Somerton Man

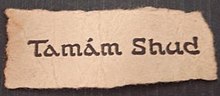

The case is also known after the Persian phrase tamám shud (تمام شد),[note 1] meaning "It is over" or "It is finished", which was printed on a scrap of paper found months later in the fob pocket of the man's trousers.

Public interest in the case remains significant for several reasons: the death occurred at a time of heightened international tensions following the beginning of the Cold War; the apparent involvement of a secret code; the possible use of an undetectable poison; and the inability or unwillingness of authorities to identify the dead man.

[5] To do this, Fitzpatrick and Abbott started with a match in a DNA database (a "genetic cousin" of the Somerton Man) and then traced his family tree until they found someone who fit the profile they were looking for.

[6] On 1 December 1948 at 6:30 am, the police were contacted after the body of a man was discovered by a couple on Somerton Park beach near Glenelg, about 11 km (7 mi) southwest of Adelaide, South Australia.

[9][10] A search of his pockets revealed an unused second-class rail ticket from Adelaide to Henley Beach; a bus ticket from the city that may not have been used; a narrow aluminium comb that had been manufactured in the US; a half-empty packet of Juicy Fruit chewing gum; an Army Club cigarette packet which contained seven cigarettes of a different brand, Kensitas; and a quarter-full box of Bryant & May matches.

[17] He was: 180 centimetres (5 ft 11 in) tall, with grey eyes, fair to ginger-coloured hair,[18] slightly grey around the temples,[8] with broad shoulders and a narrow waist, hands and nails that showed no signs of manual labour, big and little toes that met in a wedge shape, like those of a dancer or someone who wore boots with pointed toes; and pronounced high calf muscles consistent with people who regularly wore boots or shoes with high heels or performed ballet.

An inquest into the man's death, conducted by coroner Thomas Erskine Cleland, commenced a few days following the discovery of the body but was adjourned until 17 June 1949.

[38] Public library officials called in to translate the text identified it as a phrase meaning "ended" or "finished" found on the last page of Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.

In 1949, Jessica Thomson requested that police not keep a permanent record of her name or release her details to third parties, as it would be embarrassing and harmful to her reputation to be linked to such a case.

[13] In news media, books and other discussions of the case, Thomson was frequently referred to by various pseudonyms, including the nickname "Jestyn" and names such as "Teresa Johnson née Powell".

[60] In the front of the copy of Rubaiyat that was given to Boxall, Jessica Harkness had signed herself "JEstyn" [sic] and written out verse 70: Indeed, indeed, Repentance oft before I swore—but was I sober when I swore?

[62][63] That same day, The News published a photograph of the dead man on its front page,[64] leading to additional calls from members of the public about his possible identity.

[34] On 6 June 1949, the body of two-year-old Clive Mangnoson was found in a sack in the Largs Bay sand hills, about 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of Somerton Park.

[78] Following the death, the boy's mother, Roma Mangnoson, reported having been threatened by a masked man who, while driving a battered cream car, almost ran her down outside her home in Cheapside Street, Largs North.

Police suspect the calls may be a hoax and the caller may be the same person who also terrorised a woman in a nearby suburb who had recently lost her husband in tragic circumstances.

[47] In 1994, John Harber Phillips, Chief Justice of Victoria and Chairman of the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, reviewed the case to determine the cause of death and concluded that, "There seems little doubt it was digitalis.

"[85] Phillips supported his conclusion by pointing out that the organs were engorged, consistent with digitalis, the lack of evidence of natural disease and "the absence of anything seen macroscopically which could account for the death".

At least two sites relatively close to Adelaide were of interest to spies: the Radium Hill uranium mine and the Woomera Test Range, an Anglo-Australian military research facility.

In a 1978 television interview Stuart Littlemore asks: "Mr Boxall, you had been working, hadn't you, in an intelligence unit, before you met this young woman, Jessica Harkness.

The card, a document issued in the United States to foreign seamen during World War I, was given to Henneberg in October 2011 for comparison of the ID photograph to that of the Somerton man.

[52] She suggested that her mother and the Somerton man may both have been spies, noting that Jessica Thomson taught English to migrants, was interested in communism, and could speak Russian, although she would not disclose to Kate where she had learned it or why.

[52] Abbott also subsequently wrote to Rau in support of the Egans, saying that exhumation for DNA testing would be consistent with the federal government's policy of identifying soldiers in war graves, to bring closure to their families.

Anne Coxon, the Assistant Director of Operations at Forensic Science South Australia, said: "The technology available to us now is clearly light years ahead of the techniques available when this body was discovered in the late 1940s," and that tests would use "every method at our disposal to try and bring closure to this enduring mystery".

[100] In March 2009, a University of Adelaide team led by Professor Derek Abbott began an attempt to solve the case through cracking the code and proposing to exhume the body to test for DNA.

[48] An investigation had shown that the Somerton man's autopsy reports of 1948 and 1949 are now missing and the Barr Smith Library's collection of Cleland's notes do not contain anything on the case.

[102] In May 2009, Abbott consulted with dental experts who concluded that the Somerton Man had hypodontia (a rare genetic disorder) of both lateral incisors, a feature present in only 2% of the general population.

In June 2010, Abbott obtained a photograph of Jessica Thomson's eldest son Robin, which clearly showed that he – like the unknown man – had not only a larger cymba than cavum but also hypodontia.

[111][112] On 26 July 2022, Abbott announced that he and genealogist Colleen Fitzpatrick had determined that the man was Carl "Charles" Webb, an electrical engineer and instrument maker born on 16 November 1905, in Footscray, a suburb of Melbourne.

[113] Abbott claimed his DNA identification from strands of hair found in the plaster death mask made by South Australian Police in the late 1940s.

Dorothy described Carl as solitary, having few friends, living a quiet life and being in bed by 7 p.m. each night, but also moody, violent and threatening, especially when facing defeat even over relatively trivial matters.