Talmudic academies in Babylonia

It is neither geopolitically, nor geographically identical with the ancient empires of Babylonia, since the Jewish focus of interest has to do with the Jewish religious academies, which were mainly situated in an area between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and primarily between Pumbedita (modern Fallujah, a town west of Baghdad), and Sura, a town farther south down the Euphrates.

For the Jews of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, the yeshivot of Babylonia served much the same function as the ancient Sanhedrin, i.e., as a council of Jewish religious authorities.

The academies were founded in pre-Islamic Babylonia under the Zoroastrian Sasanians and were located not far from the Sassanid capital of Ctesiphon, which at that time was the largest city in the world.

The Geonim[4] (Hebrew: גאונים) were the presidents of the two great rabbinical colleges of Sura and Pumbedita, and were the generally accepted spiritual leaders of the worldwide Jewish community in the early Middle Ages, in contrast to the Resh Galuta (Exilarch) who wielded secular authority over the Jews in Islamic lands.

Sura and Pumbedita were considered the only important seats of learning: their heads and sages were the undisputed authorities, whose decisions were sought from all sides and were accepted wherever Jewish communal life existed.

This region was known to contemporaries as the Sasanian province of Asōristān until the Muslim conquest in 637,[5][6] after which it becomes known in Arabic as Sawad or al-'Irāq al-'Arabi ("Arabian Irāq").

The Jewish sources only concentrate on the area between the main two academies, Pumbedita (modern Fallujah; west of Baghdad) in the north, and Sura in the south.

In the period before Hadrian, Rabbi Akiva, on his arrival at Nehardea on a mission from the Sanhedrin, entered into a discussion with a resident scholar on a point of matrimonial law (Mishnah Yeb., end).

Among those that helped to restore Jewish learning, after Hadrian, was the Babylonian scholar Nathan, a member of the family of the exilarch, who continued his activity even under Judah the Prince.

Under these masters the study of the Law attained a notable development, to which certain Judean-Palestinian scholars, driven from their own homes by the persecutions of Roman tyranny, contributed no inconsiderable share.

In his method of teaching may be discerned the first traces of an attempt to edit the enormous mass of material that ultimately formed the Babylonian Talmud.

The unusual length of Ashi's activity, his undeniable high standing, his learning, as well as the favorable circumstances of the day, were all of potent influence in furthering the task he undertook; namely, that of sifting and collecting the material accumulated for two centuries by the Babylonian academies.

The final editing of the literary work which this labour produced did not, it is true, take place until somewhat later; but tradition rightly names Ashi as the originator of the Babylonian Talmud.

His work was continued and perfected, and probably reduced to writing, by succeeding heads of the Sura Academy, who preserved the fruit of his labors in those sad times of persecution which, shortly after his death, were the lot of the Jews of Babylonia.

These misfortunes were undoubtedly the immediate cause of the publication of the Talmud as a complete work; and from the Academy of Sura was issued that unique literary effort which was destined to occupy such an extraordinary position in Judaism.

Sura and Pumbedita were considered the only important seats of learning: their heads and sages were the undisputed authorities, whose decisions were sought from all sides and were accepted wherever Jewish communal life existed.

"[9] The periods of Jewish history immediately following the close of the Talmud are designated according to the titles of the teachers at Sura and Pumbedita; the time of the Geonim and that of the Savoraim.

In point of fact, both titles are only conventionally and indifferently applied; the bearers of them are heads of either of the two academies of Sura and Pumbedita and, in that capacity, successors of the Amoraim.

Pumbedita, on the other hand, may boast that two of its teachers, Sherira and his son Hai Gaon (died 1038), terminated in most glorious fashion the age of the Geonim and with it the activities of the Babylonian academies.

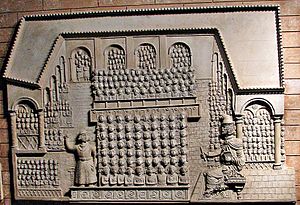

An account dating from the 10th century, describing the order of procedure and of the differences in rank at the kallah, contains details that refer only to the period of the Geonim; but much of it extends as far back as the time of the Amoraim.

They sit in the following order of rank: Immediately next to the president is the first row, consisting of ten men; seven of these are rashe kallah; three of them are called 'ḥaberim' [associates].

The head adds his own exposition, and when everything has been made clear one of those in the first row arises and delivers an address, intended for the whole assembly, summing up the arguments on the theme they have been considering.