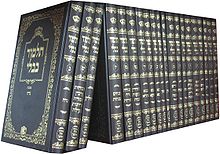

Talmud

[15] The Jerusalem Talmud was a written codification of oral tradition that had been circulating for centuries[16] and represents a compilation of scholastic teachings and analyses on the Mishnah (especially those concerning agricultural laws) found across regional centres of the Land of Israel now known as the Academies in Galilee (principally those of Tiberias, Sepphoris, and Caesarea).

[22] During this time, the most important of the Jewish centres in Mesopotamia, a region called "Babylonia" in Jewish sources (see Talmudic academies in Babylonia) and later known as Iraq, were Nehardea, Nisibis (modern Nusaybin), Mahoza (al-Mada'in, just to the south of what is now Baghdad), Pumbedita (near present-day al Anbar Governorate), and the Sura Academy, probably located about 60 km (37 mi) south of Baghdad.

Each tractate is divided into chapters (perakim; singular: perek), 517 in total, that are both numbered according to the Hebrew alphabet and given names, usually using the first one or two words in the first Mishnah.

[38] In addition, the Gemara contains a wide range of narratives, homiletical or exegetical passages, sayings, and other non-legal content, termed aggadah.

The work is largely in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, although quotations in the Gemara of the Mishnah, the Baraitas and Tanakh appear in Mishnaic or Biblical Hebrew.

[24] Seder Olam Zutta records that "in 811 SE (500 CE) Ravina the End of Instruction died, and the Talmud was stopped", and the same text is found in Codex Gaster 83.

[49] Another medieval chronicle records that "On Wednesday, 13 Kislev, 811 SE (500 CE), Ravina the End of Instruction son of Rav Huna died, and the Talmud stopped.

[55] Recently, it has been extensively argued that Talmud is an expression and product of Sasanian culture,[56][57][58] as well as other Greek-Roman, Middle Persian, and Syriac sources up to the same period of time.

Early commentators such as Isaac Alfasi (North Africa, 1013–1103) attempted to extract and determine the binding legal opinions from the vast corpus of the Talmud.

His son, Zemah ben Paltoi paraphrased and explained the passages which he quoted; and he composed, as an aid to the study of the Talmud, a lexicon which Abraham Zacuto consulted in the fifteenth century.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a genre of rabbinic literature emerged surrounding Rashi's commentary, with the purpose of supplementing it and addressing internal contradictions via the technique of pilpul.

Commentaries (ḥiddushim) by Joseph ibn Migash on two tractates, Bava Batra and Shevuot, based on Ḥananel and Alfasi, also survive, as does a compilation by Zechariah Aghmati called Sefer ha-Ner.

This kind of study reached its height in the 16th and 17th centuries when expertise in pilpulistic analysis was considered an art form and became a goal in and of itself within the yeshivot of Poland and Lithuania.

[73] This method was first recorded, though without explicit reference to Aristotle, by Isaac Campanton (d. Spain, 1463) in his Darkhei ha-Talmud ("The Ways of the Talmud"),[74] and is also found in the works of Moses Chaim Luzzatto.

Brisker method involves a reductionistic analysis of rabbinic arguments within the Talmud or among the Rishonim, explaining the differing opinions by placing them within a categorical structure.

The convention of referencing by daf is relatively recent and dates from the early Talmud printings of the 17th century, though the actual pagination goes back to the Bomberg edition.

Between 2007 and 2009, Yong-soo Hyun of the Shema Yisrael Educational Institute published a 6-volume edition of the Korean Talmud, bringing together material from a variety of Tokayer's earlier books.

[173][174] At the very time that the Babylonian savoraim put the finishing touches to the redaction of the Talmud, the emperor Justinian issued his edict against deuterosis (doubling, repetition) of the Hebrew Bible.

There is a quoted Talmudic passage, for example, where a person named Yeshu who some people have claimed is Jesus of Nazareth is sent to Gehenna to be boiled in excrement for eternity.

[179] The Talmud was likewise the subject of the Disputation of Barcelona in 1263 between Nahmanides and Christian converts in which they argued if Jesus was the messiah prophesized in Judaism, Pablo Christiani.

[180][181] At the Disputation of Tortosa in 1413, Geronimo de Santa Fé brought forward a number of accusations, including the fateful assertion that the condemnations of "pagans", "heathens", and "apostates" found in the Talmud were, in reality, veiled references to Christians.

[181] Both Pablo Christiani and Geronimo de Santa Fé, in addition to criticizing the Talmud, also regarded it as a source of authentic traditions, some of which could be used as arguments in favor of Christianity.

[182] In 1415, Antipope Benedict XIII, who had convened the Tortosa disputation, issued a papal bull (which was destined, however, to remain inoperative) forbidding the Jews to read the Talmud, and ordering the destruction of all copies of it.

The result of these accusations was a struggle in which the emperor and the pope acted as judges, the advocate of the Jews being Johann Reuchlin, who was opposed by the obscurantists; and this controversy, which was carried on for the most part by means of pamphlets, became in the eyes of some a precursor of the Reformation.

[181][183] An unexpected result of this affair was the complete printed edition of the Babylonian Talmud issued in 1520 by Daniel Bomberg at Venice, under the protection of a papal privilege.

On the New Year, Rosh Hashanah (September 9, 1553) the copies of the Talmud confiscated in compliance with a decree of the Inquisition were burned at Rome, in Campo dei Fiori (auto de fé).

After an attack on the Talmud took place in Poland (in what is now Ukrainian territory) in 1757, when Bishop Dembowski, at the instigation of the Frankists, convened a public disputation at Kamieniec Podolski, and ordered all copies of the work found in his bishopric to be confiscated and burned.

[192] In 1830, during a debate in the French Chamber of Peers regarding state recognition of the Jewish faith, Admiral Verhuell declared himself unable to forgive the Jews whom he had met during his travels throughout the world either for their refusal to recognize Jesus as the Messiah or for their possession of the Talmud.

[198] Historians Will and Ariel Durant noted a lack of consistency between the many authors of the Talmud, with some tractates in the wrong order, or subjects dropped and resumed without reason.

[203] Gil Student, Book Editor of the Orthodox Union's Jewish Action magazine, states that many attacks on the Talmud are merely recycling discredited material that originated in the 13th-century disputations, particularly from Raymond Marti and Nicholas Donin, and that the criticisms are based on quotations taken out of context and are sometimes entirely fabricated.