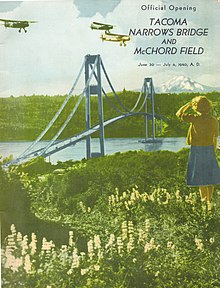

Tacoma Narrows Bridge (1940)

From the time the deck was built, it began to move vertically in windy conditions, so construction workers nicknamed the bridge "Galloping Gertie".

The violent swaying and eventual collapse resulted in the death of a cocker spaniel named "Tubby",[3] as well as inflicting injuries on people fleeing the disintegrating bridge or attempting to rescue the stranded dog.

In many physics textbooks, the event is presented as an example of elementary forced mechanical resonance, but it was more complicated in reality; the bridge collapsed because moderate winds produced aeroelastic flutter that was self-exciting and unbounded: for any constant sustained wind speed above about 35 mph (56 km/h), the amplitude of the (torsional) flutter oscillation would continuously increase, with a negative damping factor, i.e., a reinforcing effect, opposite to damping.

At the 1938 meeting of the structural division of the American Society of Civil Engineers, during the construction of the bridge, with its designer in the audience, Steinman predicted its failure.

[8] From the start, financing of the bridge was a problem: Revenue from the proposed tolls would not be enough to cover construction costs; another expense was buying out the ferry contract from a private firm running services on the Narrows at the time.

Preliminary construction plans by the Washington Department of Highways had called for a set of 25-foot-deep (7.6 m) trusses to sit beneath the roadway and stiffen it.

A mild to moderate wind could cause alternate halves of the centre span to visibly rise and fall several feet over four- to five-second intervals.

Towards the last, I risked rising to my feet and running a few yards at a time ... Safely back at the toll plaza, I saw the bridge in its final collapse and saw my car plunge into the Narrows.

Howard Clifford, a photographer for the Tacoma News Tribune, walked onto the bridge to try to save Tubby, but was forced to turn back when the span began to break apart in the center.

Coatsworth received $814.40 (equivalent to $17,700 today)[15] in reimbursement from the Washington State Toll Bridge Authority for his car and its contents, including Tubby the cocker spaniel.

[18] In 1998, The Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.

[20] As a result, most copies in circulation also show the bridge oscillating approximately 50% faster than real time, due to an assumption during conversion that the film was shot at 24 frames per second rather than the actual 16 fps.

[22] Theodore von Kármán, the director of the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory and a world-renowned aerodynamicist, was a member of the board of inquiry into the collapse.

The agent, Hallett R. French, who represented the Merchant's Fire Assurance Company, was charged and tried for grand larceny for withholding the premiums for $800,000 worth of insurance (equivalent to $17.4 million today).

[25] On November 28, 1940, the U.S. Navy's Hydrographic Office reported that the remains of the bridge were located at geographical coordinates 47°16′N 122°33′W / 47.267°N 122.550°W / 47.267; -122.550, at a depth of 180 feet (55 meters).

Without drawing any definitive conclusions, the commission explored three possible failure causes: The original Tacoma Narrows Bridge was the first to be built with girders of carbon steel anchored in concrete blocks; preceding designs typically had open lattice beam trusses underneath the roadbed.

[27] Shortly after construction finished at the end of June (opened to traffic on July 1, 1940), it was discovered that the bridge would sway and buckle dangerously in relatively mild windy conditions that are common for the area, and worse during severe winds.

The bridge's spectacular destruction is often used as an object lesson in the necessity to consider both aerodynamics and resonance effects in civil and structural engineering.

The solution of such ordinary differential equation as a function of time t represents the displacement response of the system (given appropriate initial conditions).

[33] Billah and Scanlan[33] state that Lee Edson in his biography of Theodore von Kármán[34] is a source of misinformation: "The culprit in the Tacoma disaster was the Karman vortex street."

However, the Federal Works Administration report of the investigation, of which von Kármán was part, concluded that It is very improbable that the resonance with alternating vortices plays an important role in the oscillations of suspension bridges.

The user's guide for the current American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT) DVD states the bridge collapse "was not a case of resonance."

Bernard Feldman likewise concluded in a 2003 article for the Physics Teacher that for the torsional oscillation mode, there was "no resonance behavior in the amplitude as a function of the wind velocity."

An important source for both the AAPT user's guide and for Feldman was a 1991 American Journal of Physics article by K. Yusuf Billah and Robert Scanlan.

The fluid dynamics behind that amplification is complicated, but one key element, as described by physicists Daniel Green and William Unruh, is the creation of large-scale vortices above and below the roadway, or deck, of the bridge.

For example, when the storm reached Illinois, the headline on the front page of the Chicago Tribune included the words "Heaviest winds in this century smash at city."

[37] The cable anchorages, tower pedestals and most of the remaining substructure were relatively undamaged in the collapse, and were reused during construction of the replacement span that opened in 1950.

The towers, which supported the main cables and road deck, suffered major damage at their bases from being deflected 12 feet (3.7 m) towards shore as a result of the collapse of the mainspan and the sagging of the sidespans.

The underwater remains of the highway deck of the old suspension bridge act as a large artificial reef, and these are listed on the National Register of Historic Places with reference number 92001068.

Because of shortages in materials and labor as a result of the involvement of the United States in World War II, it took 10 years before a replacement bridge was opened to traffic.

(19.1 MB video, 02:30).