosa (1702) by the Swiss physician Jean-Jacques Manget.

Although the Emerald Tablet is still translated and commented upon by Isaac Newton,[37] alchemy gradually loses all scientific credibility during the 18th century with the advent of modern chemistry and the work of Lavoisier.

For example, in 1733, according to the alchemist Ehrd de Naxagoras (Supplementum Aurei Velleris), a "precious emerald plate" engraved with inscriptions and the symbol was made upon Hermes' death and found in the valley of Ebron by a woman named Zora.

[34] This emblem is placed within the mysterious tradition of Egyptian hieroglyphs and the idea of Platonists and alchemists during the Renaissance that the "deepest secrets of nature could only be expressed appropriately through an obscure and veiled mode of representation".

This is the case with the mage Éliphas Lévi: "Nothing surpasses and nothing equals as a summary of all the doctrines of the old world the few sentences engraved on a precious stone by Hermes and known as the 'emerald tablet'... it is all of magic on a single page.".

[42] It also applies to the "curious figure"[43] of the German Gottlieb Latz, who self-published a monumental work Die Alchemie in 1869,[44] as well as the theosophist Helena Blavatsky[45] and the perennialist Titus Burckhardt.

[46] At the beginning of the 20th century, alchemical thought resonated with the surrealists,[47] and André Breton incorporated the main axiom of the Emerald Tablet into the Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1930): "Everything leads us to believe that there exists a certain point of the spirit from which life and death, the real and the imaginary, the past and the future, the communicable and the incommunicable, the high and the low, cease to be perceived as contradictory.

[50] Like most other works attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, the Emerald Tablet is very hard to date with any precision, but generally belongs to the late antique period (between c. 200 and c. 800).

[55] Slightly different versions of the Emerald Tablet also appear in the Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss al-thānī (The Second Book of the Element of the Foundation, c. 850–950) attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan,[56] in the longer version of the Sirr al-asrār (The Secret of Secrets, a tenth-century compilation of earlier works that was falsely attributed to Aristotle),[57] and in the Egyptian alchemist Muhammed ibn Umail al-Tamimi's (ca.

Vos ergo, prestigiorum filii, prodigiorum opifices, discretione perfecti, si terra fiat, eam ex igne subtili, qui omnem grossitudinem et quod hebes est antecellit, spatiosibus, et prudenter et sapientie industria, educite.

Unde omnis ex eodem illuminatur obscuritas, cuius videlicet potentia quicquid subtile est transcendit et rem grossam, totum, ingreditur.

Sic ergo dominatur inferioribus et superioribus et tu dominaberis sursum et deorsum, tecum enim est lux luminum, et propter hoc fugient a te omnes tenebre.

[77] A line from the Latin version, "Sic mundus creatus est" (So was the world created), plays a prominent thematic role in the series and is the title of the sixth episode of the first season.