Taft–Hartley Act

Though it was enacted by the Republican-controlled 80th Congress, the law received significant support from congressional Democrats, many of whom joined with their Republican colleagues in voting to override Truman's veto.

[2] Many of the newly elected congressmen were strongly conservative and sought to overturn or roll back New Deal legislation such as the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which had established the right of workers to join unions, bargain collectively, and engage in strikes.

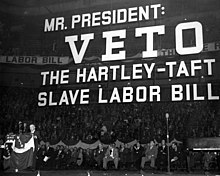

[5] After spending several days considering how to respond to the bill, President Truman vetoed Taft–Hartley with a strong message to Congress,[6] calling the act a "dangerous intrusion on free speech.

Furthermore, the executive branch of the federal government could obtain legal strikebreaking injunctions if an impending or current strike imperiled the national health or safety.

According to First Amendment scholar Floyd Abrams, the act "was the first law barring unions and corporations from making independent expenditures in support of or [in] opposition to federal candidates".

[citation needed] The amendments required unions and employers to give 80 days' notice to each other and to certain state and federal mediation bodies before they may undertake strikes or other forms of economic action in pursuit of a new collective bargaining agreement; it did not, on the other hand, impose any "cooling-off period" after a contract expired.

§ 176, also authorized a president to intervene in strikes or lockouts, under certain circumstances, by seeking a court order compelling companies and unions to attempt to continue to negotiate.

[13] Under this section, if the president determines that an actual or threatened lockout affects all or a substantial part of an industry engaged in interstate or foreign "trade, commerce, transportation, transmission, or communication" and that the occurrence or continuation of a strike or lockout would "imperil the national health or safety," the President may empanel a board of inquiry to review the issues and issue a report.

[13] If a court enters an injunction, then a strike by workers or a lockout by employers is suspended for an 80-day period; employees must return to work while management and unions must "make every effort to adjust and settle their differences"[13][14] with the assistance of the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service.

[14] In 2002, President George W. Bush invoked the law in connection with the employer lockout of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union during negotiations with West Coast shipping and stevedoring companies.

The amendments gave the general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board discretionary power to seek injunctions against either employers or unions that violated the act.

[21] The Congress that passed the Taft–Hartley Amendments considered repealing the Norris–La Guardia Act to the extent necessary to permit courts to issue injunctions against strikes violating a no-strike clause, but chose not to do so.

Union leaders in the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) vigorously campaigned for Truman in the 1948 election based upon a (never fulfilled) promise to repeal Taft–Hartley.

[22] Truman won, but a union-backed effort in Ohio to defeat Taft in 1950 failed in what one author described as "a shattering demonstration of labor's political weaknesses".